Katarzyna’s Memorial Book

They walk towards me only through the viburnums,

through thorns, through the blueberries

the dead, friends, and loved ones.

They walk towards me only through the rustling,

entangled between breathless whirlwinds:

‘You’re here?! Oh, what weather...’

A kind of symbolic and almost unreal Jewish town, probably located somewhere in eastern Europe, appears in the paintings. It could be Marc Chagall’s Liozna, Bruno Schulz’s Drohobych, or even Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Leoncin. However, I know that this is Szczebrzeszyn, where Katarzyna Karpowicz’s father, Sławomir, was born; a town where the artist spent many a holiday painting in the garden of her family home.

Just before the outbreak of the Second World War, 3,200 Jews lived in Szczebrzeszyn, equalling forty-three per cent of its total population. Although they were not in the majority, the town is sometimes considered a shtetl – this is how Philip Bibel, for example, writes about it in his memoir Tales of the Shtetl. The Jews there called their city Shebreshin in Yiddish (שצ’בז’שין). The wealthy and assimilated lived in tenement houses on Zamojska Street, while the poor nested in hovels in the area known as ‘Zatyły’. A Renaissance synagogue (now a community centre) stood on Sądowa Street and a mikvah building on Targowa Street. The hill was home to one of the oldest cemeteries in the former Republic – two thousand matzevot survived it, including some from the 16th century. There were also prayer houses, Jewish schools, and a library. Plays were staged by an amateur theatre club, political parties and youth organisations were active, and Yiddish newspapers were subscribed to.

The end of Shebreshin began on 13 September 1939, when German troops occupied the town. Ironically, it was also the date of Rosh Hashanah, a holiday commemorating the creation of the world and reminding us of God’s judgement. The first day of the Jewish calendar, from which the days – this time the last days – were counted. Persecution, starvation, murder, looting, and exile to forced labour camps began almost immediately. The synagogue and historic wooden houses were burnt down and the Jewish quarter in Zatyły was destroyed. The Polish neighbours watched impassively and even took the opportunity to enrich themselves. A poignant testimony to the Shebreshin Holocaust is the detailed and indeed heartless diary of Zygmunt Klukowski, director of the local hospital, in which the Jews appear as an anonymous mass subordinated to the legal acts of the occupying power (with no lack of anti-Semitic prejudice). The end came on 8 August 1942, when the round-ups began. Around 2,000 people were herded to the railway station in Brody, where a train with 55 wagons awaited them – they were sent to the transit camp in Izbica and then to the gas chambers of Belzec. The next transport of 934 people took place on 21 October. Those who remained in the town were murdered in the Shebreshin Jewish cemetery: the disrobed people had to enter deep pits where they were killed with shots to the back of the head; layers of bodies were piled up. Some escaped into the nearby forests, but most were caught by the Germans and their Polish helpers tempted by rewards of sugar and vodka. The victims’ homes were ransacked. Alina Skibińska writes in the book Night Without End: The Fate of Jews in German-Occupied Poland, edited by Barbara Engelking and Jan Grabowski: ‘After some time, a group of six enterprising local “entrepreneurs” opened a shop on Frampolska Street, selling “post-Jewish clothes”. Local Poles took up residence in some of the houses left behind by the murdered, others were demolished and still others collapsed on their own’.

Forty-three per cent. Almost half of the city, which disappeared and then was annihilated once more – by being wiped from memory. At lectures, I always ask students how many synagogues and Jewish prayer houses there were in Krakow before the war. They call out numbers – 15, 20, 30. When I display the list of 119 sites (including the Lev Tov synagogue at 20 St Gertrude Street (where my mum – the Barbara in the artist’s portraits – was born), there is a long silence However, memory is returning, not just in academic publications, museums being opened, monuments being restored and Jewish cemeteries being cleaned up, but also in artistic projects. This includes Rafał Betlejewski’s happening I Miss You, Jew, which in 2010 painted the title words on buildings in Polish cities and encouraged passers-by to take photos in front of them and published Polish memories of former Jewish neighbours on a website. Gunter Demnig’s Stones of Remembrance (Stolpersteine, literally: stumbling stones) are also very appealing to me. Since 1992, the German artist has been installing small concrete paving stones with brass plaques in front of the former homes of Nazi victims, engraving the names, dates of birth and death and briefly mentioning the fate of the former residents. There are already more than 90,000 Stones of Remembrance in European cities – only about in Poland, including five in Zamość (at 10 Zamenhofa Street, they commemorate the Wolfenfeld family).

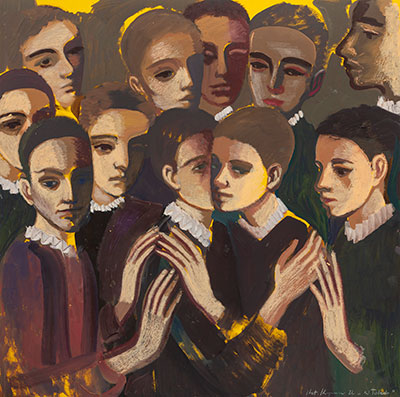

Sadness, grief and a longing for people who are no longer with us link all of Katarzyna Karpowicz’s paintings on display at the exhibition at BWA Gallery in Zamość. Although we can find many leitmotifs that have appeared in the artist’s work for a long time (water, tree branches, soap bubbles, blue marbles, masks, urban spaces with arcades, black suns and children in caps), this time they resound quite differently and take on additional meanings. After all, the painter shows the Shebreshin world just moments before the apocalypse, a shtetl frozen for a moment just before the Holocaust, whose dark-haired inhabitants who ‘look bad’ already seem to anticipate what is about to happen. In turn, looking at these canvases, we have a tragic certainty of how it will all end.

Two women, friends holding hands, will be separated in a moment on the ramp leading to the camp. A wedding is really a funeral. The Klezmer orchestra is about to break up – there is probably a reason why Night Orchestra is a diptych, a work in which separation and parting are written into in advance. The street where crowded passers-by are probably eating the last ice cream in their lives, is about to become deserted. I can’t help but associate the naked figures in the river with the foreshadowing of a shower that will bring death. Being aware of the history and context changes my outlook and takes away the innocence.

A minyan, a quorum of ten men, is required to recite the kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead (although Reform Judaism allows women to participate). Looking at the paintings in the Non-Existence series, painted by a non-Jewish woman standing alone in front of her easel, one nevertheless hears involuntarily the words of a prayer beginning Yitgadal v’yitkadash sh’mei raba...

Katarzyna Karpowicz’s Shebreshin paintings evoke another association in me: that of the Pinkas haKehilot project – an encyclopaedia of Jewish communities from their foundation till after the Holocaust, published by Yad Vashem in Jerusalem since the 1940s, written either in Hebrew (Pinkas haKehilot) or in Yiddish (Yizkor buch). In addition to historical information, descriptions of places and buildings and personal accounts, they also document the fate of those who did not survive. A memorial book dedicated to Shebreshin entitled Sefer zikaron li-ḳehilat Shebreshin was published in 1984 in Haifa. It includes reproductions of dozens of archive photographs, including one showing a large Jewish family in the interwar period. When I look at them, the image that immediately comes to mind is the paining Box of Dreams – monochrome, mimicking black and white photography and clearly different from the rest of the work. Alas, these dreams will not come true.

The artist is, after all, writing a similar painterly book of remembrance with the strokes of her brush. In a gesture of embracing, she symbolically brings the dead and strangers – but still loved – out of the Sheol of oblivion, gives them faces and turns non-existence into existence. For that tender gesture of an embrace, for your yizkor buch, thank you very much, Kasia.

Photo:: Moshe Milsztajn with his family, interwar period. after: Sefer zikaron li-ḳehilat Shebreshin, Haifa 1984, p. 509.