Lurking, frozen. About the newest paintings by Joanna Mieszko-Nita

If you took the whole colour out of Nikifor’s watercolours, you would be left, as it turns out, with exactly half of his artistic result. According to other “calculations”, one part has already been taken by Edward Dwurnik, therefore, this would mean half of the remaining two thirds… This, in short, presents an aspect of the Polish contemporary painting, meaning that very few are bold enough to reinterpret Nikifor, as the language created by him does not suffer double talks and calls for a transformation.

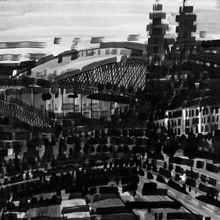

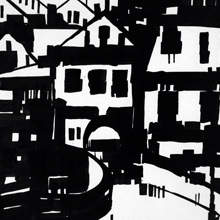

In Książnica Pomorska in Szczecin, an exhibition of paintings by Joanna Mieszko-Nita can be seen, entitled “O Szczecinie” [About Szczecin] (from 2 to 28 September 2016). In Sala Pod Piramidą [Hall under the Pyramid] there are the latest large format acrylic paintings as well as smaller works in ink. The point of origin of these works were so-called naive paintings of the famous Lemko from Krynica. Easily recognizable are the well-analysed Nikifor’s stylistics and some directly transferred solutions, such as the wood of needles, drawn with a steady slanted grid. Here, instead of considering the Krynica source and at the same time, the great inspiration for those canvases, it is better to analyse at the crossing of which aesthetic themes they are located thanks to the simple cutting out of colour. This will be mainly the topic of black and white as such, the topic of black and white photography and the painting landscape.

The black and white forms in paintings by Joanna Mieszko-Nita spread visible forms of light. How much do they have in common with the actual identity of the presented places, their history, individual nature, name? Little, it seems. It seems that all colour synthesizes in full light or is lost in darkness – symbolically expressed with black and white. The universal order and cohesion of these two opposites are best told by the Eastern Taoist philosophy, in which the eternal and unnameable power called Tao, which, however, is no power as it cannot be named, transcends the Universe (the path of nature) and the human life (the path of man). In the Yin-Yang symbol, all opposing (dualistic) characteristics of the visible world complement each other, they cannot exist without each other. And so, passiveness and activeness, darkness and light, masculinity and femininity, although balancing each other, all include a piece of their opposite. Based on this relation, among others, but not only, in psychology, defined is the possibility of understanding and spiritual affinity between a man and a woman, known to usually remain on their separate planets. Within the framework of visual arts, the conclusion would be that the painter, by reducing colours on their palette to mere black and white, turns their eyes away from the reality perceived by senses, the whole fantastically colourful excessiveness, the deceiving overflow of vision. This means the priority of a method in the technique and the reason in perception, a simultaneous analysis of elements of the perceived landscape and the composition, as well as consideration of maintenance of coherence in the plane. Coherence and order are not necessarily the result of just the adopted method of constructing the painting using spots laid with a broad brush in a little varied manner, in turn vertically and horizontally.

It would seem that these paintings are like notes, although fully formed and completed, taken from the “painter’s path”, which, following their internal artistic intuitions, they travel aware of the direction they should be taking. They chose the Tao road and accomplish a synthesis.

Due to the use of blacks and whites to create paintings, with just one or two, but no more than three steps of grey, the connection of these paintings to black and white photography should be considered. The paintings seemingly are not in any direct relationship to this tradition. It is not so that every black and white painting implies the need to refer to the art of photography. Numerous examples can be given when photography clearly inspires painting expressions, such as for example old photos powering the form of Paweł Baśnik’s paintings.

The second reservation has to do with the monochromatic painting, which in works by Willem Claesz Heda or other Dutch masters of the golden age of the 17th century is something different than the contemporary black and whites, born – like the works by Franz Kline – from a merger, one could call it a non-historical one, of the graphic tradition and an abstract gesture. This would create something rather opposite to the monochromatic method, that is a colour impression made of pigments reduced only to blacks and whites, and not a suggestion of a “black and white” painting using a more or less limited colour palette.

Here, it is worth to consider achievements of contemporary black and white photography. It is a paradox that theorists call it saturated with colour and having a colour intensity not found before. From the photographs by Edward Hartwig, Janina Mierzecka or Jan Bułhak, mostly so-called bromine ones, the contemporary art of photography has gone a long road and is now present, for example, at the intersection of communication and publishing technologies, ideology, politics and history, perception research, etc. This was clearly shown by the exhibition “Inżynieria obrazu – (re)aktywacja fotografii” [Image Engineering – (Re)Activation of Photography] in Bunkr Sztuki in Cracow (August 2016), where the photography “merges” as something inseparable, with text, installation, publication, document. Photography as a tool to create history or to support power structures. Photography looking at itself.

Today, photography also likes to go back to its origins and to discover the artistic potential in the rarely presented today silver or bromine techniques, examples of which could be seen at the 10th Baltic Biennale of Contemporary Art in Szczecin, entitled “Morze. Od estetyki do ekonomii” [The Sea. From Aesthetics to Economy] (2015/2016).

Contemporary techniques in photography, both analogue and digital images, allow to register details without losing details in the lightest and darkest areas, with a large tonal range. Good and somehow thematically related examples can be the photographs by Sebastiao Salgado from the “Genesis” cycle presented in 2016 at Centrum Spotkania Kultur in Lublin, as well as the film directed by Ciro Guerra entitled “Embrace of the Serpent” from 2015.

In the black and white photographs of the famous Brazilian artist, apart from many corners of the world, showing the nature with the intentionally absent man or with a man living in a natural and primeval harmony with the nature, there are mainly blacks, representing shadows and absence of light, and whites understood as lights with a range of tones individually characterizing the blues of the sky, whites of fogs, greens of plants, and so on. Looking at a black and white photography of the Amazon rainforest is a lesson in colour for the brain and the imagination, a play with something unnameable. It turns out that we understand colours very precisely without the need to name them, or even to actually perceive them. Similarly saturated with colours are images in the black and white film of the Columbian director, telling a story of a spiritual journey of two men, a scientist and a shaman, through the Amazon forest. For the above mentioned artists, blacks and whites became the language of art, consciously chosen, used not only as a method of documentary-like stylization or of polishing mere reportage photos by giving them graphic features (granularity, texture).

Most of all, the use of colour reduction makes the photographic and film narration less real, thus directing the reflection towards the superior idea of beauty. It seems not so much the tool of creating and “spiritualizing” the reality, but a method of discovering something already existing in the world. As if the photographer and the film-maker were suddenly faced with inexpressible beauty, saw it in amazement, uncovered it and showed to others.

In works by Joanna Mieszko-Nita, blacks and whites surely create a colourful painter’s vision of the world, to some extent contributing to idealization and ennoblement of not the paintings themselves, but rather the concept of the painting landscape. However, one must admit that the black, as in graphics or drawings, cuts all forms out of the white, the darkness tears out from the light all that which we perceive. Here, white is not light, by the power of which the obviousness of things, the reality is created. In this reversed perspective, the Earth, people, the whole visible world would be something very imperfect, torn from the light, something not yet covered by darkness, a place in between, where all forms and life, movement, art are created, but without certainty that all this comes together in some homogenous perfectness.

This might be the most interesting moment of these paintings, when layers of black create structures on the verge of legibility, full of lurking darkness, just before it frees itself, like in the prison graphics by Piranesi, and turns into terror, but still frozen. When the eyes stroll on the blackened synthetic imperfections of rows of historic facades of Szczecin tenement houses, the reason stops at the threshold of the ethical shock over the layers of history of this place. The layers of black do not lose their rhythm, which can be felt in particular in the numerous repetitions of single strokes. This rhythm, however, does not cause movement, except for the circling whirlpool in the view of Gryfice. Here and there, a kind of industrial uncertainty can be experienced, an anxiety, like in the presentation of Lower Oder.

In the above mentioned examples of photographs by Salgado and the movie by Guerra, the landscape provides a form for both types of expression, it is a starting point for deliberations about the diversity of the visible world. In the paintings from the discussed cycle by Joanna Mieszko-Nita, familiar divisions layered horizontally, vertically, sometimes even, quite risky, diagonally, can be easily recognized as landscapes, thematically and compositionally defined in the art of painting, and then again in the photography. A landscape, in short, is a seemingly obvious, since easily imposed, method of organization of a plane (we paint what we see), opposite to an abstract painting with its open composition and the prohibition to present anything even slightly resembling something. Here, all elements are “directed” according to the rule of eliminating all internal tensions, balancing of powers, avoiding emotions. Movements of the brush, sometimes swiping and energetic, from the first to the last one, are controlled, traceable, equally thought through.

The same applies to the perspectival illusion, on principle always supported by landscape painting. The third dimension, resulting from the depth constructed by differentiated sizes and lengths of spots, disappears every time at the surface of the canvas. Brush strokes, like wefts in the warp, become equal and simultaneous. The artist, by making them visible and clear, creates an illusion of a patterned cloth. Landscape components, according to the artistic suggestion of Nikifor, are soundly analysed here and reasonably used in order to create yet another good story about the universe of the reality. Luckily, Nikifor’s spirit inspired the painter in creating these works.

![Joanna Mieszko-Nita - Born in 1969 in Trzcińsko-Zdrój. Graduated from Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Sztuk Plastycznych [State School of Fine Art.]s in Poznań. Diploma at the sculpting faculty headed by professor Józef Petruk in 1996. Her diploma work – a sculpture set in limestone entitled “Zmagania” [Struggles] – is displayed at Malta lake in Poznań.](https://galeriaart.pl/artists/img/mieszko-nita_profile.jpg)