City-diaries

If the history of architecture can be compared to a “collection of fiction”, because every new interpretation idealizes our knowledge regarding the past, then Jolanta Wagner’s works “The History of Cities” always viewed from afar, from a distance that lifts us literally, mocks the very laws of optics, in an inverted order. From flat rugged sands emerge city-dwellers, gaudy, chattering, always keeping their personal belongings at arm’s length, building their brick walls in disciplined rows, pursuing rank and file conformity, a city labyrinth, whose streets and alleyways suddenly end or else lead nowhere.

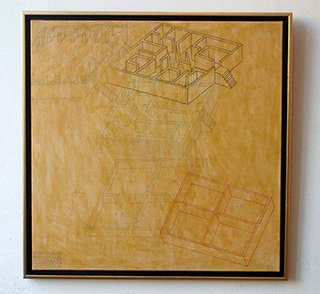

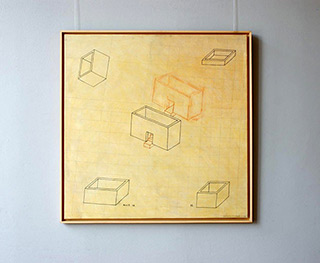

The works of Jola Wagner are an uninterrupted voyage, structured as a story within a story, written in time and space, as a live reportage from the here and there. Although on “Portfolio” her works are systematically arranged into a vanishing order: fading colour, bleaching, revealing half tones and increasingly raw under painting. Lately they are pre-aged, readily drawn over graph tracing paper, archaic remnants of a non-computer era. Yet, the portfolio of this artist lacks something of a great importance – a chronological order, details regarding the techniques and materials used and the works’ actual dimensions; the titles are not actually titles but instead they seemingly describe something that is imagined: “Plan Miasta B” (City Plan B) “Plan Miasta M” (City Plan M), references to places which we will never know, like a cipher whose key is only known by the artist.

One of her strategies is paradox, false clues, and constant flight from a singular meaning. The motto of “Portfolio,” which is the most private and public gallery, sounds too conventional to be treated seriously: The most important things for me are everyday things

. Ordinary things that float on a screen above a technical drawing, blueprints that are straight and crooked depictions of a very specific object taken from reality. What is “ordinary” within a framework of distinct and unrecognizably contradicting boundaries has to be sought out like forgotten streets on a map worn out by time. For those viewing the websight it is a riddle and mystery, the signature of the artist, which perhaps is hidden in the upper left hand corner of the page. It lurks and skips along bulging stairs (or “steps” - difficult to write about them without using the diminutive) that lead to a house drawn in the very middle of a constructivist composition.

Her drawings are graphic contraband, italics versus logos, and an all-encompassing knowledge of mathematical patterns and literalness. A blueprint which is used by her as an under painting can be compared to hand printed calligraphy that is both singular in meaning and subservient to its own rules.

The italic combines with the concept of a letter,

writes the feminist writer, Anne Marie Christie and has a feminine connotation. Its value has the symbolic quality of the handwriting versus the more popular print letters. Italic is a pause in a narrative, a change in direction.

Italic is a carelessly left behind trace of the writer’s hand (abandoned? lost? unnecessary?), which implies a deeper meaning. The drawings of the artist “are disorganized, not fitting into a structure”, invalidating and undermining everything that is encrypted into petty numbers, ultimately determined.

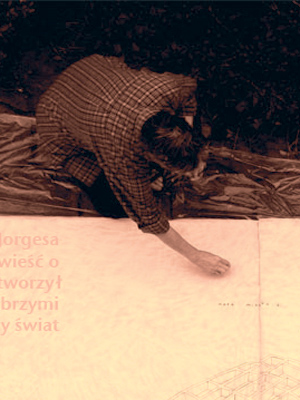

Jola Wagner defines her creation as “tidying up”, in order to understand the world, to tame it and to gain control over it.

While it is true that within the word “ordered” lurks the temptation to “dominate” but it is also close to “spinner”. The word “ordinary” is only separated by a space from the word “mundane” and in the nineteenth century that’s how women artists were perceived, as “SPINNERS of the mundane” escapists from a private reality. Present day female artists merge the boundaries separating the public, private and everyday themes that have ceased to be obscene (meaning behind the scenes) and since the seventies their art has entered the institutionalized world of art, museums and galleries.

The Ordinary as an artistic project.

If we look for it in the drawn diaries, travel journals and handmade atlases of Jola Wagner, we find a carefree “world of wonders”. Drawings – the code of a childhood never lost. Cities or counting out games “ene-due-rabe”, cardboard houses, over which float turquoise elves, paper boats and uninhabited islands on which a portrait of a cat stands next to a palm tree and a pony is frolicking in the sea of grass.

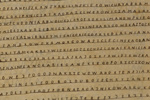

To sketch time, to add and multiply- as an exotic project. To work in isolation and silence which is self written, like “Plan miasta L.” (City plan L.) constructed from words. “Mapa miasta spis ulic: piotrkowskakosciuszkizachodnia” (City map listing of streets: piotrkowskakosciuszkizachodnia) (like the numbered paintings of Roman Opalk monotonously ringing in one’s ears without any hope for change). Tapeworm names that have never met in L. city. Names in an intimate embrace. A city of letters, a city of sounds.

The first of her “diaries” (or rather “counting out games”) put into rows just like in a garden, private symbols in which the easily recognizable shapes of: homes, house hold appliances, animals and people are encoded, she began to put together at the beginning of the 1980’s.

The reality of the marshal-law,

she says many years later its threat shook me in an unbearable way. Thanks to drawing I got a grip on reality, I began to “tidy it up”. For a privacy, which could at any moment become public, unpredictable and degraded, she found a code known only to herself. This code was the only weapon against a fleeting heroic history written by men.

During the period of Poland’s transformation, the elements of excess disappeared from her work. The candy coloured trinkets gave into the laws of a competitive market. Cuddling finds its place on the margin. Archaic maps of “upside down” lands stand at attention, out of the centre of a sheet of paper sprouts a brick wall, meaning a boundary. The world, which could be taken in at a single glance now disappears. The words “hocus –pocus” spoken by a fairy godmother are not understood by developers. Playing hide and seek with a map that turns into an incoherent black and white document. Brick walls “won’t fall” because they won’t touch each other nor try to connect, filled with typographical twists known only to themselves. A labyrinth without an entrance and an exit that serves as a metaphor for transformation.

One can organize the narratives of “indecent” cities, which are falling apart or disappearing, that float or lose their meaning. Jola Wagner chooses a word which resonates like a worn out gear set into motion: she makes inventories of cities, homes, and tableware. With a warm irony she gives us an illusion that we can still gain control over some fragment of an ever-changing reality. The inventory is guarded by nostalgia. The artist herself admits, I associate this word with a storehouse, a pantry or a storage shed at the back of a store. It sounds homely and somewhat archaic as if it was from a PRL childhood, the time when notices hung on the doors of stores with empty shelves read {Cataloguing}.

A word from a long forgotten dictionary.