The sentimental side of the world of imagination

When someone stands in front of a mirror, they usually concentrate on their own reflection, while the rest - the background - escapes their attention. We see a lonely figure extracted from the blurred reality behind its back. The effect is enhanced if we look into a patina-covered mirror in the door of an old wardrobe. The stained surface no longer reflects the objects behind the standing person’s back, but a mysterious, rough space; against such a background our form, even though apparently well-known and familiar, seems to belong to the world on the other side of the looking-glass rather than to everyday reality.

If we allow the poetry of the old mirror to seduce us, it may happen that on the other side we will come across the figures which Jacek Lydzba paints in his pictures. His characters are extracted form context like a man in front of a mirror, shown against a background of shimmering, changing, vague contours of things reflected in old, mouldy mirrors. If , however, we try to reconstruct that context, it will turn out that they belong to a very close, although not always accessible and not to everyone, sentimental side of the world of imagination: the part of the world that is usually inhabited by childhood memories.

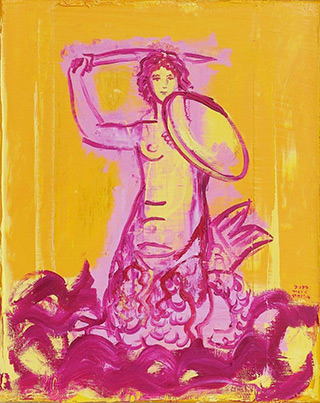

In Lydzba’s paintings emotional snapshots from his personal “Land of Gentleness” are superimposed on images of a little town from la Belle Epoque. A carefree atmosphere, to which adults nod their heads with patient understanding, childish fascination with the world, and the embarrassing intensity of emotion characteristic of youth, known to both the artist and his audience form their own experience, blend with the myth of the safe and orderly reality of grandfathers-when-they-were-little-boys. The “local motherland” of images always left behind after extreme admiration, delight of fear, translates in Lydzba’s work into pictures from old albums, a vision of provincial happiness in short trousers, or with a lace bow in its hair. A baroque angel of rather rustic parentage flies off the side altar, holding in his hand not a white lily of purity any longer, but a flower red as the first love of a spotty sixteen-year-old. But Lydzba’s heroes, even though at home in the world of emotions and sentiments which we prefer to attribute to children, speak the language of adults.

Aeroplanes as mighty as dinosaurs, a golden-haired boy riding a lion, ladies lovely as Helen in Offenbach’s operetta and girls dressed in their First Communion dresses are combined with rough form and a thoroughly modern aesthetic. The artist, although he relates to the immaterial world of memories reflected in the sentimental mirror of the small town of imagination, uses form to emphasize the materiality of images and their absolutely un-sentimental corporality. Fleeting memories, which we rightly suspect of false innocence, have been caught in the trap of greasy paint and thick, saturated, sometimes even vivid colours. It is thanks to such dissonances and the hardness of Lydzba’s painting style that the sentimental motifs still move and amuse us, even though it might seem that they should have long been buried by kitsch.