Contemporary Baroque

The Baroque era and its art arouse rather contradictory feelings these days. The Baroque exaggeration, redundancy, and expression do not seem to fit our times.

Maybe a Baroque palace will still pass, but if it’s to be a church, then it should be a quiet, Romanesque one, to help us get away from the noise of our times. A Baroque church would be far too much and would probably distract rather than encourage prayer. Moreover, when we look at art, we choose Rembrandt rather than Rubens, Caravaggio rather than Carracci.

But on the other hand, there is such potential in Baroque still lifes and elaborate religious or mythological compositions. You just have to not be afraid. Recently, a new and intriguing person has appeared on the artistic horizon, who, as can be seen from the first glance, is not afraid of Baroque, exaggeration, or drawing on historical models and themes. In addition, she has great painterly ease and a sure hand, perhaps even a master’s hand.

Julia Medyńska has a rather complicated biography. She was born in Gdańsk, lived and studied in the United States, is now living in Poland, and will probably stay here for some time. This complexity also applies to her painterly manner, which openly and unceremoniously references the Baroque masters. I write “Baroque masters,” but I think that at times it would be very difficult to say which ones... Something comes to mind, something rings a bell, but if we were to point to a particular painting, a particular painterly address, we would have trouble pinpointing it.

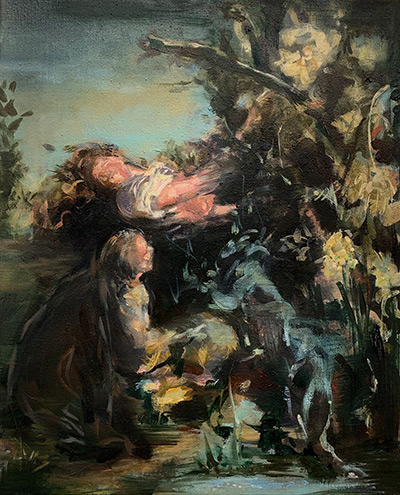

Yes, there is a scene with Narcissus. Narcissus often recurs in art because he is one of its mythical discoverers, creators. As Leon Battista Alberti wrote, “The inventor of painting was [...] Narcissus transformed into a flower; since painting is a flower among all the fine arts, the Narcissus story can be perfectly adapted to painting. What is the art of painting if not the capturing of that mirrored surface with art?” Julia Medyńska’s first version of Narcissus focuses on a floral motif. A young man among flowers, almost like a flower himself, but not at all a narcissist. Moved, with nebulous facial features, it is not actually clear whether he is beautiful or ugly. Unusually, he turns his gaze in our direction, and this is not a typical framing of him. Perhaps this is in keeping with what Zbigniew Herbert wrote about him: “Contrary to the legend which attributes great beauty to him, Narcissus was a common lad with vulgar features, impure complexion, broad shoulders and long limbs.”

The most famous one was painted by Caravaggio and can be seen today in Rome’s Palazzo Barberini. However, the one in the painting by Julia Medyńska does not reference this composition at all. He is calmer, more enigmatic, more delicate. The indistinct figure becomes even less clear on the moving surface of the water. Narcissus seems to pass into himself rather than look at himself. He is probably engrossing to himself. And if I had to point to what I could relate his composition to, I would rather look at one of Rembrandt’s most beautiful and intimate paintings, A Woman Bathing In a Stream (Hendrickje Stoffels?) stepping into the water, from the collection of London’s National Gallery. In both of these paintings there is a similar atmosphere and colour scheme, except that in Medyńska’s Narcissus, the whole is more enigmatic.

The most expressive of her paintings, The Minotaur, Dance by the Lake, Bathing the Boy, actually look as if they were some little-known oil sketches by Rubens or van Dyck. Bathing the Boy seems to reference the often depicted scene of Moses being fished out of the Nile. The three ingredients are right – a woman, a child, water – but there is no basket and of course no entourage accompanying Pharaoh’s daughter, who was said to have fished out the crying child. It is not important whether the association is accurate, what is important is the unobvious way in which this scene is presented, the peculiar carelessness of the execution, the great haste, the unwillingness to finish. Soft flowing paint matter, opening rather than closing shapes. This is also what Dance by the Lake is like, like some kind of bacchic scene – violent, exaggerated, powerful. The same is true of The Minotaur, where, although there is no blood, which should appear, the red of the dress and the drapery is so strong that even the red of blood pales in comparison. The violence is in the motion, it is in the incompleteness, it is in the colour.

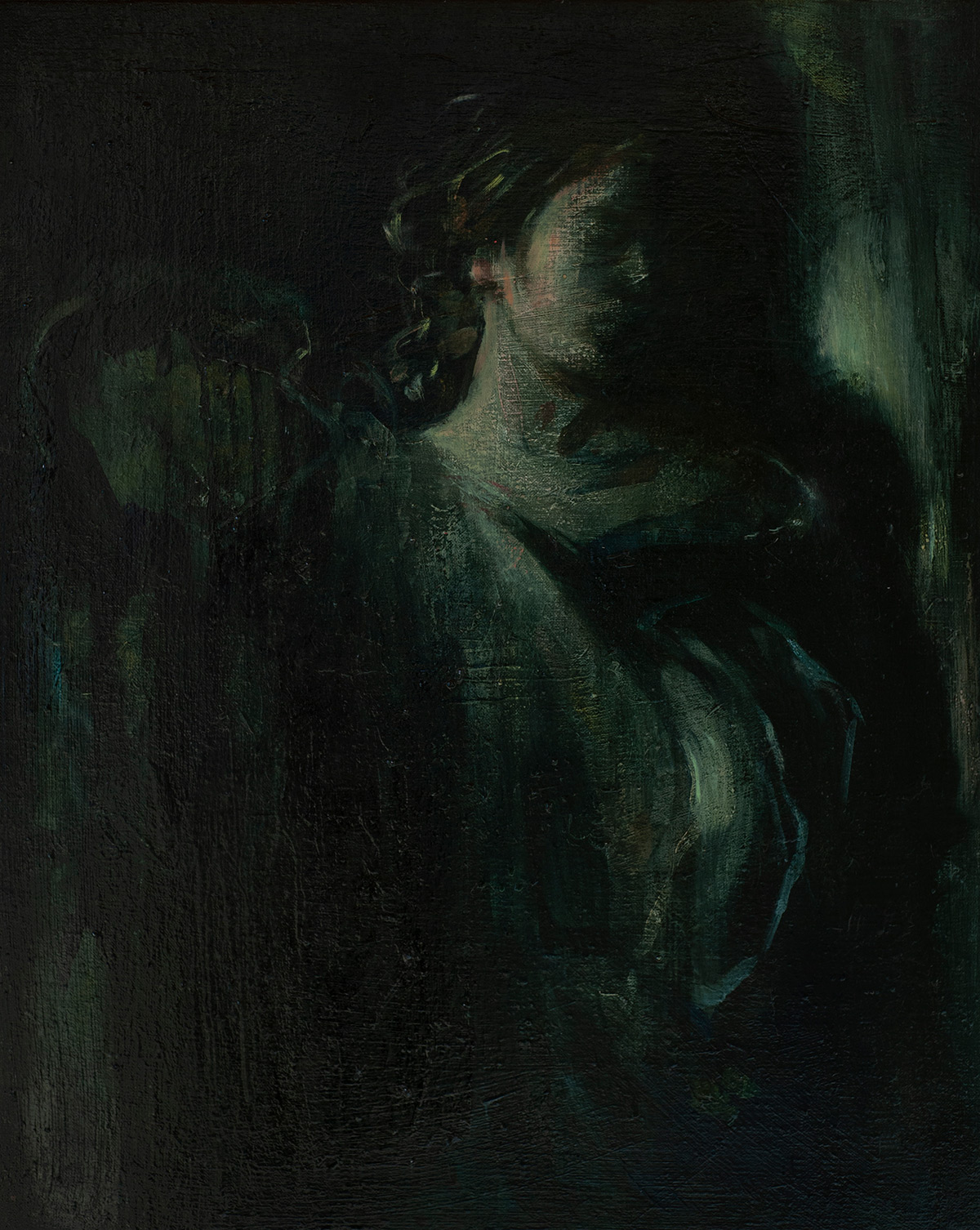

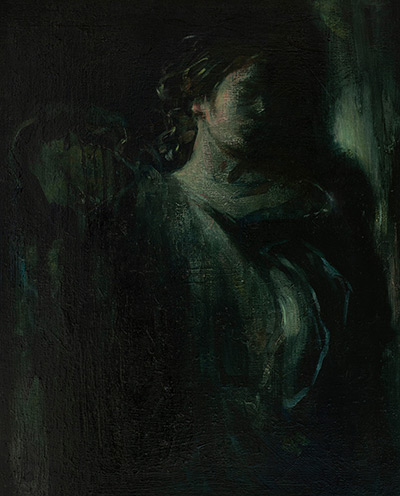

But there are paintings like elegies, paintings like the sweetest and most serene ariosos, delicate quiet and subdued, a mezzo voce, painted in a half-voice or perhaps even a whisper, monochromatic and so calm that their serenity is simply astonishing. Like those of Vermeer’s most economical paintings with single female figures, The Lacemaker or Girl with a Pearl Earring. Or, to recall the Italian Baroque masters of female beauty, Francesco Guarino, Guido Cagnaccio, and Francesco Furini – these figures could have come from their paintings, but they are completely devoid of any historical, mythological or religious attributes. The range becomes limited, subdued, the modelling more controlled, calmer, smoother. The faces, though general rather than particular, and certainly not of a portrait nature, persist in a kind of suspension, removed from times and eras. There is some reference to the past, but somehow proverbially undefined, as in the fairy-tale phrase: a long, long time ago. And these characters, although less spectacular, are perhaps more suited to our times, our sensitivity, and aesthetic tastes. Such are Medea, The Dressmaker, and The Beheading, with single figures or even just busts, calm, but with a drama or even tragedy written somewhere inside, the titles refer to these dramatic contexts. I will not tell the story of Medea, or of women holding the severed heads of men in their hands.

And finally, the still lifes. Sometimes, again, they seem to be transformative works of specific paintings, from specific painters; but there are also others, which are certainly independent works of the artist who decided to create her own compositions based on old patterns, but at the same time transforming these patterns. You can clearly feel the northern influence here, the Dutch and Flemish works were rather the inspiration. Although, again, Julia Medyńska has completely abandoned accuracy and literalness, but the character remains.

I am particularly drawn to the floral still life, which quite faithfully repeats the painterly patterns of the north, but at the same time is streaked with paint from above. A seemingly simple treatment, but this intervention is somehow very appealing. It is a disturbance of order and peace, a mixing of two orders, Baroque and modern. A seemingly simple treatment, which has been done many times before, so there is no point in mentioning its predecessors, but under Medyńska’s brush, it gains in strength and originality. The mixing of the orders is effective and disturbing. Perhaps the anxiety is heightened by the fact that a truly well-painted floral composition is attacked by paint flooding in from above. I thought of the paintings by an artist I have recently become very fond of, namely Abraham Mignon. He was, of course, a master of detail, and a great one at that, but in some strange way, something of the character of his painting has found its way into this painting as well.

Julia Medyńska has complete control over her painting matter, despite giving it infinite freedom and lightness. Perhaps the word irreverence, or even flippancy, could be applied here. This is what I feel when I look at these otherwise very diverse but always recognisable images of hers. I will gladly see more of them.