A painter from the foothills of the Jasna Góra Monastery

Let me take you for a walk around Częstochowa. My itinerary includes a stroll down the streets of 7 Kamienic, Św. Barbary and Wieluńska. We are in the vicinity of the Jasna Góra Monastery, in the very heart of the pilgrimage centre. The outline of the monastery, with its soaring steeple, towers over the surrounding area, the parks and the little alleys full of shops and stalls with devotional articles. Rosaries, crosses, medallions, holy pictures, incenses, little stoups… Among these souvenirs one may also find figures – Mary Immaculate, Our Lady of the Rosary, the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Saint Francis. Most of these figures are of little artistic value as they are mass-produced. Such souvenirs have always been very much in demand in this area, so production in the Jasna Góra neighbourhood is thriving.

In the past the artists of Częstochowa made numerous attempts to raise the artistic value of devotional articles. In 1998 the famous local sculptor, Natalia Andriolli, established a studio of church sculpture and artistic industry. And since 1902 W. Salamon manufactured interesting (with respect to form and decorations) porcelain figurines of various saints as “a counterweight to the usually tacky gypsum figurines”[1]. In the interwar period in Częstochowa there were several manufacturers producing sculptures and ceramic and gypsum figures. ‘In 1945 a small group of artists led by the renowned ceramic artist Wanda Szrajberówna, Sister Aniela Józefowicz, and a graphic artist that graduated the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, Irena Lechowicz […] decided to start manufacturing devotional articles in order to raise their artistic value. They managed to retrieve a closed factory of porcelain and gypsum figures[2].’ As a result, in late 1945, the Czyn earthenware factory commenced operations. The factory used both traditional patterns and new models designed by artists.

It’s also worth quoting Janina Orynżyna’s interesting account of her visit to Częstochowa: ‘In 1944 I found myself in Częstochowa and I had an opportunity to visit their numerous stores with devotional articles […]. The oldest and the best-stocked ones were the shops of Jędrzejczykowa […] and Bielecki […], both belonging to the new rich ‘god-makers’, as Czestochowa painters used to be called. In the store of Jędrzejczykowa I found a really rich material that gave me a wide review of production in that field. Obviously, the majority there were gypsum Madonnas of various sizes – from 10 cm to 2 metres in height – oil-painted white and in blue robes, with sweet faces and of conventional beauty. By the serpent, rosary or the arrangement of hands, the experts could differentiate between Our Lady of Lourdes, Mary the Gracious, Our Lady of the Rosary, etc. Amateur figure-making artists would put stones inside the figures in order to make them look more solid[3].”

In Jacek Łydżba’s atelier I saw over a dozen figures following the rules of the long-lasting convention. For some time now the artists has been decorating ‘holy’ figurines. He copies well-known iconographic models – the Sacred Heart of Mary, the Madonna and Child, the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus, Saint Anthony of Padua, Mary Immaculate, Our Lady of the Rosary. Jacek makes his figurines very carefully and with a real artistic touch. He chooses gypsum models instead of resinous ones and works with a really breakable material, which is far more demanding. He acutely and thoughtfully covers the forms with colourful enamel, using pure hues exclusively. The holy figures seem to be bathed in intense blues, reds and yellows. Robes, gowns and habits are decorated with miscellaneous patterns and ornamental elements. There are dots, smaller and bigger, and sometimes irregular motifs of hearts, flowers or flames that are scattered on the garments. And all this is fantastically harmonised. I noticed some unconventional nuances and details, e.g. a red heart on the chest of a light blue ‘God-bless-you angel’ and his blue hair. A cheerful Saint Anthony of Padua wearing some strange multicoloured headgear also drew my attention. In another version the habit of the same saint was decorated with branches of white lilies and with wild flowers blossoming at his feet. One of the figures had the words of a prayer written on its back. I felt touched by the representation of the Mother of God with a bleeding heart – a coloured stain disturbingly runs down, dyeing Mary’s dress red. Jacek creates a new quality as his saints are fully independent, creative productions. For the artist, a white gypsum trunk – that unnatural form – is merely a starting point for further artistic activities. A three-dimensional model is like a new blank canvas on the easel.

In 2010 in the Permagon Museum in Berlin an exhibition called Colourful Gods. The Colours of Ancient Sculpture was held. A dozen or so reconstructions of polychromes on Greek figures and bas-reliefs were shown. What were the audiences’ reactions? Surprise, stupefaction. ‘The polychromes put on the gypsum copies of the original figures strike with strong colours. The hues often contrast one another – the intense light blue of the lazurite next to ochre, malachite green shines against cinnabar. And all this according to the Greek term of mimesis, so the sculptures are painted to perfectly imitate reality[4].’

Sculptures and architectural components have been painted since the earliest times. Traces of red ochre were discovered on the Palaeolithic figurines of Venus, decorative bas-reliefs on the walls of Egyptian tombs and figures of pharaohs, archaic Kore statues and the sculptures of Greek gods. Even the houses of ancient Rome were colourfully decorated. The Middle Ages was also an era of bright colours and shine. In philosophical writings of that time the issue of hue, shine and darkness is of great significance. ‘Look at the world and everything that there is and you will find a great number of beautiful and attractive things... Gold and jewels have their own glitter, the grace of a body is of its own perfection, and paintings and garments have their own hues,’ wrote Hugh of Saint Victor. The interiors of Byzantine churches, covered in mosaics glittering with pure gold, gave visitors an almost sensual ecstasy. In Poland polychromes could be found, for example, in the church in Strzelno, while the façade of the castle church in Malbork was decorated, until 1945, with an exceptional, gigantic fourteenth-century statue of the Mother of God that was firstly covered by polychrome and then mosaic. Resembling a jewel, the statue was a distinctive decorative element of the façade of the Upper Castle. The figure of the Mother of God was wrapped in a golden robe with a red overcoat thrown on top of it. The coat was richly patterned, had a blue lining and was ‘laced’ with golden birds. A white shawl was wrapped around Her head and the Baby Jesus had a red dress decorated with golden flowers.

The bold colours and original decorative elements in the figures of Jacek Łydżba please the eye. This kind of expression is deeply rooted in the tradition of art – ancient, pagan, but also Christian and West European. The passage of time, wars, disasters, but also purposeful actions of people and mistakes of heritage conservationists have resulted in irreversible damage and the destruction of numerous historical objects, buildings, decorations, polychromes and mosaics. Nowadays it is widely believed that the works of ancient architecture and sculpture were severe and austere. We do admire their structure, shape and the beauty of the material, but we never remember about their painting virtues. The interiors of medieval churches were colourful, and white Greek marble sculptures were painted. Colour beautifies, strengthens the power of expression and has a symbolic meaning. In religious works the symbolic layer has always referred to God. Azure blue has always meant the heaves, the air, and was the sign of God’s wisdom. It’s a ‘spiritual’, contemplative hue contrasted by ‘earthly’ redness that symbolises vital powers, fire, blood, but also power. Green is the restoration of life, white – purity and innocence. Black was associated with unbelief and sin. Jacek uses hues in an intuitive manner, but he never rejects the canonical rules and the symbolism, while this unimpeded colourfulness allows him to hide the conventionality of the forms.

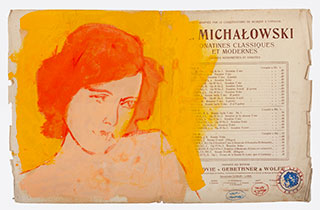

The religious motifs have been present in the art of Jacek Łydżba for years now. I am thinking of his paintings with the delicate, very sensual representations of angelic figures and with battling and, thus, more menacing archangels. The artist also continues the series of paper paintings where the motifs are projected by means of a template. These works are characterised by restraint and frugality. We can only see single outlines (an angel playing an instrument, the face of the Mother of God, the serpent – the symbol of sin, the Sacred Heart of Jesus) that are free of redundant details, and boldly used colourful patches with typical ‘smudges’ in the background. The figures of the saint are more naïve, but even in this imposed form and convention the artist manages to find place for some individualism and artistic gesture.

Notes and references

- [1] A. Jaśkiewicz, R. Rok, Z dawna Polski Tyś Królową. Pamiątka z pielgrzymki do Jasnej Góry, Muzeum Częstochowskie, Częstochowa 2002, p. 22.

- [2] J. Orynżyna, Dewocjonalia częstochowskie, „Polska Sztuka Ludowa”, Issue 30, 1976, No 2, p. 119.

- [3] Ibidem, p. 115.

- [4] P. Kieżun, Czerwone usta kore, „Kultura Liberalna”, 2010, No 84, reprint [in:] https://kulturaliberalna.pl/2010/08/17/kiezun-czerwone-usta-kore/