The World Is A Human Being

Show me what you have in your pockets, and I’ll tell you who you are: a simplifying psychologism, that. All the less can it apply to an artist, since it does not suffice for one to watch a work, if one seeks for the truth about its author. Certainly, an art historian would find it fairly easy to see in Mikołaj Kasprzyk’s paintings analogies to the Gothic- or Renaissance-era or surrealist art, then already getting to know the painter’s aesthetic inclinations and predilections. Yet, an artist does not reflect him- or herself in their paintings as in a mirror. Mikołaj is offended by exhibitionism in art; as he himself says, he is personally much more emotional a person than one could probably guess judging from his works. So, a picture is a picture.... But now, we are talking paintings, chiefly....

The character in your works is (a) human being. For you, is it a stand-alone theme?

Yes, because humans are very interesting. First of all, in a formal sense: as a model, an object. After all, man is what I’m after as far as art is concerned, in the first place. Architecture, landscape can trigger my delight, but it is humans that prove most attractive to me. Besides, humans are interesting, since the world itself is interesting, whereas man is a recipient medium for the world, one who takes part in this world’s vicissitudes. In fact, the fate of the world and that of humans are identical, and in this sense, the world is humans. When I wish to make a reference to the reality, I’ll do it through a human being, for this is an entity being closest to me. I obviously do it intuitively, as I don’t formulate any philosophical-ideological convictions for myself, to be used in my work. I am immersed in life, and my painting simply displays reflections of this.

I do not read your paintings as some specific stories told. Unless they all could be viewed as a story on man, without a beginning or an end. To me, their charm consists primarily in a peculiar climate: there is no time, the moment you experience is abstract by nature. The objects shown are allegedly concrete: a figure with a watering can here, a guy with a weight there; and the result is...? More timeless, as if.

If this is so, then I’m pretty satisfied, as it means, I’ve done it. I do not verbalise it for myself, but this seems to be my program of sorts. A climate, a metaphor are indispensable to me; these are a method to attain sincerity. If I were to speak my mind frankly, I wouldn’t say a word at all. But this is not in each case intended as such; often, the effect is achieved rather semi-consciously.

The emotional layer of your works is subtle, ‘subcutaneous’, not ostentatious at all....

For sure, those paintings are not a direct reflection of my emotionality. In my paintings, I use this particular kind of writing, because I find any ostentation merely disgusting. Sweating one’s blood in a piece of canvas? This is not part of my world.

Do you have a set of motifs which might be called a ‘canon’? A lonely human; a castle; or, a tree? You resume those frequently, or put them together.

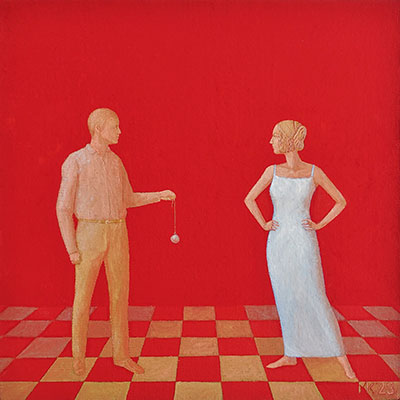

Indeed, the arsenal of my motifs is rather limited, but they do the job for me. A single figure or a pair of humans; a man and a woman – for me, this is the simplest way to communicate the various human relations, show a relation to myself. It also happens that I embark on identical, or very similar, topic, in order to find an even better, or different, solution to it. And at times, it ends up in success.

Is painting a profession for you?

For the recent dozen-or-so years, I’ve been working a lot, and very systematically so. I go to my studio, like a clerk goes to his or her office, even at an earlier time than they do, Sundays included. The technique I apply is simple: a solid drawing; classical perspective; a balance – this is probably somehow affiliated with my liking of early art. I have my personal rhythm of making my paintings, step by step: first, I take pictures, and then, based on those, prepare a drawing. Subsequently, I transfer the drawing onto my canvas, etc. My experience tells me what portion of work I can do a day, which reminds me a little of a ‘daily wage’ for someone making a fresco. And I’m amused by this kind of thinking about my own work.

In your paintings, as well as in what you’re saying, your fascination of the Mediaeval and Renaissance art is a reappearing motif.

Painting albums, from the Middle Ages to the Baroque era, is something I watch with delight, and then, ‘dark ages’ follow, as I see it, and it is only at the turn of the 20th century that I can find some enclaves of interest to me. And this is where the echoes of early art in my paintings are rooted; a kind of ‘let’s play an early artist’, that. But this might sound a bit suspicious, as one could say: “What echoing you’re referring to? Early art is an art in its own right, and what you do is painting some little men, so what is it there to boast yourself about?” So, I made up a tricky story on that. I once read about Oriental religions, and what I’ve been left with is some surface information, such as: Tantrism has much to do with eroticism and sex, and it manifests itself in this way. However, eroticism is reserved for the most well-off people; others must replace it with some equivalents, such as smelling a flower. Now, in the context of myself and the art of old ages, the thing is that that art is an eroticism and I am a modest flower smelling. Someone once said, what I do is post-modernistic. For my own use, I have coined a saying that a postmodernism appears wherever one can do just anything. So, one’s consent to someone else’s being not modern may be part of it. And this is something I’m at home with, as I don’t want to feel the pressure of being modern.

Is an idea about your new painting developing for a long time inside you? Is it that you have thought every detail over, from the start until the end, or rather, is it an impulse that matters most?

I don’t ever have creative impulses. I would go mad if I had to work ecstatically every day. I have to be quiet while I paint. People often tend to ask you about your inspiration; but what happens is that sometimes I’m doing better and sometimes, worse. Painting is a difficult thing, and the matter I deal with is much resistant to me personally. But the effort you put into it makes you satisfied as well.

You have elaborated your own painting language; you have a peculiar handwriting, consisting, as you’ve said, of what you’re capable and incapable of. Is your appetite greater than that, though?

Oh yes it is, but I’m not making any breakthrough changes. My evolution is very slow and discreet, and I cannot see it in my everyday dealings. I set forth problems, or little problems, for myself, and then try to solve them.

So, what has changed?

To say it in brief: I’ve got brighter; my pictures are now even more conventional and less realistic; they constitute a sort of abstract boards. As to the technique, I use only a few colours, and have even quit some of them recently.

Is painting a subtraction, then?

This is what I feel at present, indeed.