An idea hidden in things

Buildings, edifices, objects. Anchored in our memory, in our thinking about cities, outskirts, in images of different journeys, in perception of a rural road, a sea shore, a terrace, a backyard. The roughness of concrete, the smell of timber, the vermillion of brick, the colour of neon. A house, a palace, a factory, a station. An arbour in the park, a gateway, a swimming pool, a springboard, a gasoline station. Light falling onto the floor, walls, the asphalt of the road. Encoded views, landscapes complemented with architecture.

For me the presence of some edifices hides a mystery,

writes architect Peter Zumthor in his book entitled Thinking Architecture. They simply seem to be there and one never pays too much attention to them. And yet you cannot imagine the spot where they are without them. These buildings look strongly anchored in the ground. They make that impression of being a natural element of the surroundings and say:

I am how you see me and I belong here.

And then he adds: I have got a passionate desire to design buildings that, in the course of time, and in an obvious way, merge with the form and the history of their location.’

A dream that sometimes comes true.

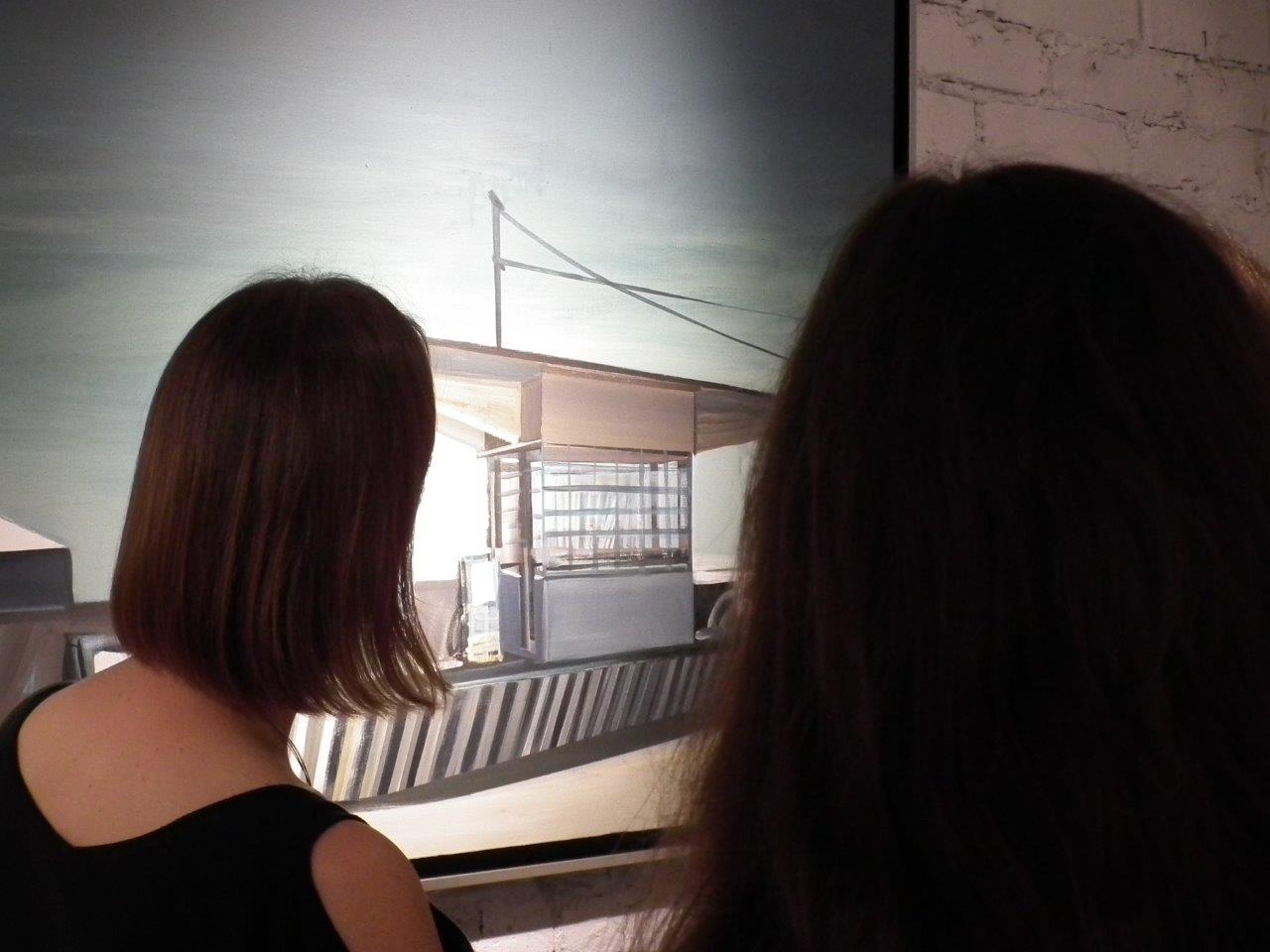

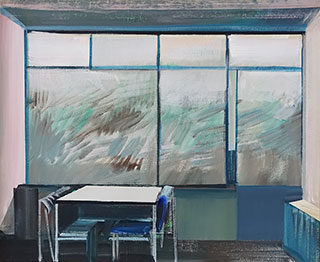

In Warsaw it’s the Palace of Culture and Science, in Katowice – Spodek. Postcard frames, TV montages, photos that have been googled out. The very first image of Copenhagen may be the statue of the Little Mermaid, but it might also be the view of the Royal Opera House emerging from the water. In thinking about and painting architecture Maria Kiesner sees a motif that is worth painting. She sees it in famous objects and well-known symbols of places, as well as in these smaller, forgotten ones that may be found somewhere on the margins.

She absolutely loves villas by modernistic classics, the clarity of project and design, the simplicity of form and post-war buildings of socialist realism. There is some kind of silence in this architecture,

says she. Some nobleness of proportions, apt distribution of accents.

But she also notices industrial buildings that merge with the landscape and human consciousness, e.g. the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, the Silesian factory chimneys from the beginning of the 20th century, or contemporary wind turbines.

Sometimes these are accents emphasizing the beauty of the surroundings – when an appropriate architectural form makes the landscape complete, and some other times these are really just disfiguring and dominating landmarks. She paints them in broad panoramas, showing their monumentality, their beauty and sometimes terror, but she also chooses a more intimate perspective, focusing on details of architecture, on a single element.

People have always lived in a landscape and that’s where they have worked,

writes Zumthor. Sometimes landscape suffers from the fact that we live and do our jobs in it. Nevertheless, our history of dealing with land is – for good and for bad – written in landscape and, probably therefore, we call it the cultural landscape. Thus, apart from the sense of belonging to nature, there is also a landscape-based feeling of relation with history.

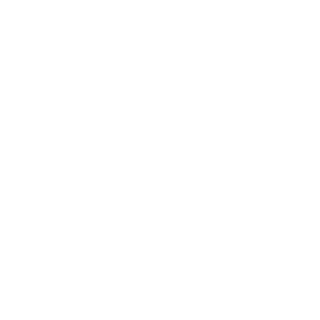

Objects in the paintings by Maria Kiesner are autonomous beings present in the painting’s space. Even if we recognize the place, recollect the surname of the architect, it’s either a matter of secondary importance or completely unimportant. Kiesner does not paint from nature – she selects old postcards, photos in albums, reproductions, film frames from YouTube.

In her paintings objects get nobler – freed from decorations, details which are, in the painter’s opinion, unnecessary. They gain some kind of universal character and lose connection with a specific place previously attributed to them. ‘As a result, buildings look a bit like paper mockups,’ states the artists. They do not have their weight and are idealized. And I do like them that way.

Alienated from reality, they become anonymous, they enclose mysterious emptiness and, at the same time, allow their space to be experienced. The atmosphere of these paintings and their metaphysicality is immensely important and characteristic.

There is no idea

, says Peter Zumthor, except for the one hidden in things

.