A colourful tessera

Painting does not have to tell stories or take pictures; its objectives are deeper and purer: it gives you an opportunity to express yourself personally.

Zofia Matuszczyk-Cygańska

Tessera

In the Ancient Rome, the Latin name tessera, probably of a Greek origin, was distinct with its rare multi-layered meaning. Initially, a cube used in the game of dice was so named. A dice or plate being a material for laying out a mosaic was also termed tessera; and it was with such elements that monumental images were composed in the ancient and mediaeval times. As a military custom, tessera was a square tablet designed for differentiating between an ally and the enemies. In everyday life, it was a sign exchanged as a proof of friendship; even the word tessera itself was used to described friendship, metaphorically. And it so happened at times that the leaving visitor would be given half the tablet, so that they could be received back as friends at showing it. The Italian language has preserved the name to denominate a museum or library admission card.[1]

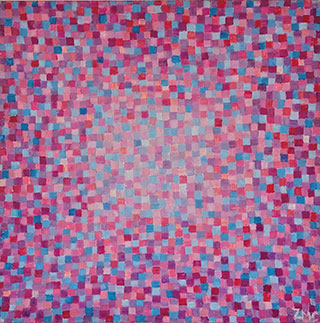

I have quoted the fragment above as it seemed to me to be right ideal for attempted description of Zofia Matuszczyk-Cygańska’s paintings, as those dices, squares, little crystals whirling in front of our eyes are but enlivened tesserae. I am fully aware that the word is not commonly known, but once it exists, and what’s more, can ideally described what goes on in Zofia Matuszczyk’s paintings, let’s retain it for the purpose of our attempted description here.

Point, comma, tessera – such was the painting order of scales of the basic element building the paintings of pointillists, impressionists, and, Zofia Matuszczyk-Cygańska. I have termed a ‘comma’ what is referred to as a divisionist technique in impressionist and post-impressionist paintings. Even if someone would associate what Ms. Matuszczyk does in her paintings with a pointillist method, I hasten to add that this would be quite an improper and erroneous association. Georges Seurat, the technique’s originator, died so young man that he hadn’t manage to write anything on it. The task was fulfilled by Paul Signac, a friend of Seurat’s and propagator of that painting idea, who wrote, inter alia:

This method, ensuring the achievement of sought-for results thanks to a purity of colour elements, their being appropriately dosed, perfectly mixed in the viewer’s eye, does not have to consist in a pointed texture, as they usually tend to figure it; one may apply beats of a paintbrush of any shape, as long as it is done clearly, without a wiping, using dimensions proportional to the picture’s size ... [2].

So, a certain freedom was admissible, but at the same time, one was not supposed to mix the colours – only pure colours should have appeared in a painting, which, when processed by the eye, were to change into colours other than basic.

Colourful inventions

-pasts through colours, or perhaps, through colourful arrays and putting them in tune, is the job that almost completely fills the old artist’s life these days. Colours on the palette change, as does the climate in the atelier. Yet, ‘atelier’ is too serious a word with which to describe the small room in which Zofia Matuszczyk-Cygańska paints her pictures, some of them being quite impressive in size. The very way her palette looks is virtually a piece of painting, designed. Most frequently, colours squeezed out for the first time would not really change much in the course of the artist’s work. New colours need being added rarely, they would rather infallibly emerge from those colours which have been there on the palette from the very first moment, the one in which the entire composition’s game was invented. When describing the paintings’ colours for herself, the painter would use out-of-date or simply forgotten terms, such as ‘lilac’ or ‘ginger’. Such words are not even used any more for describing clothes, but they appear extremely suited for the purpose here, and for the person using it. This is a peculiar acrobatics, and it seems most important to keep the balance between all the colours admitted to the canvas. Some of them are completely ephemeral, emerging from almost incidental mixings, whilst others result from the artists carefully searching for an infallible tone to resound, that is, disclose itself to our eyes in its purest form. Building those colourful compositions consists in compiling and enriching, to a maximum extent, the game emerging around one tone, in a manner, however, so that no impression of monotony is triggered but for a little while.

One definitely cannot speak here in terms of lacking colour-related invention. Variations on a theme, that; the theme being colour.

The basic colour which sets the area of artistic quest: red, rouge, blue, azure, green, yellow. Saturating the colours is in progress, as is enriching the canvas, cramming the consecutive colourful associations into it, enrichments, vibrations of the painter’s palette which seems unfinished – although today, we have Panton strips, don’t we, and even the most casual or astonishing colour arrangements have a number attached to them in the scale of visual capacities existent in the world of our sensual observations. It is actually quite affecting that painters still tend to cheat the optical mathematics of verifiability of the Panton range.

Form rejected

...the most important, most drastic and incurable dispute is the one that our two inner strivings have: the one desiring a form, shape, or definition, and the other one which defends itself against a shape and doesn’t want any form. The reality is not something one could completely enclose in a form. ... Form is not in accord with the essence of life. Yet, any thought that should be willing to determine this insufficiency of form, also becomes a form....[3]

In her abstract painting compositions, Zofia Matuszczyk-Cygańska has no doubt rejected a form. The form of a painting, or, forms in a painting, have been replaced by colours. It is their intuitive order that sets the painting’s form, and, what’s more, it becomes its only content, indelible order, the only hierarchy of values, a logical lecture on a graphic order exercised on the canvas’s surface. Its lasting for ever, the paintbrushes put aside, is wielded by an intuitive play of colours that is played in the course of a painting process producing a painted picture – charades of colours which have eventually created a given canvas. This is what has happened in essence, though no-one stated that precisely such an outcome should have emerged from that particular ‘colour game’, as Jan Cybis described it.

Submitting herself to the reign of Colour came at a very late date. This process took place in the recent years. making this decision enabled Zofia Matuszczyk-Cygańska to entirely focus on paintings created with colourful tesserae. One can feel a great swing taken to make those paintings, as coupled with technical proficiency and executive efficiency. Once all the dilemmas are over, the only issue becoming Painting, those paintings very soon gained excellence. The artist herself admits that it was only in the recent years that she could quietly go into painting. Her earlier years, devoted to gainful work and the family, was a much less artistically fertile period, deprived of that calm certainty which so powerfully springs out of her recent works.

Discovery

I can remember the astonishment as they appeared a few years at the Art Gallery. The first to come was one, or perhaps two, of the older paintings that triggered interest among our permanent customers, and artists as well. One of Matuszczyk’s works was bought by Edward Dwurnik, surprised and astonished at the canvas made by a painter he hadn’t known so far. Her appearance in our Gallery was a revelation – such a discovery is not commonplace at all. Ms. Matuszczyk had made a name for herself, indeed, but this was limited only to the milieu of artistic cloth, tapestries, as the excellent jacquards designed for Ład Co-operative have been forgotten by many. A resemblance could be found at the big display of the co-operative’s output held 1996 at the Warsaw Fine Arts Academy Museum. One could find reproductions of several cloths and specific productions out of the artist’s enormous output. Ms. Matuszczyk was one of the key personages in the post-war history of Ład. She was one of the artists who introduced modernity, of an abstract descent, in the designs she made for this kind of fabrics. One her jacquard, dating to 1960 and called ‘Textural’, was simply an abstract composition with iridescent backgrounds against which irregular polyhedrons were piled up. At that point, the artist was already not far away from the definiteness of a tessera[4].

However, a really peculiar revelation was the finding of those paintings, made years and years ago, and virtually not known to anyone, but an even more interesting and fascinating thing was to watch the great painting talent getting reborn, that an unusually powerful gift which was manifesting itself in dozens of new compositions.

One has to admit that Ms. Matuszczyk’s curriculum vitae is not usual for an artist. The studies, started in 1930s, were interrupted by the war. In the Nazi occupation years, Mieczysław Kotarbiński, her beloved teacher, was killed. His Academy studio has produced also other outstanding painters, such as Halina Centkiewicz-Michalska, Jerzy Mierzejewski. She was to eventually graduate from the Warsaw Fine Arts Academy under Felicjan Szczęsny-Kowarski. Two of her paintings dated 1949 have survived, both being views of a port. Their bright and vivid colouring is indicative of their author’s clear relations not really with Kowarski’s studio but rather, simply with colouristic painting, so typical at the time to the Warsaw Academy milieu, then dominated by a group of those who continued the colourist tradition of the period between the two world wars.

Her subsequent paintings testified to a presence of modernity. In those canvases, the bright shining and pure colour is fading to the benefit of strong black contours, the colours becoming more toned-down, brown and grey shades replacing rouge or green ones. There are several such still-life and abstract pictures. Out of those compositions, whose nature is clearly searching, still different works were to emerge: abstract compositions – very interesting ones, to my mind.

Their form was startling as it was "irregular", with irregular divisions; an analogy with the tapestry art would be best useful for describing them. Those paintings were ones painted by a weaver, and the form, or rather, texture of tapestry onto flat canvas produced a surprising, but basically very interesting, result. Unfortunately, not many of those tapestry-like abstract works have survived, but perhaps, not so many of them have ever existed.

The next style to come was, mainly, geometric-like abstract works, in a spirit of tamed modernity of the latter half of the fifties and of the sixties’ decade. It is right to admit here that the seventies was not a good time for painting, in Zofia Matuszczyk-Cygańska’s artistic CV, as at that time she was mostly busy with her tapestries. So, she was weaving then. The decades of the eighties and nineties proved to be much more interesting, as they were richer in paintings. And it was at that time that the aged artist’s individual, and most interesting, idea was born as to her own painting art.

The glamour of mosaics

Zofia Matuszczyk-Cygańska was a travelling artist. The time of what was the ‘People’s Republic of Poland’ was not much benefiting a traveller’s job, but certainly, artists were a somewhat privileged group and they found it easier at that time to get out from here into the rest of the world. Ms. Matuszczyk was so successful that she even managed to visit Sicily. The complex of mosaics adorning the interiors of the Capella Palatina at Palermo, or the Montreale cathedral, are very impressive to regular visitors, not to say a word about artists. Although those interiors are dark, their golden backgrounds make them gleam and glisten:

The mosaic plate’s glass itself is supposed not to let the light through but to reflect and refract it. Its glare, like the glow of gold, is non-transparent.[5]

Something from that glace and the broken-down order of small dices must have remained under the painter’s eyelids, as they reappeared in the very interesting ‘transitory’ painting dating to mid-1960s, titled Prosty [‘Straight’]. That was a single composition, like an antic. No continuation followed. And it was only in 1990s that a painting titled Wesoły [‘Joyous’] was painted, where mosaic dices reappeared after a long pause: the painter has imposed a network of irregular tesserae upon a free geometric structure. A mixture of three orders has produced a new graphic structure which simultaneously revealed very clearly its entire temporariness, as best testified to by the later uniform tessera-based compositions.

In them, any content has already been done without irreversibly, and irretrievably. Thematic pretext such as Młyn [‘The Mill’], Butelka [‘Bottle’], Dolina księżyca [‘The Valley of the Moon’], Motyl [‘Butterfly’], have entirely vaporised, whereas those larger squares building them have changed into a colourful game made of pieces of tessera, or, a mosaic, if you like. Mosaic, after all, is similar to tapestry or fresco in that it is a type of monumental painting, and Zofia Matuszczyk-Cygańska is most willing to be a painter, the thing she already wanted at her early young age.

Beyond history

An art that, as we have described it, approaches itself, is characterised with a free attitude toward the tradition, without of any inferiority complex, and sometimes even authoritarian; it absorbs into itself whatever it draws upon. It uses that arbitrarily as a material, not fearing its not infrequently difficult diversity: stylistic, temporal, or territorial distances being borne by its ‘non-historicism’[6].

By now, as it seems, the painting art of Zofia Matuszczyk-Cygańska has achieved that entirely ‘non-historical’ point in its development. It has irreversibly become self-contained and independent, artistically and technically alike. Paradoxically enough, it has slipped away from a linear temporal sequence in the development of the art of painting. Her paintings might perhaps be closer to the times of Frantisek Kupka, Robert Delaunay, Piet Mondrian; as if a new, yet-unknown sheet has been inserted into the history of modernistic painting.

Thus, painting has finally won in Zofia Matuszczyk-Cygańska’s life and in her art.

Notes and references

- [1] Tessera sztuka jako przedmiot badań [Tessera art as the subject of research’], Cracow 1981, p. 5.

- [2] Artyści o sztuce. Od van Gogha do Picassa. [‘Artists on Art. From Van Gogh to Picasso’], selected and edited by Elżbieta Grabska and Hanna Morawska, Warsaw 1969, p. 62.

- [3] W. Gombrowicz, Dziennik [‘The Journal’] (1953-1956). Paris 1971, p. 122.

- [4] Anna Frąckiewicz, ed., Spółdzielnia artystów Ład 1926-1996 [‘Ład Artists Co-operative 1926-1996’], vol. 1, Warsaw 1998, p. 208.

- [5] S. Awierincew, Złoto w systemie symboli kultury wczesnobizantyjskiej. w Na skrzyżowaniu tradycji (szkice o literaturze i kulturze wczesnobizantyjskiej) [‘Gold in the early-Byzantine cultural system. At the crossroads of traditions (essays on early-Byzantine literature and culture)’], Warsaw 1988, p. 188.

- [6] W. Juszczak, W stronę asymbolizmu [‘Toward anti-symbolism’], in: Tessera, op. cit., p. 102.