A grey wolf, some pigeons, and a jet plane

Is painting still capable of telling any narrative any more? Past the silent monochrome pictures, isn’t a story told by a painting an anachronism? I guess, it is. But on the other hand, even a lonely light-blue, or an explosive red, do happen to be talkative. There are still painters who are willing to tell stories, those real ones and those somewhat alien ones. They would paint women, animals, or flowers. And, the sky with a plane in it, being watched by a grey wolf.

Jacek Łydżba is one among those story-telling painters. Although his stories are simple, it is nice to hear them. Most of them have been spotted in the real life. They take place against a homogeneous background: an intense light-blue or bright yellow or green. These colours become the basis for a narration being, in most cases, one- or two-threaded: be it a thoughtful policewoman, an aviator watching pigeons, a couple of marching soldiers, or, a wolf ‘talking’ to an aeroplane. These stories appear warm and bright. For instance, a wolf and a bird are involved in a friendly chat, their ‘common ground’ being yellow colour. An ambience of pleasantness is also present around the yellow-and-brown story on boys of a boys’ band, a collective portrait of musicians. Sometimes, however, this carefree aura is broken with a shade of melancholy. This is how a woman’s eyes see things in A face in red, with a light-blue ingredient. Some of the tales contain, however, a hidden ‘something beyond’ the mere sorrowfulness or melancholy; a threat may namely be sensed. For, though the three planes form a figure in the sky resembling a birds’ vee formation, this is definitely not a story on one’s safety.

In Jacek Łydżba’s earlier works, stories were predominating on women, dressed in a Greekish manner, or winged like angels, or, at times, more of our-contemporary ones, such as roller-skating or cycling. Some flowers and some pigeons were reappearing there as well. A womanish/bird-like sweetness was being broken by ‘manly’ stories, on the indispensable planes or (not so often) road vehicles. The last pictures also testify to an intensifying interest in the ‘lives of those wearing uniforms’, as rendered uniform(ed) by virtue of dress: so, there’s the reflective policewoman story; a story on soldiers marching in a formation in front of the Warsaw’s Unknown Soldier’s Tomb: marching across the painting’s yellow space as if they were dancing a war dance. However, as opposed to the aircraft vee formation, these marching figures appear closer to a boy’s playing with his lead toy-soldiers rather than to any true wartime story. Through these, Jacek tells us in the first place of what is most important for the painter: i.e. arrangements of shapes and colours, giving a temper to the figures and motives being presented. The story is also about how a single element may come closer to an ornament; on a repetitive nature of systems; on the rhythm which has once propelled and set art in motion.

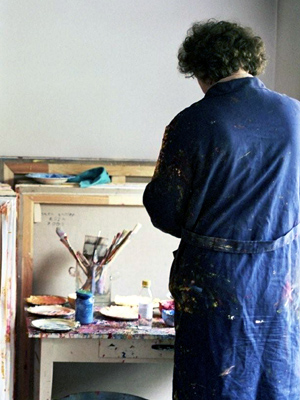

How come Jacek Łydżba is so much keen on story-telling? And, why should such type(s) of characters ever appear in these pictures? He simply speaks about anything surrounding him. That is, his closest relatives, acquaintances, or people he has met. He confirms that the ‘Grand History’ has always been a focus of his interest: important battles, how they proceeded, and their ‘innate’ heroism. Whilst still in his early childhood, he would put together aircraft models; then, they became the ‘characters’ proper of his ‘adult’ paintings. The form of his painting has also been influenced by his Arts Academy studies, Poster Workshop. This is why his pictures are usually stories with a central motif, impressed, as it were, from a template, or taken from a children’s colouring book. But it is there that any features common with poster end. Jacek’s painting technique is anything but ‘flat’: on the contrary, he spreads the paint in thick layers, in a fleshy manner, losing contours within the matter of paint. This is closer to a sculptor’s work, or relief maker’s. Colour too escapes any bonds with poster; indeed, it proves intense, but links shades of one colour, is spread in layers, glazed. In Jacek’s recent paintings, the composition is gaining in dynamism as it becomes diagonal, ‘open-ended’.

A place of import in Jacek Łydżba’s activities is taken by templates. Cut-out motifs may be a source of inspiration for paintings, but they exist as self-contained elements as well. They are impressed on cardboard sheets, gained sometimes from some boxes, bearing traces of its primary function in the form of various markings, such as a company’s brand or logo. Jacek creates funny contexts with template-based, painted-a-little motifs, such as a graceful figure of young lady right next to a ‘recyclable matter’ sign.

As is thus apparent, story-telling through painting is possible; building simple stories we are willing to listen to. Also of those sweet and banal ones. Even in those can we seek for ‘the other bottom’ indeed. Each piece of painting, through its form and colour, suggests what it really is, and what is there at its sources. Life is always somewhere there, even whenever a painting appears only a surface covered with abstract colours.