Non-existence

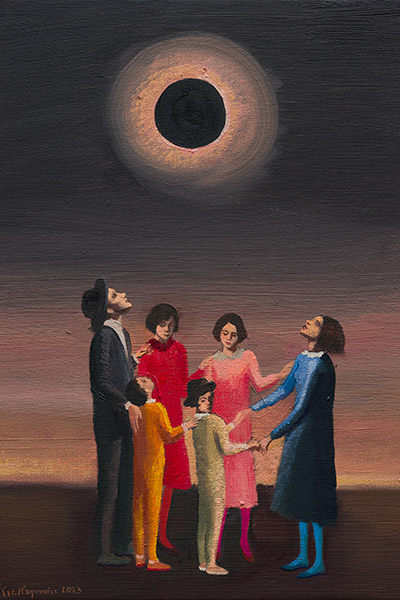

Drawing from the bag of colour glass marbles, the boy usually chose the black one, turning it in his hand like a prophecy. A bad omen, the adults would say, if they knew. The colour black does not fit with childhood.

There will be darkness in the hiding place, the enveloping yet ominous darkness of double-walled storage rooms, cellars, and attics. The glass marble clenched in the child’s hand will lose its ominous colour, but the boy will not escape his sinister destiny.

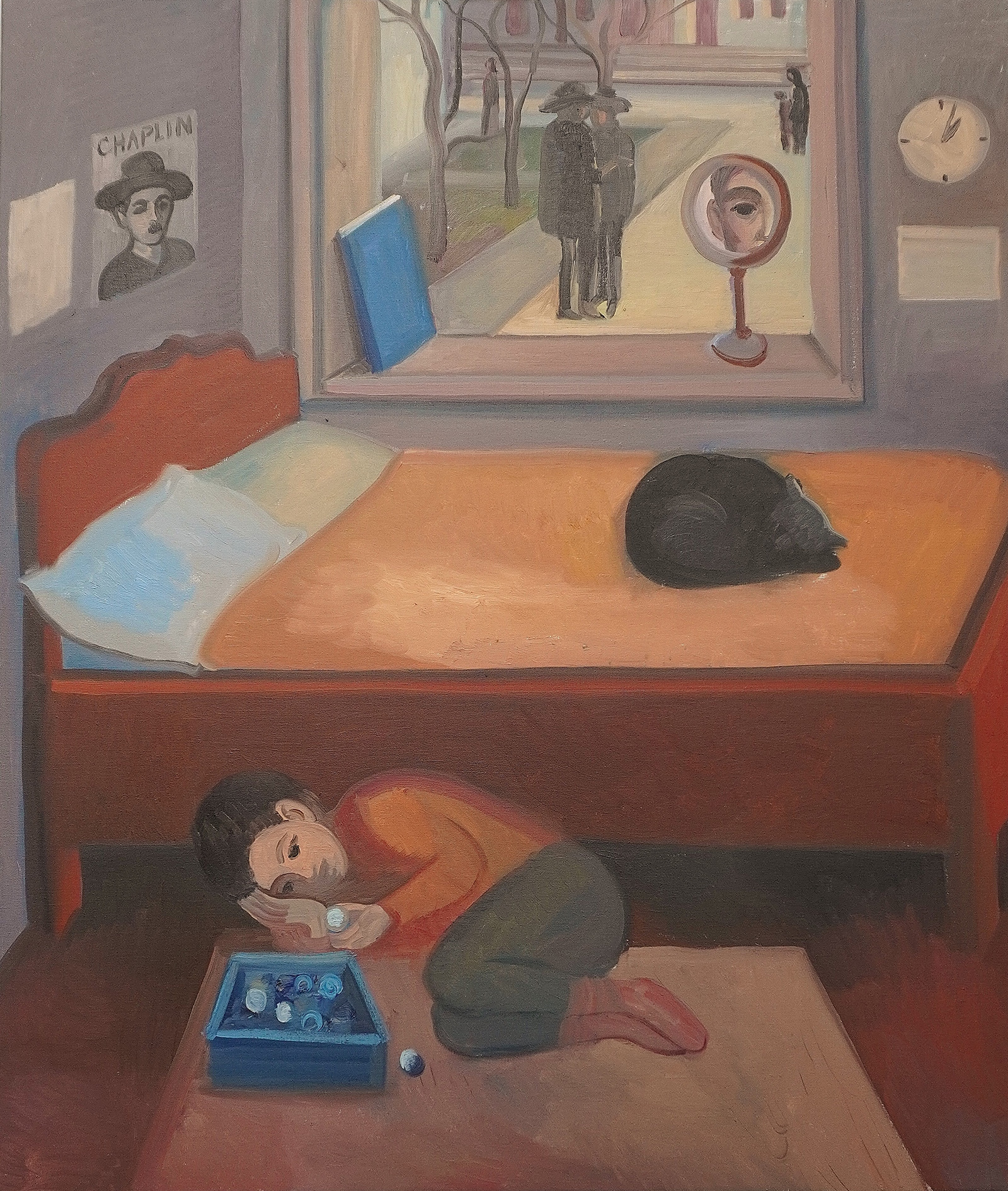

It should be like this picture: a room in the family home, a poster of Charlie Chaplin on the wall (oh, how Mum and Dad laughed at his films; the cinema in Szczebrzeszyn shook with bursts of laughter time and again). You can hide under the bed – because who hasn’t – from your mum when she calls you for dinner, from your dad whose caring face is reflected in the mirror. This is a story from before the Holocaust; it is a memory, an afterimage, a pious wish. And it wasn’t the black marble that changed reality. The painting is not finished, because how do you paint the darkest destiny?

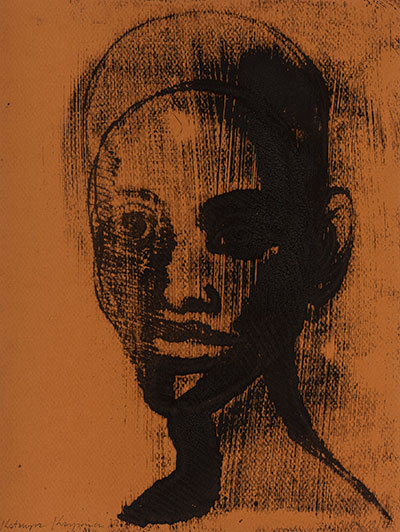

The Jewish boy from Szczebrzeszyn has appeared in Katarzyna Karpowicz’s paintings for years. He wanders through the town, stops in front of the patisserie, dreams of balloons from the street vendor, looks into the eyes of passers-by, and moves on. In psychoanalysis, travel and wandering symbolise death.

A year ago, a neighbour from Szczebrzeszyn told Kasia about the son of a local dentist who lived in the house next door. Sent by his father in the care of a woman ‘who looked to be good’ to a friendly Polish family in Biłgoraj, he was caught and imprisoned. He did not survive the war. Nobody knows or remembers his name.

The painter gave him the name Akiwa. Only recently did she learn that Akiwa means shelter.