Precision of Contemplation

Andrzej Sadowski’s study time at the State Art School in Łódź (today Strzemiński Academy of Art Łódź) ensued under the sign of geometric abstraction. By then, professors painting with the help of a ruler were considered to be “artistic gods”, as malicious comments put it. But what can an artist do with geometric abstraction if he possesses a realist’s soul and lives in a period still overshadowed by socialist realism? Instead of constructing his world according to geometric rules, he needs to look for other models. He is a great illustrator and he can use any stylistics. But he needs to find his own way.

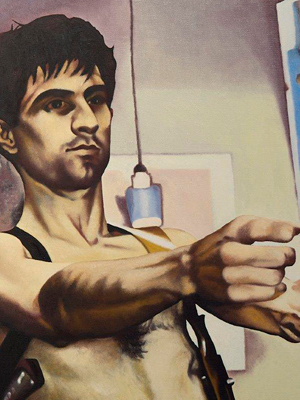

At an exhibition in 1974, four years after his graduation, Sadowski presents his pictures. One can notice that the artist is attracted by expressionism and metaphoric painting. He looks for dramatic, catastrophic motives like war, and confronts them with a mythical, post-apocalyptical arcadia. He creates contrasting colour compositions. But he also creates realistic still lives and portraits. This is here where his flirt with surrealism begins. That means metaphoric expressionism or magic realism. Then the scale turns towards realism. New models appear, among them the disturbing realism of Jerzy Krawczyk. Gradually, deformation of people disappears from Sadowski’s pictures. He paints smoothly now, mostly with acryl. He applies photography, creates objective and seemingly cool reports from everyday life. He paints politicians (Salvador Allende), sportsmen (Włodzimierz Lubański) or socialist superproductive workers, “stakhanovites” as Russians used to call them. Human remains his focus, including specific events he or she is involved in, face confined within a cage of time, taken out of a newspaper or TV news. He does a kind of a painted documentary.

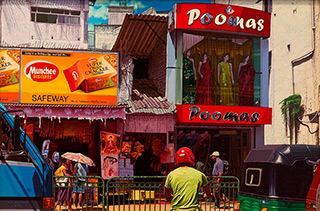

The beginning of the 1970s is when photorealism appears. The first real contact with it follows – in Louis K. Maisel’s Gallery in New York City. It is a revelation. First reproductions of the masters’ paintings in colour magazines; Chuck Close incessantly experimenting with form and his portraits imitating photographs, Davis Cone and Robert Cottingham obsessively photographing traffic with their brush, pulsation of theatre ads and neons, in sun, in rain, in fog, recording the elegance of brand logos and advertisement fonts. Finally Sadowski’s favourite, Richard Estes and his panoramic portraits of American cities, Rome, Paris, Florence, almost total, bursting the frame. Sadowski dedicates one of his paintings to him: Düsseldorf – escalator, hommage á Richard Estes (1978). Photorealism seen from the perspective of a communist country must have delighted with its austere, sterile poetry, precision, breadth and the very subject – the portrayed reality of a modern, Western civilisation. Sadowski follows this path. He resigns from a visible texture in his paintings. His art accepts the role of a transparent medium transmitting the image of reality. But even in these seemingly objective works one can still see the author’s selection of motives and his personal point of observation. According to Grzegorz Sztabiński, Sadowski’s paintings “persuade us to question the idea of objectivity of photographic image”1. The artist decisively abandons his previous way. He begins his great romantic grand tour, the tour that has been lasting ever since. He focuses on sceneries. Veduta becomes the most important subject. Already at the beginning of this tour it becomes clear that he is interested in the beauty of architecture and the history hidden behind it. Communism destroyed Poland, homogenised and pauperised its society, confining it within a peculiar parody of Le Corbusier’s ideas –precast concrete cages. Outside the big cities, the countryside was frozen in vegetation.

But there was still the old Łódź, beautiful centre of Cracow, historic Wrocław, fragments of Zamość or Lublin. They all become themes of Sadowski’s paintings.

Then his first trips to Prague, Göttingen, Kassel, Berlin, Brussels. From the bleak perspective of Poland of that time they work like a powerful hit; of architectural beauty, cleanliness of urban space, luxurious car and motorcycle paint and chrome shine, and – after all – of the level of everyday living culture; museums, churches, cosy cafés and wine bars, rock music, openness and kindness of people, the lifestyle completely unknown in the socialist Poland. This is not about the different level of wealth. It is just an escape from the communist shed into a space of freedom. One could say, though, that there was also a normal life going on in the Polish cities under communism. As Czesław Miłosz wrote: “In the end people move, work, go to theatres and organise trips. But there is something elusive in the atmosphere of socialist capital cities like Warsaw or Prague. The common fluid, emerging from exchange and summing up of particular fluids, is bad. It has an aura of power and misfortune, internal paralysis and external mobility”2. It is just this socialist, Polish reality that Sadowski escapes in his art – into the unreality of the Western world.

What do the American or Western European photorealism of the 1960s and Poland’s photorealism of the 1970s have in common? Is there anything like Polish photorealism or is it just a method of painting that imitates its American model? In the art of the West, photographic realism arose from the disapproval for consumption and civilisation of items, from the boredom of the welfare and the emptiness of industrial uniformity. However, in the European countries under the Soviet domination it was rather seen as an affirmation of the beauty of luxurious objects, set in a highly-organised urban landscape. First of all, however, one has to realise that in the Polish art, entangled into the nation’s dramatic history, there had been long-lasting artistic positions, among them romanticism and symbolism, especially. They are remnants of the 19th century, the time when art worked as a refuge for Poland’s endangered national identity. At the break of the 19th and 20th centuries, when romanticism and neoromanticism experienced their climax, artists managed to grasp the essence of the Polish landscape and the “pure” Polish mind. This approach was somehow still palpable in the Polish photorealism of the 1970s. Zbysław Maciejewski and Łukasz Korolkiewicz created their paintings with its poetics. Their point of beginning is still photography. The first one puts a colourful, linear raster onto his southern Arcadia dreams of blue shadows sifted through arbour lattices and flower garlands, or of cypresses lasting in the southern heat. The other traces nostalgic black and white dominated by silver greyness, urban alleys, backyard crosses and shrines of the snowy time of the martial law, moulded walls, still pond surfaces with duckweed and little girls playing nearby. It is a very different reality from the one shown by the Western photorealist paintings, rather a sentimental travel into the past of Proust and Whistler. Yet another time in the Polish art we can see the discrepancy between stylistics, taken from the Western art, and creative stance, arising from the local tradition. It was also the case with the assimilated impressionism and japonism of the 19th and 20th centuries, which ended as something very different from their respective originals.

What about Andrzej Sadowski? Why does he paint streets, cars, motorcycles? He considers himself to be a documentarian. But he says it only out of spite. A layman could think that art has no other ontological status than nature, that a painting is not different from a perfect colour photograph, that photography is just identical with nature. However, from thousands of captures the artist chooses only a few that interest, delight or move him, fragments of scenery that he can enter dialogue with. Afterwards, in course of painting, direct observation is replaced with the artist’s memory, working by its own rules. The truth of nature must now give way to creation and the emerging, immanent structure of painting. At the edges of the composition there are fragments of cars or motorcycles, evading the frame like passers-by or carriages in Bonnard’s paintings. Elsewhere, there is a pointillistically painted fragment of a sun-bathed, lime wall in the foreground, sterile in the heat. Similar effects can be found in Zbysław Maciejewski’s works. At this stage, nature is not a point of reference anymore – art is. Art enters into a dialogue with art. Big grand tour. Narrow alleys of Aachen, Heraklion, Venice, towns of Brittany, Crete. These vedutas stay closer to the century-old graphic landscapes of Jan Rubczak and Józef Pankiewicz than to the paintings of American photorealists. The admiration for an architectural motive goes from one artistic generation to another. The same “alley motive allows us best to follow the stylistic evolution of graphic output of both Pankiewicz and Rubczak, possessing many common features with Whistler’s transformation into ouevre, who in etchings like Wych Street , Quiet Canal and Clock-Tower modified the composition of an urban alley, so typical for Paris sceneries of Meryon” – writes Irena Kossowska.3 And so, one could go back as far as to the 18th century vedutas of Italian masters. This is because art feeds art and remains in an incessant dialogue with the art of past centuries which is often more intensive than the one with the contemporaneity.

Why does the perfectly drawing Sadowski need photorealism at all? Why photography? One could pose a similar question to Wojciech Weiss, a brilliant artist from a century earlier, a question about the auxiliary photographs to his most splendid, dishevelled, neo-romanticist painting improvisation – “Poppies” from 1902 – that have been preserved in the family collection. Well, photography is not used for documentation of any specific fragment of nature here, but for recording of a currently experienced moment in which the painter encounters, in dismay, a phenomenon that is new for him. Photography works as an auxiliary memory, a matrix bearing a particular expression open to metaphysics. It is distilled from sensuality, material existence and only a thin wall divides it from a silent persistence – from esse.

A creative method developed to the extreme changes its sense. Young Claude Monet creates a spontaneous feeling, notes down a pure impression – a red, sunny sphere, hanging in the morning above the blue, misty haven of Le Havre. Old Monet creates in the series of Rouen cathedral façades or Water-lilies a virtual abstraction – expressive, speaking with a conventional, suggestive colour and rich texture. The 19th century realism recounts the world with similarity of appearance. Photorealism develops this model to the edge of mimesis and, with the help of applied techniques, crosses it. Ultimately real becomes unreal, open to multiple interpretations, symbolic.

Heat. Empty streets. Tangible presence of the sea, even if still cold and unaccessible. Seagull squawk. Adverts that no one reads. Pink wall in a sun’s glare. Unique moment, real and unreal at the same time, disappearing in a few moments. Bricked walls covered with a low sunlight. Long, explicit shadows. Suddenly, we find ourselves close to the painting of Hopper or Chirico. No surrealist manifestos are necessary, scarily logical and rational, by the way.

The essence of the great, romantic voyage is the joy of free choice of way – one of many – and of free choice of scenery – one of thousands. Great joy of creation. Grasping the play of lights and shadows at a gothic church façade or an old wall, the roughness of a cobbled street. Seeing how sunshine animates the noble beauty of old buildings. Following flickering shadows and sunny reflexes on old façades, churches, stone cornices, panels, wall textures, covered in a damp twilight and throwing a dark shadow onto a pavement. Coming into a violet shadow zone, entering into an area of sunshine, dominated by lemon yellows, into the obviousness of shapes, bareness and dryness of colours. Questioning veduta’s realness, multiplying it through reflexes on shop windows, shiny car bodies, canal waters, crinkled by wind.

In Sadowski’s paintings, shiny car and motorcycle bodies are like – as Stendal used to say about novels – “mirrors strolling along a road” (in this case, perhaps rather rushing through roads or parked along them). They reflex the time that has passed. Elegant cars and motorcycles, shining with their paints and chromes. Where does the artist’s fascination with a luxury object come from? Let’s go back to the end of the 19th century for a while. In the paintings of James Whistler, Japanese trinkets, fans, screens, china cups shine in twilight. A similar, blue cup is put on a table in Portrait of Paweł Nauen by Olga Boznańska, as if especially created for the delicate, manicured hand of this Munich dandy. Exotics of an oriental item. Legend of a long voyage. Object as a vehicle of dream, a pretext to go beyond “here” and “now” of a living room or a painting studio. Over one hundred years later, space and time can be deceived in a different way. It is enough if one sits on a Harley and feels its power between one’s thighs or starts a Lamborghini with a squeal of tyres. Sadowski is a mature artist already. But it is easy to imagine him as a small boy, unable to take his eyes off a Harley-Davidson in a shop window. Maciej Mazurek wittily notices that in Sadowski’s paintings “cars and motorcycles become objects of desire” which the artist has “promoted to the importance of acts”.4 It is neither a beautiful, refined trinket nor a naked woman anymore, it is a machine. This is the 20th century. Fernand Leger wrote: “Every object-machine possesses two material characteristics: one is usually a painted, light-absorbing surface with a constant value (architectural value), another is a light-reflexing surface (mostly white metal) that plays the role of unlimited fantasy (painting value). Light is what determines the extent of diversity in an object-machine”5. Is this not what takes place in Sadowski’s paintings? Aren’t cars’ and motorcycles’ surfaces painted by him dissolved in the colour structure of the painting, don’t they counterweight architectural surfaces – bright and sunbathed or immersed in shadows? Doesn’t the white metal of wheel rims, lists, mirrors become a tool of artist’s fantasy, doesn’t it glitter, doesn’t it work as a function of joy? In those works the indulgence of grand tour and delight over the southern nature unites with the joy of coexistence with a beautiful object. The tension within these images results from the confrontation of the power of modernity, hidden within the form of a machine, of its potential dynamics, with the static melancholy of the architectural background, past time, clotted in architectural forms.

Dark, blue, compact shape of a Mini Cooper on the background of a pink plaster, falling off a sunny wall in Carpentras. Backstreet like thousands of others. But this one is seen at a morning hour, when the sky blue is still wet, when everything still remains a pure hope. Church bell ringing nearby. Truffle market to begin soon. In order to see all this, one needs to depart for a trip first, to leave one’s everyday life behind, forget everything, sit on a kerb in order to contemplate a stone wall. Because Sadowski, just like the old Japanese masters, unites precise description of nature with its contemplation. This is exactly what makes the essence of his art.