Tales of the Shtetl

My uncle Meyer, a man of artistic talent and a known lover of several women, was ready to be wed. His was to be an arranged marriage to an 18-year-old beauty, Zipporah, from the city of Chełm. He had met her a few times, and then told stories of how wonderful and independent she was.

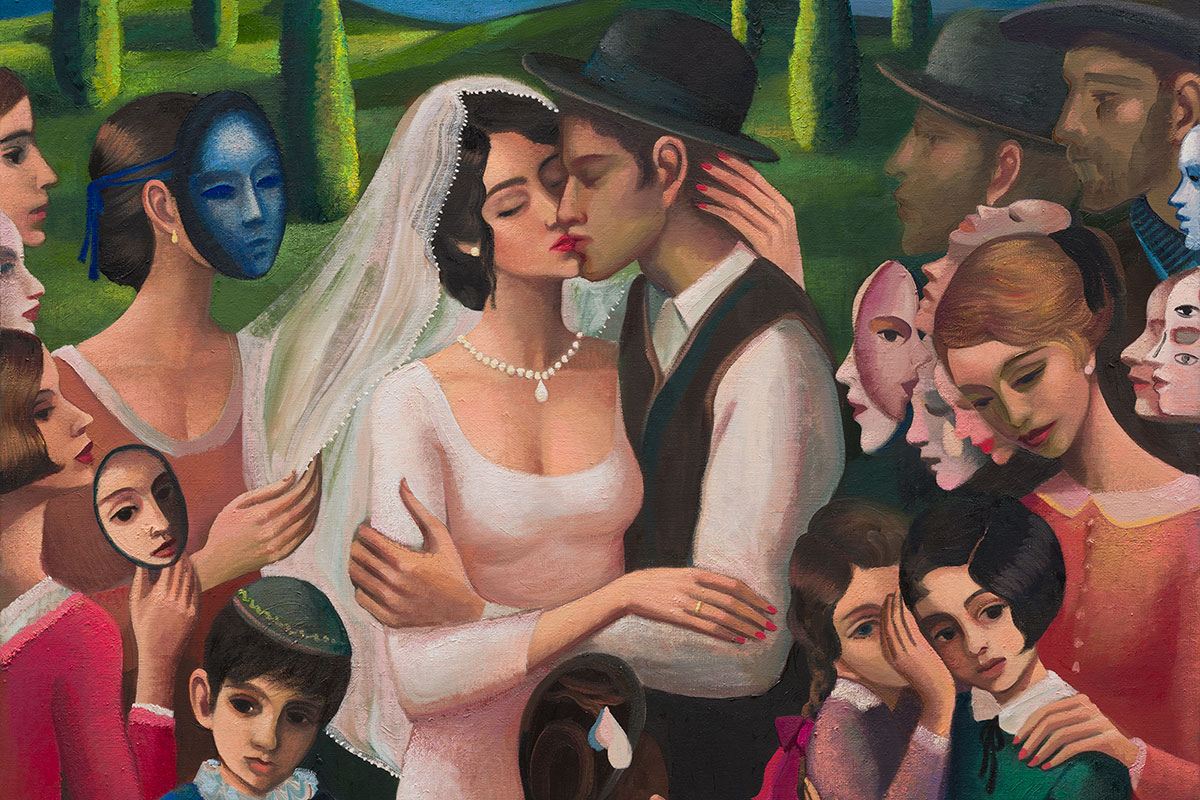

The whole family set out for this grand celebration. Everyone put on their best clothes. We knew there would be a wonderful ceremony, after which we would bring the bride home. My uncle had even built a new home for her.

Preparations for the wedding went according to plan. All the men accompanied the groom as the ketubah was set down. The women took care of the bride, preparing her to put on the veil and enter under the canopy. Suddenly, we heard a chilling scream coming from the part of the house where the women had gathered. We all rushed there and a horrible sight appeared before our eyes. Several women with large shears in their hands, surrounding the bride, were shouting. She, on the other hand, was standing on a chair holding a large kitchen knife to her heart.

‘If you come one more step closer, I will plunge this knife into my heart! I will not let you cut my hair!’, she exclaimed.

Cutting the bride’s hair on the wedding day was an inviolable custom, dating back to the days of wars, robberies and rape. The inhabitants of the shtetls thus tried to make young women as unattractive as possible to invaders. For Jews in Eastern Europe, this had become part of tradition, an obligation, almost a divine commandment.

I remember that every married woman, even my beautiful mother, wore a heavy, nasty wig called a sheitel or a parik. They never allowed their hair to grow back and covered their heads with scarves and shawls.

My future aunt was the first woman I knew who decided to defy the age-old injunction. There was shouting, pleading, tears being shed – all of which took quite a while to finally end in a compromise. Reason prevailed. One woman was allowed to trim the bride’s hair a little, but no more than ten centimetres. Zipporah had won. She came home with us, never wore any type of wig, and always openly displayed her beautiful long hair.

I adored the couple and when I started writing youthful poems, it was to my aunt that I showed my first attempts at poetry.

In 1942, the Nazis invaded my town. The entire family, including the long-haired aunt, was murdered. According to the witness, she remained brave to the end. She was holding her newborn daughter in her arms when the Germans shot them during a mass execution. It was not God who punished her – He was busy with something else when people turned into what some are still today: merciless beasts.

Fragment of Philip Bibel's memoir Tales of the Shtetl, Polish version edited and translated by Tomasz Pańczyk.