On Adam Patrzyk

I.

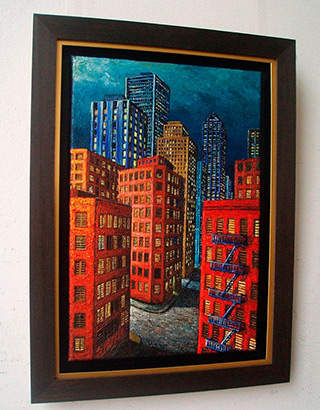

Our fascination with the world portrayed by Adam Patrzyk comes quickly, and it brings with it a question: Should we be wary of these places, or should we be drawn to them? This is magical painting, which means that it arouses a vague desire to enter the paintings, to reside in their spaces, without knowing—not right away—whether for good or ill. As is often the case, the first thing we experience is a sense of déjà vu: we see what, tentatively, we already know has been painted and told by others before. We peer into Patrzyk’s cities, landscapes, and houses with our baggage of associations and analogies, and with the impression that we have been here before, but then we notice that our knowledge is becoming alienated, fading, and breaking down under the pressure of tremendous color, color that at first may even seem furious or dangerously hot, and under the weight of identical forms, which hit us like notes in serial music, turning time into an echo: a closed, isolated, self-fulfilling whole, liminal, beyond our usual, chronological duration. In several of his paintings, the city quite simply becomes a gargantuan instrument, with thousands of windows and lanes that form colorful keyboards, which play the same enchanting theme over and over again.

You can get lost in a Kandinsky painting,

a reviewer of a Paris exhibit recently exclaimed, just as you can in the woods. And one should not deny oneself the pleasure.

To get lost in a painting is a lovely criterion for delight. But in Patrzyk’s paintings, whose colors are just as intense as in Kandinsky’s, we can neither stray, nor lose our way. We cannot poke around as we might, say, in Kandinsky’s paintings. Nor can we even be sure that we are permitted into these territories, these rooms, these streets. Who is inviting us here, and to what purpose? And if we decide, bravely and perhaps a little brazenly, to go through with it, then blissful obliteration will be neither our risk, nor our reward; we will go no further than Patrzyk’s geometry, which is where we will find ourselves, plain as day, stupidly visible, deprived of intimacy. And we’ll have to make do with that.

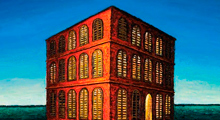

One arrives, therefore, with a tentative understanding (the urban landscapes, with their skyscrapers, would suit the triumphant opening of Woody Allen’s Manhattan, with its Gershwin soundtrack), yet from one painting to the next it advances, or rather withdraws, toward astonishment. This is not a matter of intellectual or sensual incomprehension, however, but rather of a primal or suddenly exposed state of life rising before our very eyes, contrasting with the civilization presented here: that rudaceous, almost igneous texture of the streets, these bumps and streaks in the floors, walls, and earth, a bit like the surface of the moon, or like the first vibrating atoms just as they are joining together. It is difficult to say anything about this geological substance, which reaches even to the interiors of apartments. But not because we are crossing a boundary beyond which some inexpressible, fantastic world unfolds, but on the contrary, because something rather old opens before us, something which we have forgotten in our very own cities: the porous, grainy, coarse composition of existence, woven out of colorful particles, the very core of matter. It may not be pretty when exposed so directly, and yet it is alive, in motion, sometimes aflame, in fact waving, as if someone were swinging these picture around, and it is only here and there that something—what just yesterday had been lava—now cools down. A core formed in a kind of primordial beginning, as if just excavated, or else like a freshly woven carpet, in which we encounter hues in swollen, accelerated gradations, or else in sharp, yet complementary, oppositions. Then it may seem that the creator of this world has left us the building blocks of houses at just the moment when chaos has stopped coalescing into form. The blood-red, calm blocks are beaten straight into the ground, like hand-stamps into an original document. Thus our hesitation: What to hold onto, what to approach? To move toward the decorations offered to us, or toward the bare earth? Or simply to trust their strange symbiosis?

II.

Déjà vu. Melancholia, for example, is one of the enticing points of entry into Patrzyk’s work, but it is not a point of departure, for at a certain instant we lose its trail. Thematic and formal associations with painting nowadays regarded as melancholic—with the canvases of Giorgio de Chirico (stark contrasts of light and shadow, an urban “Italian-ness”), with Hopper (empty streets, numerous windows, squares of light, an urban “American-ness”), and perhaps even more distantly with Delvaux (through a certain affectation of urban décor)—are no doubt inevitable, though such comparison fails to account for that other emptiness, crucial for Patrzyk: the emptiness of a city without people, the emptiness of interiors without people. This has a different character, and it exudes a different mood than Hopper’s desolate cobblestones and hotel rooms. We will therefore have to dispense gradually with analogies, since in Patrzyk’s paintings there are no excessive privileges for mankind, including those that flow from the mournful relishing of melancholia, from Sunday-morning solitude, from reverie behind a café window. Before these windows, in the glare of sunlight, one finds no American woman standing, nor is there a shadow cast on the pavement by some young Italian girl urging a hoop forward with a stick, which is all the more reason for us to expect no allegories petrified in the middle of a city of portrait statuary. Furthermore, it isn’t certain whether the gaze from which these pictures arose is that of a human, melancholically pensive eye, or rather a sensorium that responds to color, light, and motion.

With Patrzyk, the question of the “I” seems especially discomfiting. Who feels here, and what pains him? Or pleases him? Who turned on the lights in the windows, who pulled down the blinds and shades behind them, closed (and later threw open) the shutters, as though in each place, behind every pane, some show had just ended? And maybe this is just an illusion, and the windowpanes merely draw in the light from outside, which illuminates them, but sometimes breaks through with a sort of immaculate touch? Working like a delicate, artistic neutron bomb, or like an epidemic of method, Patrzyk has delivered buildings and bridges—infrastructure, to put it managerially—and removed (into some deep recesses, behind curtains) living beings. This absence strikes and disturbs us, but maybe it isn’t at all as dramatic as it initially seems. For isn’t it true that when we snap a picture we don’t wait for the people to vanish from the field of vision? People and animals, or plants, for that matter, wouldn’t even fit in here formally, anyway: their shapes are awkward, ephemeral, and geometrically uninteresting, no good for painting. Thus, if something of a melancholic aesthetic breaks through in Patrzyk, it’s in the very organization in places. The painter’s world is thought out in just this way, more geometrico, through acute angles, through certain repeated forms, a doubling of decisions, a copying of masses. As in the case of de Chirico, we may historicize this inclination toward the constructive and the geometric, as well as the heightened use of perspective, to the Neo-Platonic Renaissance tradition (as Erwin Panofsky analyzes it in his studies of Dürer), which placed the arts of geometry and mathematics under the sign of Saturn. But it quickly becomes evident that, there, geometry and mathematics served above all else to report on the weakness of the human mind, conscious of its own cognitive limits, helpless before the infinite, whereas here they are frenzied, lyrical vehicles of the imagination.

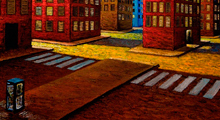

In Patrzyk’s canvases, it is the perspective that is peculiar, inventive, ardent, intense, as if the air that is forced into it, hardened within it, had the power to strike us dumb, a perspective at times even bordering on (as it does in Bathroom)—though prudently never falling into—dizzying anamorphosis. Peculiar, too, are the vantage points, usually positioned at some height, ostensibly on the highest floors, or else somewhere under the ceilings, or rather in the air, now higher, now lower, rarely quite low—these are the vantage points of Batman as he glides freely over the earth and looks for a good view. Our gaze dives downward, extending and clarifying the field of vision, which fosters an odd, methodical pedantry. No line here is left to its own devices; no possibility of casting a shadow or reflecting light is neglected. Such paintings as The Corner and other urban tramway variations rather seem like paroxysms of precision. The correspondences between all the horizontal lines—the lines between floors in the buildings, the rails on the ground, the tram wires overhead and the shadows they cast, swallowed precisely by the entries to those buildings—are extraordinary. This is a realism of the insane, but also of fathers and children setting up stations and running toy trains together on the rug.

Repetition and perspective broaden this world and, at the same time, miniaturize it: paradoxically, the successive lines of trams, bridges, or windows do not make these places larger, but instead heighten their toy-like intimacy. While the cities seem to proliferate boundlessly in this way, through the cloning of their components, and while they are most often seen at the waist, in the middle of a fragment, and we cannot see their borders, they nevertheless cultivate their own theory of relativity. We are stuck in their single, modest little portion, yet we are almost always downtown, which intensifies the impression of symmetry and soothes the disquiet brought on by repetition. The interiors, like those of libraries or quasi-churches, spread out into a calm infinity, gently copying out their scrolls; the arches in the bridges that proliferate over the river, fragmented ad infinitum, are woven precisely into the air. The same keeps adding to itself. From this we get rhythm.

In considering this repetition, this pathology of forms, their metastases arranged into a spatial, spacious echo, one thinks also of Piranesi, of his famous Carceri prison drawings, immeasurably intriguing for the imaginations of opium-smoking poets (de Quincey, Baudelaire). Only theirs were Romantic imaginations, fascinated with depths, ready to lose themselves in nothingness and the Absolute, looking for a way out down below, looking for a heaven—or an abyss—beneath the earth. From the repetitions that disturbed them—the levels of the prison, stairs that come one after another—these imaginations longed to forge a path that would exceed the imaginable and cross beyond the existence of the here-and-now. Imaginations that sometimes, terrified, discerned that they were stuck in an unbounded prison, like living flies trapped in amber. As Victor Hugo called it, “the black brain of Piranesi.” In Patrzyk, the impulse toward infinite motion is almost always horizontal, less—or not at all—gloomy, relentless, and hysterical, more formal than “philosophical”; the Romantic dilemma of imprisonment/excess seems entirely alien to him. One may sometimes imagine that these long corridors in open perspective are the interiors of fiber-optic cable or of the trails of color one travels, enchanted and without purpose, along a prescribed course, similarly to the way the shadows of people or pockets of air move along, tirelessly carried in trams.

III.

We do not know what really lies in those entryways that sit open like mouse holes from Disney cartoons. We don’t know what the real source of this light is: the sun or the moon, the gloaming or some cosmic reflection, or rather a humungous flashlight, since the shafts of light often branch out from the side or from below. We don’t really know what time of day or year it is. We don’t know where these trams are gliding so urgently. And what’s with this urbanism without the urban, without stores, stands, and islands of green? Why is it that, looking at Patrzyk’s paintings, one feels like returning to Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities? Kublai Khan does not necessarily believe everything Marco Polo says when he describes the cities visited on his expeditions,

in William Weaver’s translation. Yes, it’s hard to say: we sort of believe what Patrzyk says of his expeditions, but to an even greater extent we do not. Patrzyk’s art inscribes within itself a fundamental ambiguity, the kind we encounter whenever we contemplate the work of the most interesting realist painters, who ask to be read, especially when the interpreter puts the screws on, as metaphysical painters. When Hopper says, What I wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house,

we believe him, and at the same time we know what’s what: his seaside rooms, with their sunny squares on the walls, are immediately situated for us beyond realistic reproduction, in the register of ultimate places. In Adam Patrzyk, a delicate boundary also runs between these two worlds, the “given” and the “made”; nearly every certainty appears to offer its own obscure opposite, a more or less realistic façade concealing God-knows-what, a more or less “normal” bathroom for unfamiliar ablutions. That which is singular still speaks of itself—sometimes, both here and there—realistically; that which is doubled and multiplied opens a gate into pittura metafisica. These cities, like those described by Marco Polo, exist according to their own hermetic principles, which determine their singularity and distinctiveness. Sometimes, at first glance, they even give the impression that Patrzyk found them like this, but we—Kublai Khans settled in the poor, deteriorating modernity of Warsaw, Lodz, or wherever—suspect that someone is making these principles up and telling us about them. Who ever heard of a city where you don’t have to wait for the tram? All the more reason that our fascination does not wane. Only in Marco Polo’s accounts was Kublai Khan able to discern, through the walls and towers destined to crumble, the tracery of a pattern so subtle it could escape the termites’ gnawing.

How, then, can we grasp this “pattern so subtle,” this “invisible” city, the space painted/told by Adam Patrzyk? Grasp it as though in hand, grasp it entire, for there exists a temptation, or rather a need, to describe it at one go, to gather it in as a uniform, separate vision. Because, after all, Patrzyk seems to be painting a single, cohesive civilization, closed and sealed, like the civilization of the Incas, of the islands of Bali, or of Stonehenge, with its boulders standing upright. The viewer has a difficult choice to make: to discern in this artwork what is first of all a creation ex nihilo, or rather to look less globally and turn his or her attention to process, to an experiment with found space? Should we tune in to the monologue of the imagination, or the dialogue with real places? Should we aim for a vision more cosmogonic and natural, or more philosophical and social? The present text leans more toward the former.

Amidst the shafts of light falling theatrically from the side and from over the ground, among the shimmering webs of brightness, stage sets take shape, often painted in contre-jour. Patrzyk’s brush is slightly decorative (one could weave ornate fabrics from those colorful braids), a bit pompous, ever-so-slightly comic-bookish; he is led by a minor expressionist excess, which heats the particles, but which presses them into a precise jigsaw puzzle. It is difficult to shake the impression that this perfect, puritanical table puzzle was actually excerpted from some larger conglomeration called universum or universe. But how it became so distanced from the universe, or what impelled it to leave, remains a mystery. What moods accompany this creation of unlimited liminality? This agglomeration of blocks of matter on the margins of life, cobbling them together into one transparently organized, if dense, mass? Sometimes, staring into these paintings, one sense that a debt has been inscribed within them, a debt to an evil exterior, a kind of burden, of that which has not been quite grasped in them, the radiation of that other, distant, perhaps alien world. But above all—and one probably has to aspire toward this feeling—we find the species of happiness that children attain when they succeed in finding a hiding place inaccessible to others, their own den in a nearby wood, their own tent in the garden. Or else when they settle down under the adult table. Or when they pour their Legos on the rug and build the world from the ground up.

The point here is not to completely disarm Patrzyk’s artwork of the vague menace dreamt in the background of many of his canvasses. At any rate, the longer one has to gaze into them, the more apparent their warmth becomes. But one must speak of the simultaneous furnishing of the chosen place, the substitute place, utopian, idyllic. The kind where time is undone, is ordered to exist in eternal repetition, while geometry has the freedom to create angles. Repetition is always double-edged, it is a delight and a curse at the same time, both rhythm and blockage. Usually it is oppressive, though not in a utopia or idyll, where it guards us against the fateful succession of passing moments, dams the flow or degeneration, and becomes a creative, intoxicating, in no way imprisoning principle. In this unsweet idyll of Patrzyk’s, which has nothing in common with pastoral bliss, in this happy exile, the place of one’s own is furnished with microscopic, meticulous attention, showing the dreamt-of possibility, that by which space might be revealed if it were, at the same time, color, shape, and music. These landscapes hold something ideal within them, as in the so-called ideal-landscape paintings of the eighteenth century. One must assimilate them, reach their good side: beside the acuteness of the angles, the whole urban enormity, the indefinite atmosphere of twilight, one must find their snap and good cheer. Because these caterpillar-trams, gliding and sliding in all directions, these firefly-trams, together with the houses, viaducts, and windows arranged in a mathematical order, start to create a rhythmic, harmonious whole, as if the city were performing a ballet, delicate, slight, but noticeable: some of Patrzyk’s paintings dance. And there are painting-scores, like Zone, which we can read as an audio recording at a different pitch; here, stability vibrates as well and remains under pressure. This filling, dynamic density of events, squeezed into one moment and one place, into one three-dimensional web, this density of material being, is lovely, genuinely artistic, and creates a peculiar—the word needs to be repeated—harmony.

Colors and contrasts also belong to events. Speaking tautologically, Adam Patrzyk is very painterly (as is said of certain writers, that they are more literary than others). He has a generous hand, but not a profligate one; he seems to maintain a perfect balance between discipline and temperament. His colors are not simply there, but occur: some pulsate, while others collaborate in parallel bands, in transitions from warm to cold, contrasting but complementary, life-giving chains, an untouchable mosaic of shadows and colors. The contrasts between brightness and shadow, which seem so sharp, even hostile in their emphasis of sudden areas of darkness, turn out to be benevolent, holding the urban landscape together more than they break it up. In the magnificent Passing, the areas of light and shadow complement one another (one may think of a ying-yang) in a single, full, perfect, mildly intoxicating form, which we can contemplate for its superlative—for it is pure—pleasure.

IV.

Is it therefore possible to impart some concrete significance to this form? To say where it comes from, where it is going? We can try, and we want to: Patrzyk’s repetitions set our minds on infinite resonance. Once we step into these repetitions, however, it is difficult to halt their echo within us, ultimately to come to rest on a single threshold, on a meaning we have taken hold of.

Sure, an echo is always a response, the repetition of an initial voice. How, then, can we find that initial voice, the primal idea in Patrzyk, and what should it look like? A contrary impulse, or desertion? It doesn’t matter; in the world of the echo, let’s hear only echoes; in the world of colorful bands, let’s flitter among the bands and savor their recurrences. The painter’s imagination—certainly not right away, but after traveling some distance—slips out from all references to remain alone with its walls, trams, and light. Interested exclusively in forms, the juxtaposition of masses, the companionship of shapes and colors, it now paints only its own destiny (and destiny is the instant when we no longer seek out meaning), the series of houses, tracks, windows, the calm sky, the bulging, blood-red floors, all inscribed into the cycle of return. As someone once put it, “it paints itself a way out,” a way out to another—not its own—world, to what is surely the world we all share. But it has no intention of coming out.

In this imagination there is something, one might say, animalian. It is attracted to light like a moth, irresistibly, seeking it out in the entryways, recesses, windows, and summoning it from an archway, and seen through a scope light becomes a ball, a cosmic balloon, and seen through a crack light becomes a warm ribbon. This imagination lures light from the walls, through open doors, and from the city, through rectangular gaps or panoramic panes. The houses are warehouses, storerooms, and mirrors for light, or else, as in the case of the “Italian” city, only facades and set-pieces that illuminate the path toward light’s plenitude in the windows. Light in interiors, like a concert stage underwater —this is the impression we get, as in Intermission, a wonderful Atlantis of violins—coalesces into pure extract, if we can imagine an extract or liquor made out of light. Thus the trams appear, first of all, to move, to cast patches of light on the ground. Patrzyk makes of light a game of open/closed, he coaxes it out of hiding, locks it behind barriers, hides it in darkness, all to make it more powerful; sometimes he lets it out in a room, other times he blocks its path, hides it behind walls, where it lingers and waits. The light seems to be the most powerful—and here, perhaps the only—spiritual presence, the pneuma that joins all places together. It supplants man, rubs against the strings of instruments, flashes beneath the water in the bathtub. It embalms these landscapes, this peopleless interiors, and fills them with a solemn concentration. If one were to add a single gesture to all these house-boxes, one great stream of light might burst into the air. So it does not matter whether anyone is going to enter that bath a second time, or reach for that violin again, or lie down on that bed. There is no human history here, no activity, no plot, since these are a momentary disruption in the free flow of light,

as Andrzej Stasiuk writes in Dukla. There’s no point in asking questions about human habitation, why it has been suspended, when it will resume and end its quarantine. It’s lurking somewhere, holding its breath; its presence is spectral, suspended, slightly palpable. For the time being—for eternity?—Patrzyk has cloaked it in invisibility. He’s pressed pause. And a pause can be a powerful force for a free imagination. Thus he has tested whether a world in pause, without us at its center, is also imaginable. It is, and here’s how.

* * *

In my apartment, on the longest, completely bare white wall, there is a Hopper painting. Neither an original, nor a reproduction; it doesn’t hang there so much as it appears. On a sunny day, before noon, it issues a warm, yellow square and lasts, shifting ever so slightly, for an hour or two. I can stare at it forever. Now, in the evenings, I look for an Adam Patrzyk painting on the wall. It is beginning to arrive: the creamy yellow burrows, the flecks of glare forming small archipelagoes and a rash-like glow on a dark background.

The title by editor