Apocrypha

I.

These are the words of Qarm of Gabe, also known as El Ri, chronicler of the illustrious Prince Atti-Bus’Dinah.

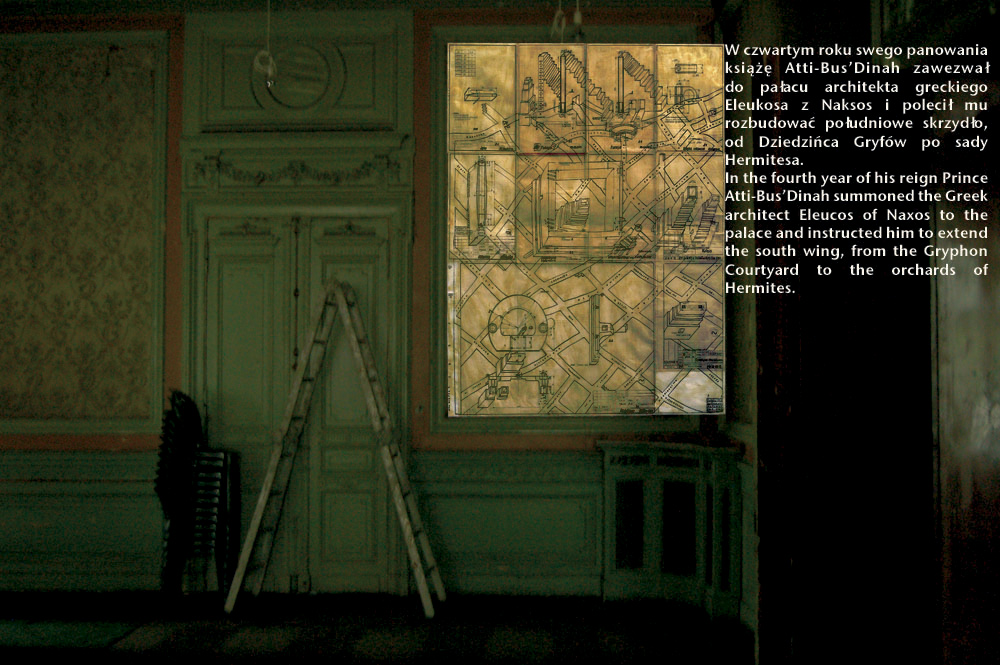

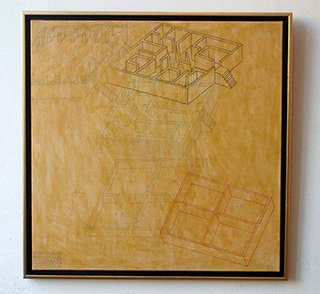

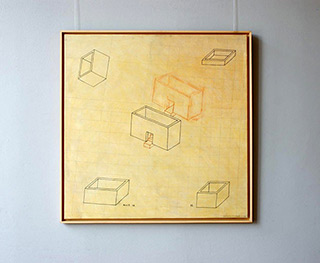

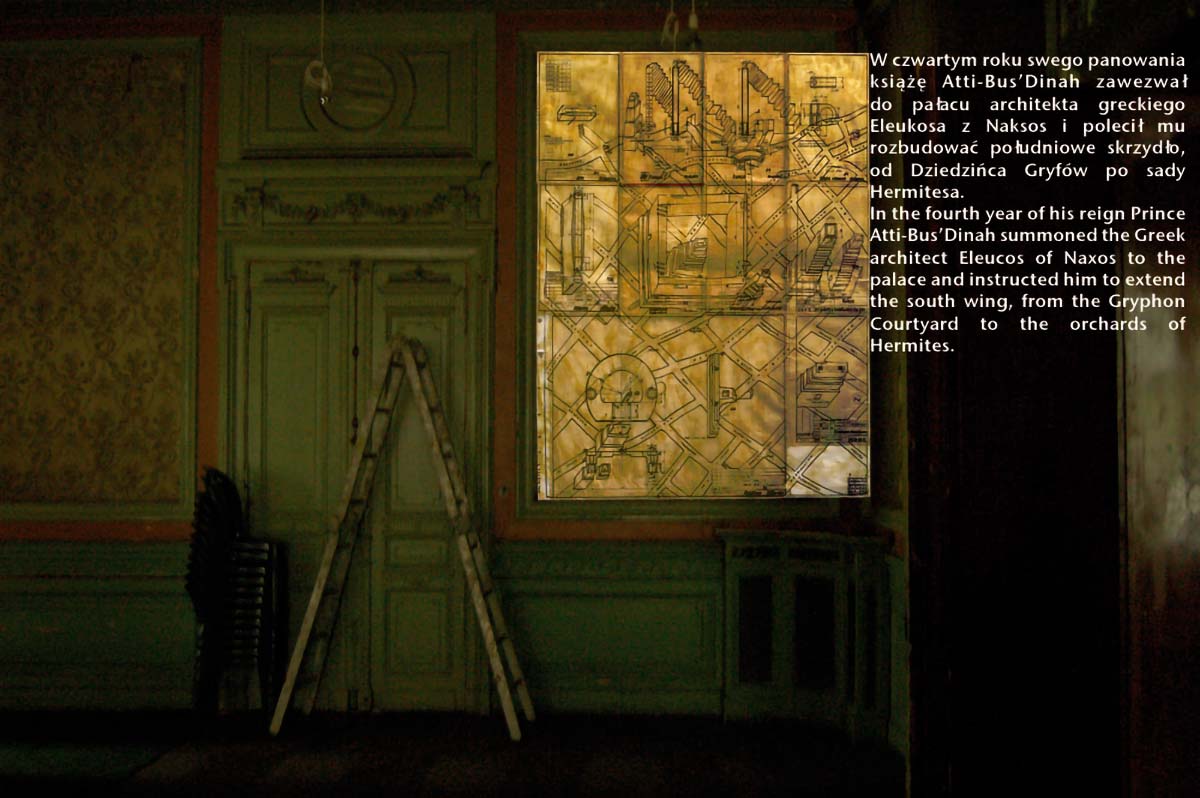

In the fourth year of his reign, in the year 658 since the founding of the city, the illustrious Prince Atti-Bus’Dinah, eighteen years old at the time, summoned the Greek architect Eleucos of Naxos to the palace and instructed him to extend the south wing, from the Gryphon Courtyard to the orchards of Hermites. And then two districts were razed to the ground, a mosque, a synagogue and a small shrine of Mithras, the hills of Saint Jorges were levelled, and a most beauteous colonnade of Parysan marble was erected there, four fountains, two courtyards and a mausoleum to the Prince’s wife who had died in childbirth a year earlier. However, this was not enough for the illustrious Prince, for then he instructed Eleucos, to whose aid he had brought the master craftsman Ibrahim bin Mukap, to broaden the palace on top of the orchards of Hermites and beyond, down the hill all the way to the seashore. There, on successive terraces a series of colonnades, offices and palaces were established, with courtyards and gardens in between them, full of little bowers inlaid with painted tiles, orange trees, pergolas overgrown with vines and cages for peacocks. Yet before these works had been completed, the Prince demanded the demolition of the Armenian district and its transformation into great palace stores: the population were expelled, the streets walled in and the houses converted into granaries. To resettle the Armenians elsewhere, the Prince ordered the Tatar district, Beh, to be rebuilt into a high city, full of spacious tenements, connected by numerous wooden galleries and passages of the kind traditional among the peoples of the east – so that in the new Beh there was enough room for the Armenians and the Tatars, and eventually for the Macedonians too; in the place where they had lived until then a great forum and marketplace were built, as well as a royal bathhouse and stables. And so in turn the palace grew where once the city had extended, and the city where once the suburbs had extended, and onwards, ever onwards.

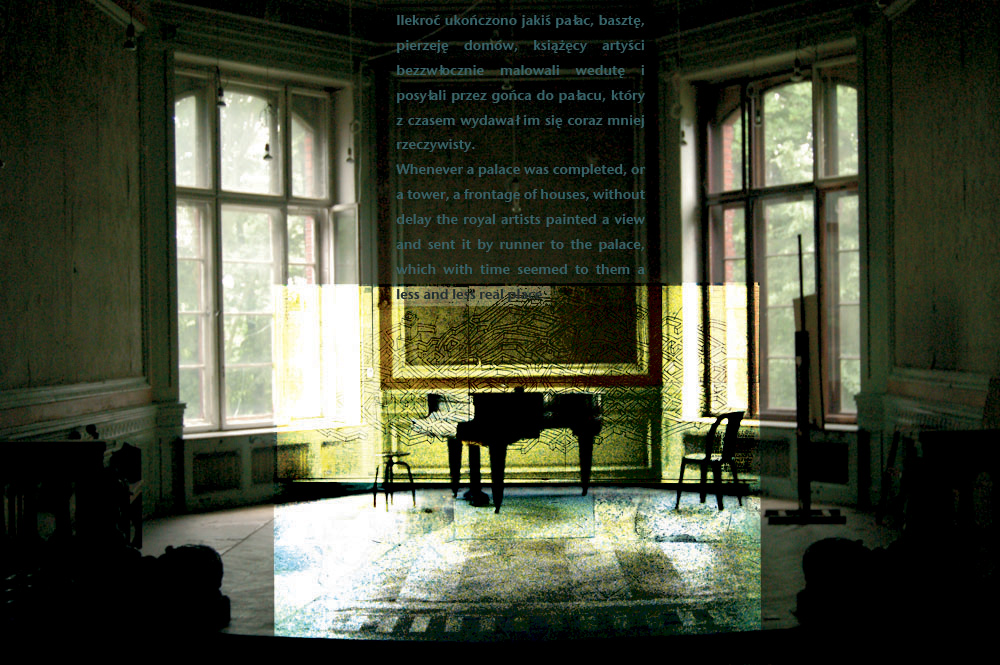

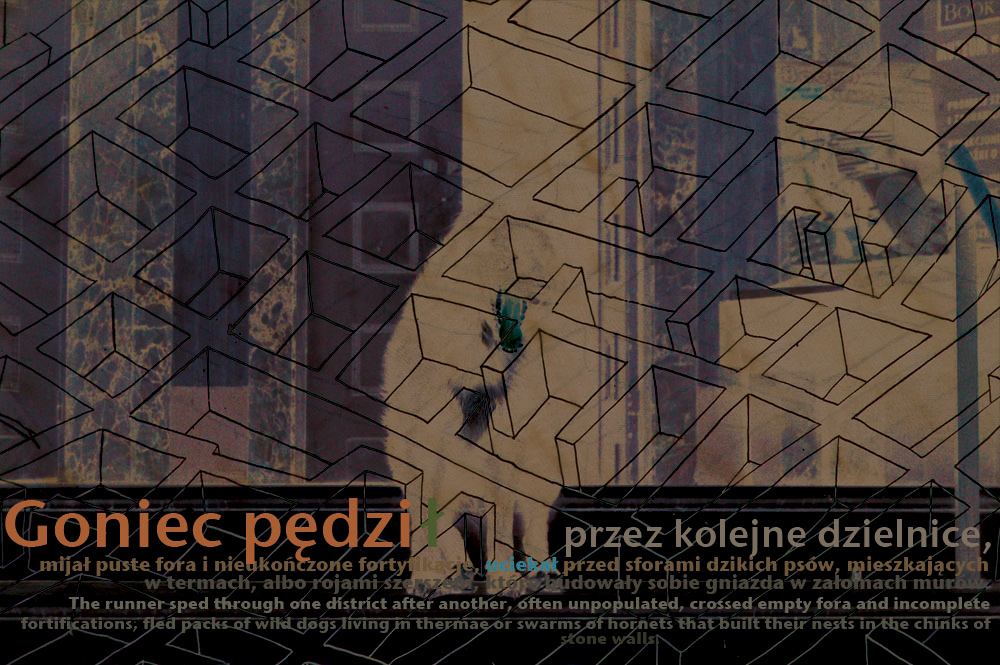

In the beginning the illustrious Prince Atti Bus’Dinah went to inspect each newly erected building, but later he only attended the opening of each new district, until finally, when travelling to the new sites took a week, then two weeks, and eventually a month’s strenuous ride along narrow streets, he entirely abandoned this practice. Instead he limited himself to examining the drawings, plans, maps and etchings that were stored in a great library, erected on the site of the old district of Bah, from where meanwhile the Armenians, Tatars and Macedonians were resettled to the northern edges of the city, somewhere near the Orhan Mountains, for so far had the teams of architects, carpenters and stonemasons now reached. Whenever a palace was completed, or a tower, a frontage of houses or even a plain bazaar full of stalls, without delay the royal artists painted a view and sent it by runner to the palace, which with time seemed to them a less and less real place. The runner sped through one district after another, often unpopulated, crossed empty fora and incomplete fortifications, fled packs of wild dogs living in thermae or swarms of hornets that built their nests in the chinks of stone walls. It took him three months to reach the furthest boundaries of the palace, later a whole year or even two, and afterwards twice the time to reach the throne room or the Great Library, where the Prince was usually to be found. When the runner returned, the boundary was much further away; the nomads who had been forced to settle in new houses spoke a guttural dialect, completely different from that of the citizens of the districts directly adjoining the palace. The old architects and draughtsmen were no longer alive, so their sons received the runner, handed him the latest sketches, drawings and etchings and, having allowed him a day and a night’s rest, sent him on the return journey to the ever more venerable Prince.

Once they reached him, he drew drawings of districts that only their grandsons would reach.

II.

These are the words of Atti-Bus’Dinah, the Prince.

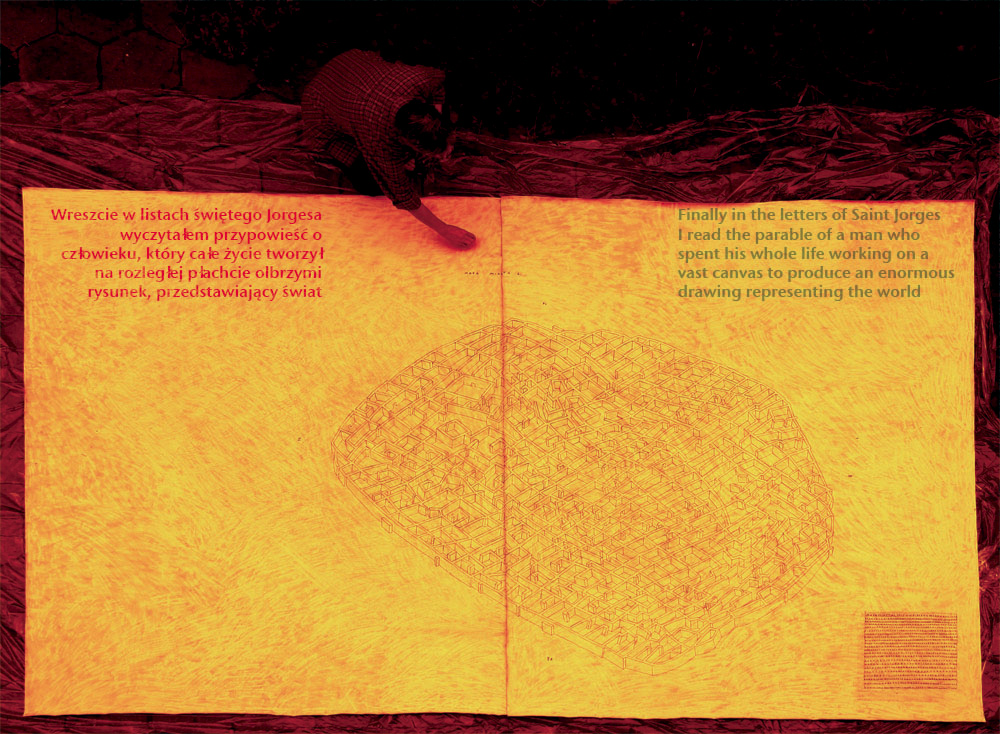

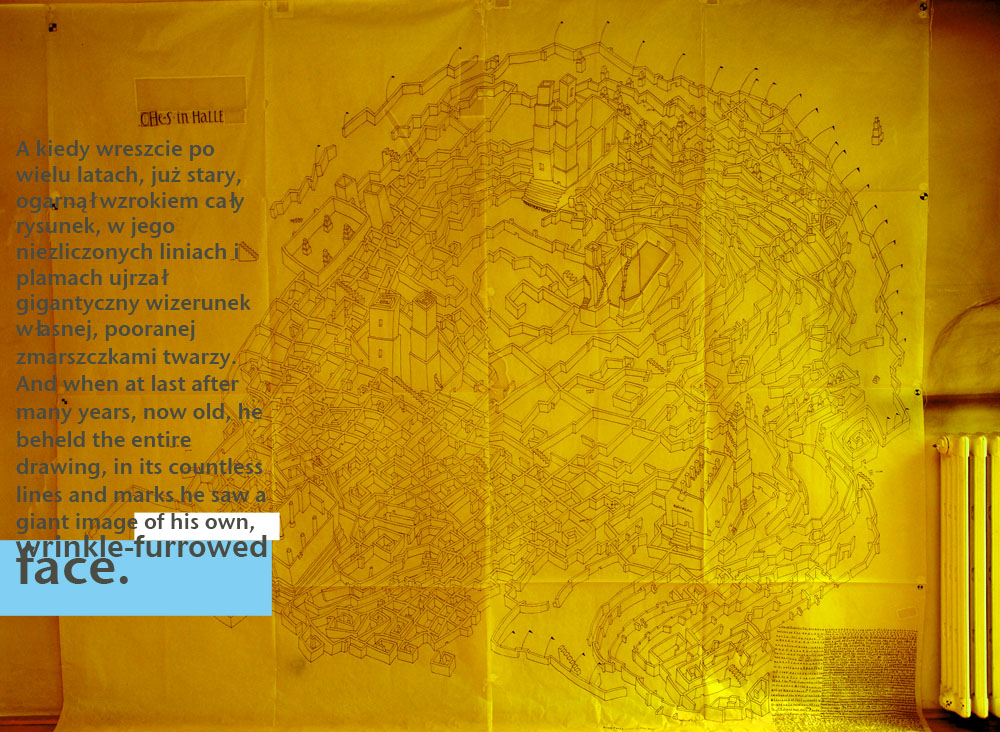

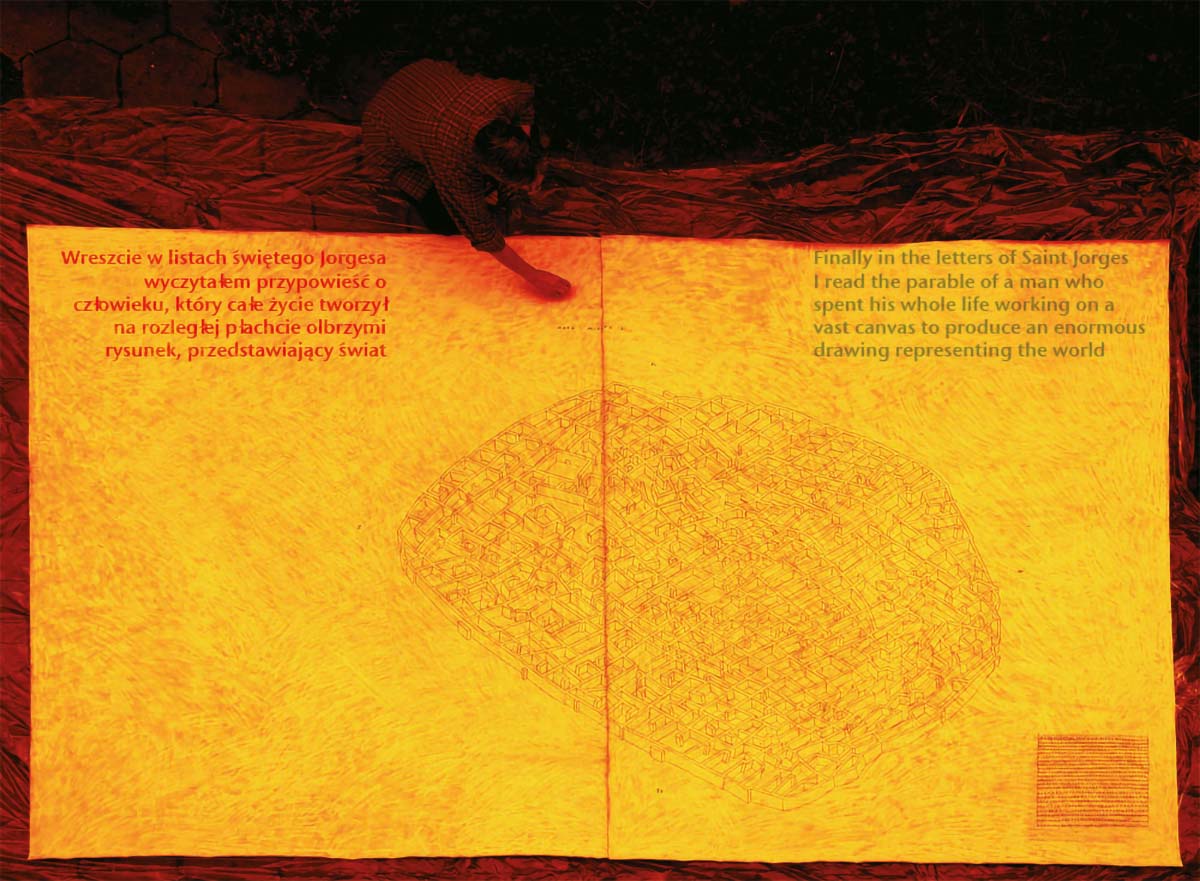

God gave me a long life and many years to raise a city that grew during my reign from the Porphyreum coast to the Orhan Mountains, and from the Microcephalos Desert to the banks of the River Gehr. In the beginning I built to make the city more beautiful, the palace more spacious and more impressive, the gardens closer to the image of paradise, the temples an even more perfect tribute to the Gods of East and West. Later I built to make the people happier: I ordered hospitals to be built, and aqueducts bringing pure mountain water, sewers to be laid, and public parks and gardens to be designed; for the monks I erected spacious monasteries, for the wanton ergonomically planned red-light districts. Finally in the letters of Saint Jorges I read the parable of a man who spent his whole life working on a vast canvas to produce an enormous drawing representing the world: land, water, cities, animals, mountains, forests, deserts, all incredibly beautiful and precise. And when at last after many years, now old, he beheld the entire drawing, in its countless lines and marks he saw a giant image of his own, wrinkle-furrowed face.

When I sensed that my days were coming to an end, I decided to travel to the far ends of the city and examine for the first and last time the impressive dimensions of my work. At first we rode through wealthy districts, and were greeted by guilds of haberdashers, dyers, mercers and spice merchants, felt-makers and coopers; flowers were thrown under our horses’ hooves and we were sprinkled in aromatic oils. But the deeper we went into the outlying districts, the more mistrustfully we were regarded. By Nodoso stream some youths threw stones at us; one day when I awoke before dawn, there was an arrow sticking in my pillow that had passed through the canvas of the tent and pierced the very centre of the sun embroidered in golden thread. Just before Beled Nubian bandits severely wounded one of my generals; beyond Beled it was even worse, because no one understood our language, though we had not yet left the walls of the city and were still riding along the streets of this same metropolis. Not even the highest peaks of the Orhan Mountains, from where I intended to view the entire city, were yet visible above the rooftops.

My journey was to run to an end in the Kirig district, occupied by the Houndheads, where my heart refused to do my bidding. I was laid in a splendid tent, blood was let and herbs were brewed, but gradually I began to realise that it would not be my fate to see the city from a suitable distance, it would not be my fate to find the features of my own face in the lines of that gigantic construction.

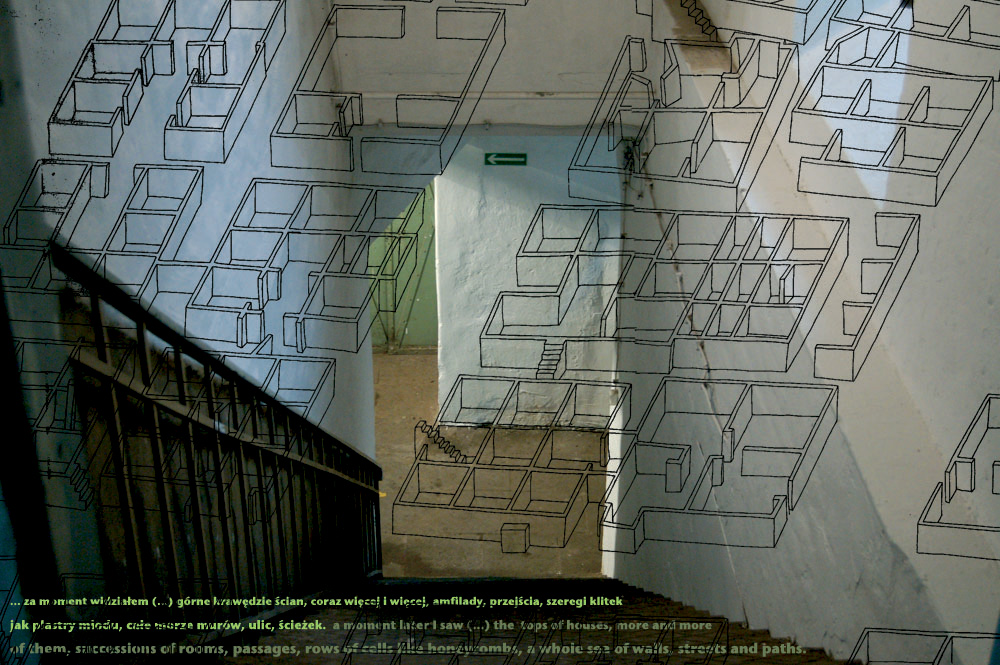

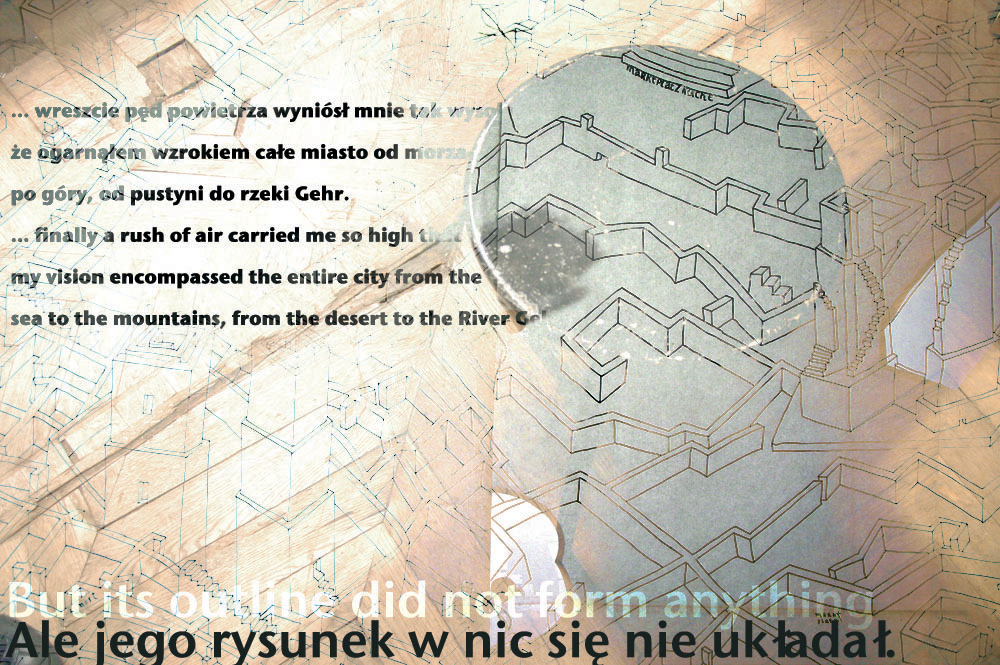

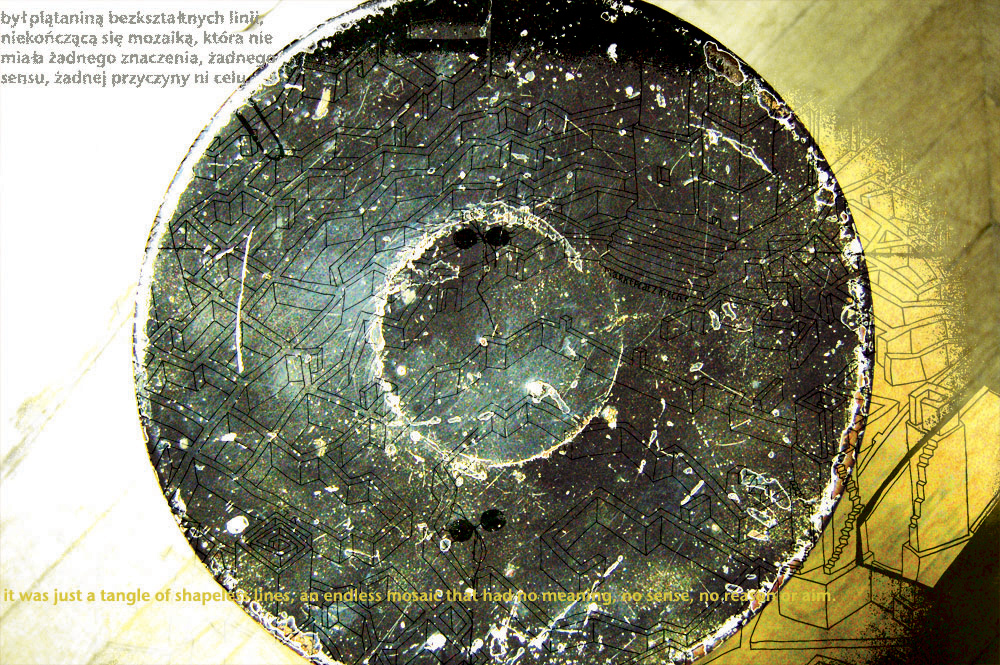

And just then Satan sent two wandering Arab scholars to meet me, who were on their way to the Prince of Dhera. Having heard from the courtiers the intention with which I had started my journey, they promised to sell me the opportunity to see the city. The sum they demanded was not excessive, but in any case everything becomes cheap in the face of death. From their saddlebags they extracted a vast bladder made of glued Cipangong silk, placed it in the middle of the square, tied it securely with great ribbons to all four legs of my bed, and then ordered a large bonfire to be lit to heat the air that was to fill the bladder and raise me aloft. And indeed, after a few moments had passed I felt the bed shudder, and lo, very slowly I began to rise, first to the height of a hand, then an elbow; a moment later I saw the courtiers’ faces, then the crowns of their heads, the windows of rooms on the first floor, entirely empty, then the equally empty windows of the second floors and ruined attics, finally the remains of roofs and the tops of houses, more and more of them, successions of rooms, passages, rows of cells like honeycombs, a whole sea of walls, streets and paths. I rose higher and higher, until I could see almost every district, but it was still too little; finally a rush of air carried me so high that my vision encompassed the entire city from the sea to the mountains, from the desert to the River Gehr. But its outline did not form anything – it was just a tangle of shapeless lines, an endless mosaic that had no meaning, no sense, no reason or aim.

I passed the first layer of clouds, and the air became colder and colder.

III.

These are the words of Professor Albrecht Rosendorfer, archaeologist.

At first we took site 3502-F to be the remains of the Roman colony of Tuginium which, if one is to believe Aecius of Mediolanum should lie in roughly this area. However, we had come across the city of Buz, which was the capital of the Persimond principality, and which enjoyed its greatest development in the reign of Atti-Bus’Dinah. Following the death of this ruler, for unknown reasons the city fell into complete ruin.

Relatively speaking, the centre was the best preserved area; the German and British team discovered the ruins of a great palace and library, several temples, thermae and a forum where there were many valuable antiques, including mosaics, bronzes, and several late-Roman sculptures. Further on, our mission discovered housing districts made of fired bricks, some equipped with sewage systems and surfaced roads; but the further we moved away from the centre, the greater our amazement – by and large, the city was infinite. The further from the palace, the weaker the materials used to build the walls. The desert sand had preserved stone, brick, wood and papyrus superbly. At the foot of the Orhan Mountains we discovered an entire district woven from grass, composed of light partitions and painted cloth. These are endless successions of small rooms leading to courtyards, from which in turn run narrow streets with frontages moulded out of honeycomb, slats and volatile sand; the streets converge on a large square which is built out of silk cocoons, joined together so skilfully that they retain their original shape to this day, conserved by the blazing desert air.

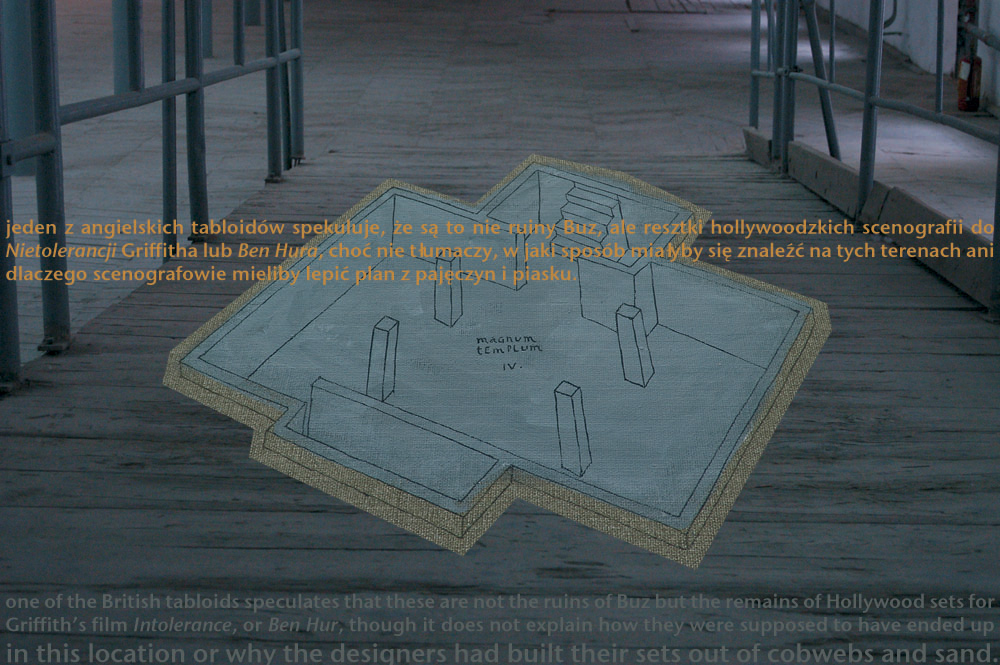

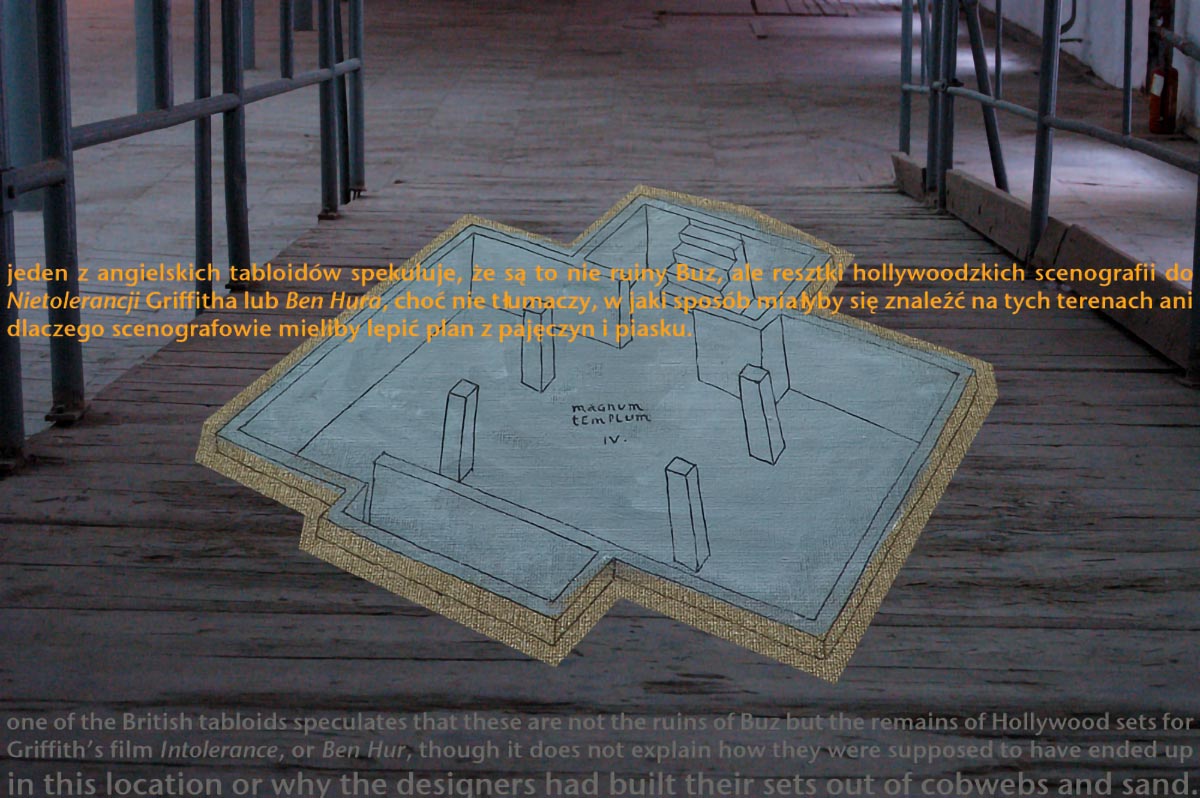

We do not know what the purpose of this ghost town was; one of the British tabloids speculates that these are not the ruins of Buz but the remains of Hollywood sets for Griffith’s film Intolerance, or Ben Hur, though it does not explain how they were supposed to have ended up in this location or why the designers had built their sets out of cobwebs and sand. Documents from the palace library of Atti-Bus’Dinah would certainly be a valuable guide to discovering the history of this place – unfortunately, unlike the light walls of the houses, situated at the foot of the mountains, as soon as they are removed from the sand the papyruses crumble almost without trace, leaving nothing but a handful of reddish dust and a sad, acrid smell.

Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones