Colours of the Senses

Wika Kwiatkowska in conversation with Katarzyna Karpowicz

Are you pulled towards the South?

The sunshine and painting of the South – strong in colour, in light and shadow, very contrasting – has always fascinated me. But I look in all directions. Lately, I’ve been pulled to the North; I think these regions could bring yet another colour into what I do.

And what do you see when you think ‘Spain’?

First of all, View of Toledo by El Greco, a painter who has always amazed me with his expression, his totally new and individual way of thinking about painting. His paintings have a dynamism and movement, and that’s something that practically hypnotises me about Spain. For years, I’ve been looking at them not like a tourist, but like a local, because I visit my husband’s family there – Juan is from Segovia. This Caravaggio-like gesticulation, expressive faces I know from Medieval Spanish painting, this energy and vitality, they’re fascinating. The Spanish do not hide their emotions, they let themselves laugh loudly, show unrestrained displays of affection, even between strangers in the street. Men are more effusive, cousins tell each other ‘I love you’. I was also embraced there, kissed from all directions.

Was it a culture shock?

Very much so. I didn’t know that as someone from Poland – that is, from the North – I was so cold (laughs).

You say about yourself: untouchable. Is reducing physical distance difficult for you?

Yes, although it doesn’t shock me and doesn’t cause as much discomfort as before. Becoming friends with these people, I’m slowly opening up to touch, to kisses. But I also maintain my own sensitivity. Sometimes I make the distance clear and hold out my hand instead of kissing a stranger, as is the habit in Spain (laughs).

You called your latest exhibition Cuentacuentos. This Spanish word can be translated as ‘storyteller’. Do you feel like that’s what you are?

Yes, because I treat painting a little like a second language and a space in which I tell myself stories. I’ve always created from the imagination, drawn from the memory, made up my own stories and characters. They later wander through my canvasses, and I ‘talk’ about whatever is bothering me. These are universal stories of love, transience, youth, maturity. I’ve wanted for years to put on an exhibition called Cuentacuentos – sort of a fairy tale for grown-ups. I love the way this word sounds.

What are you telling stories about now?

About tenderness, physicality, the celebration of the trivial things that are seemingly banal but actually important – those embraces, the caring, togetherness at the table, sharing dessert together. It’s being juntos, together, like going out with the whole family for churros with chocolate. Actually, what I recommend to everyone is a trip to the local churreria, where they serve these long pastries, which you dip in chocolate and drink freshly squeezed orange juice.

You painted both the sweet Churros con Chocolate and Ponche Segoviano with a mysterious cake on a table for two.

It’s my favourite dessert (laughs). None of the locals like it the way I do because it’s probably a little like if I, a Cracovian, loved obwarzanki pretzels. It’s a local dessert from Segovia: a moist sponge cake with vanilla creme and marzipan. Moist, sensual, soft, simply marvellous.

The energy and colours of the South have strongly influenced the climate of these works, haven’t they?

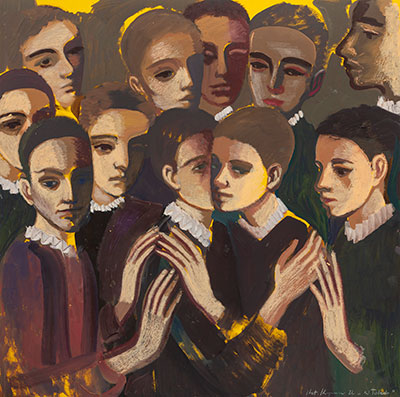

Yes! I wanted to bring something exceptionally beautiful and good from Spain, something that I sometimes miss in Poland – colour, intensity and the vibration of this energy. I wanted each of these paintings to be strongly defined and saturated. Thus, a lot of yellows, pinks, various shades of red – from dark to bright, bloody. There are also oranges, greens and blues. All these paintings come together in the colours of the rainbow.

Was this something you intended?

No, not at all. But when I was in Spain the last time and had the exhibition almost completed, I took a walk in Madrid and noticed that there were these colourful, beautiful rainbow flags in windows everywhere. It was October, Pride month, and I thought, ‘Perfect! It’s a sign that my rainbow-coloured exhibition is an expression of all kinds of tolerance and love’.

In the painting Happy Life, two young men sleep under the open sky, twined together in a loving embrace. Tender Hand shows a gesture between two women.

That’s true. I have many friends who are part of the LGBTQ+ community and I introduce these relationships and motifs in a natural way, so I don’t even notice it. I paint intuitively and perhaps I’ve transferred to the canvasses what I noticed in Spain: people there enjoy life and love, without judgement. That kind of approach is close to my heart.

You examine femininity and masculinity quite closely here. Do you like the sharply drawn, sometimes provocative, sometimes emotional women from Almodóvar’s films?

That’s interesting because I draw inspiration from films quite a lot, actually. I think I’ve seen all of Almodóvar’s films, and even though he’s never been my favourite director, apparently he’s stuck in my mind. I remember when I saw women in Spain, with their bold gazes and red lips. I thought, I had them on my canvasses already, but now I would draw them even more clearly.

Seductive, showing the world their full femininity?

Exactly: they’re not embarrassed, they accept themselves. And they don’t feel guilty. It’s interesting to me that Spanish women allow themselves to be so seductive and sensual. Like in flamenco.

Are the fans in their hands also like in flamenco?

In flamenco the gesture of the woman’s hand and the free use of the castanets or a fan is incredible on its own, and it makes for an attractive motif in a painting. The gesture of concealing and revealing builds tension and adds mystery. And for me, a painting in progress is also always a mystery.

When I was looking at Heart of the Mother, I was reminded of Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth. Was that an inspiration for you?

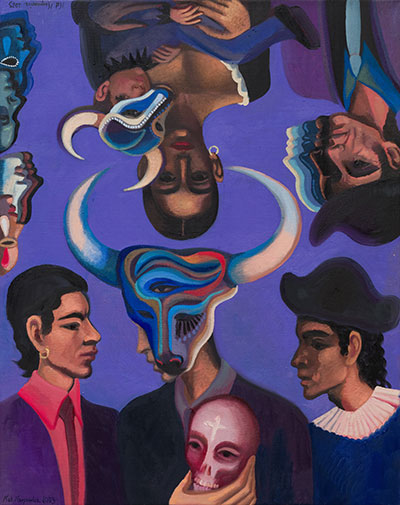

I love that film! And this very organic mask with the eye could indeed remind the viewer of it and be terrifying. The painting is one of the revolving ones I painted for this exhibition. It contains two different but equally important stories. On the one side, we have a skull held by a man concealed with a bull mask. On the other side is a woman holding a small boy, who is also wearing a bull mask. I wanted these two stories to take place in parallel. So the viewer could turn the painting and experience it again each time.

Is it a story of masculinity?

Women raise men. First they’re little boys, sweet and sensitive. Then they grow up, into toreadors, for example. It’s hard for me to understand and accept. I paint these toreadors as people who are victims of the system, a certain culture and imposed social roles. Men are told that they have to be strong, plant a tree, build a house and raise a son. A woman has to be forgiving, tender and caring, even if it’s not her choice. If a person doesn’t break these patterns, doesn’t realise that something’s not right, they could live their whole life wearing someone else’s clothes. A little bit like in the theatre, putting on a mask and playing a role that destroys them. But this exhibition also features a painting with the figure of a father holding a white dove. His sons stand beside him, and the father is wholly gentle. It’s a nod to the masculinity I also see in Spain, where these very manly men suddenly become tender, loving and caring.

On the one hand, we have sensuality and vitality, on the other – melancholy.

I dedicated my previous exhibition, Non-existence, to the Jewish community from my home town, Szczebrzeszyn. It was very important to me, but also difficult. That’s why I decided the next exhibition had to be about existence. Cuentacuentos became a turning point for me, back to life, a celebration of the everyday. I painted pictures that I wanted to show flavours, colours, friendship, love, interhuman exchange, sensuality and in general, joy of life. I told myself, ‘I want to turn towards the light now, away from the shadow, darkness and death’. And suddenly I noticed that everything happens in parallel. That you can’t just cut out a piece of the darkness from the world.

Are you looking for a balance between light and dark?

I think that with this exhibition, I’ve found it. I really envied the Spanish their dolce vita. But then I saw that they also have their problems. They struggle with themselves, there is tolerance, but also intolerance. There is fatherly love and dedication to their children, but also machismo and violence. The mask fell and I understood that life everywhere, all around the world, is made up of light and dark.

You paint your pictures all together. Does it ever bother you that none of them are finished for several months?

On the contrary. It would bother me if I only had one painting on an easel and had to paint it from start to finish. Instead, I have, let’s say, ten paintings on the go, and I don’t paint them all each day. I come into the workshop, and I decide, ‘Today I have the energy for you’. So I take the painting and I talk to it, working on it for half the day. Then I take the next canvas, which can be just a sketch, for example, and I work on refining it for the rest of the day. And so on, every day, for months. For this exhibition, I worked on sixteen paintings. But at the very end, I decided I wanted some small format works. So I painted another ten.

Are there works you don’t want to give up?

I haven’t mastered assertiveness enough yet to set aside a painting for myself from each exhibition. So far, I’ve managed to keep two. But I would like to pick a painting from each series and at the age of seventy, have them ready for an exhibition.

The next one will be about the North?

I have an idea for a series that happens on another plant. I dream of setting out with a sketchbook, looking for inspirations. Lately, I’ve been thinking about the North, especially Iceland. But I haven’t bought the tickets yet.

Would your Spanish husband want to go with you to cold Iceland?

I think so. I’ve actually become more Spanish, and he more Polish. He has blue eyes and light hair; I have dark eyes. Juan shushes me to speak more quietly when I get excited about something as we walk down the street. And he glances through the curtains at what the neighbours are doing (laughs).

Have you thought about settling in Spain?

No. I’ve experienced living outside of Poland, and I know that it would kill me to miss my loved ones and my well-trodden paths. I like the sun, but also the Krakow melancholy.

In Malaga, at the Museo Picasso, you pointed out the quote, ‘It takes a long time to become young’. Is that your current motto?

I understand Picasso’s words to mean that in order to become young again, you have to reject the routine of perceiving the world and yourself. We often live in an illusory self-conception that limits us and makes time, which flowed slowly in childhood, start to slip away. That’s deadly to people and to creativity. When we’re children, we can see magic in the details, in daily life, and then we lose it somewhere. Picasso was open like a child to what could happen. Of course he was also quite a rascal (laughs). For today, I think we shouldn’t treat ourselves and everything else so seriously. It’s good to look at your life upside down, turn it around for a moment and see what it looks like from the other side.

Like in Alice Through the Looking Glass?

I love Alice Through the Looking Glass and Alice in Wonderland! I read them a lot as a child, and then later, as a teenager, I went back to the books because of the illustrations. And I think that Alice, and the childlike sensitivity, resound in my paintings.

Shortly after graduating from the Academy of Fine Arts, you heard something that’s stuck in your memory: ‘Kasia, you can’t be so nice. Remember, nice girls go to heaven, naughty girls go wherever they want’. Are you naughtier these days?

I think I managed to break through my correctness over time. But I think that my niceness has its benefits, and that’s why I stick to it. I use it to build a certain distance between myself and my surroundings. It’s safe, and it lets me keep space for myself. On the other hand, the attitude that could free me from this niceness brings certain challenges you have to be ready for (laughs).

The women in Almodóvar’s films are naughty.

I’m learning this naughtiness. That’s my resolution for this year!