Vertigo

Bogusław Deptuła talks to Katarzyna Karpowicz

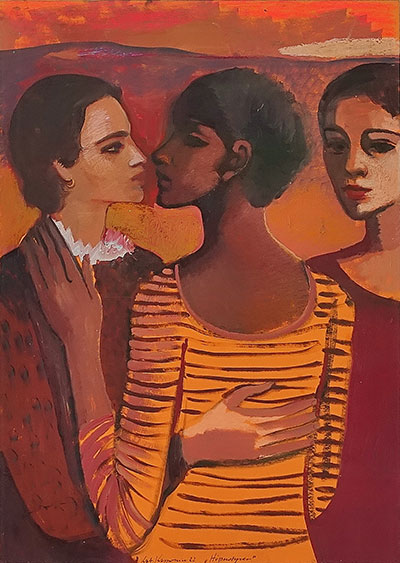

Your paintings are bittersweet.

I think there is a lot of sweetness and a lot of its opposite in my paintings, because that is also life, and I paint life. Sweetness and bitterness emphasise each other.

I feel a kind of melancholic veil that obscures all your characters and situations.

For me, melancholy is one of the most interesting things in art, in poetry, in music, in literature, in film. I am glad that you see it in my paintings. I don’t want the melancholy to dominate them, but it should be palpable. Anyway, I draw inspiration from film stills, which create such a melancholic mood.

Film stills? What films do you have in mind?

I was shaped by Fellini, Antonioni, Kurosawa, Buñuel, Bergman, Tarkovsky, and Kubrick. And then there’s David Lynch, whose Twin Peaks puts me in a particular mood. This atmosphere then permeates my paintings. I’m fascinated by the images/stills.

I thought the fascinations were more from paintings than films.

Films do not translate directly into painting. What matters is the mood, my inner world, reflected in the painting. I tell the viewer about myself. I carry memories from long ago, from my childhood, from my teenage years, when I literally absorbed all those works of literature and film that shaped me so much. It is probably also thanks to this that I express simple things and emotions in my paintings, such as love, sadness, passing, longing, loneliness, or closeness to another human being. I tell the story in a theatrical, somewhat cinematic way.

What came first – painted pictures or moving pictures?

First there was my constant drawing and painting and telling the same story over and over again.

And I suppose the house you grew up in?

The family home, and the table where I sat in the evenings over a spread-out drawing block, with crayons. I drew while listening quietly to the radio, which did not disturb my parents. It was in the early 90s, they had Radio Two on; I loved the radio plays, the novels being read. And actually nothing has changed for me to this day. I keep coming back to the theme of streets, children, and swimming pools. And if you put these images in the order in which they were created, you could make an animated film. So first there was the picture, but this picture is constantly moving in my imagination.

You titled this exhibition Maurin. What does this mean?

They are an imaginary character from my childhood. My mother wanted to call me Maura. The original idea lost out to reason, and I became an ordinary Katarzyna. Maura, however, stuck in my mind as an alternative figure of myself. Since childhood, I have wondered what would happen if I were a completely different person. And what would it be like to live the life of someone else, in another part of the world. And through my drawings, I moved into these worlds and created a different personality for myself. In these characters, I conjured myself and created new possibilities for myself.

I played a game with my sister which involved us imagining what was happening somewhere in the world at the moment. We would stroll through the Wolski Forest and say, “at this very moment there is someone in the world clapping their hands, because they have just listened to a great concert”. And it turns out that I constantly do the same thing in painting – I walk up to a blank canvas and imagine what is happening in this alternative world at that moment. And the viewer who stands in front of this painting can take on the role of one of the characters and imagine this world, find themselves in its mood.

The character of Maurin suits me both as a boy, and as a girl, the gender does not matter. It might as well be a dog or some other animal. The title of the exhibition is very personal, but it is by no means a self-portrait. It is an attempt to encourage the viewer to live another life, to choose one of these characters and live it.

I feel that Maurin is such an ‘everyman’, they are you, but also everyone. Interesting that there is no defined gender here, these figures are somewhat androgynous. Their sexual characteristics are not highlighted, accentuated, perhaps not overlooked, but not emphasised. You added animals here, and rightly so, after all, there are times when we think of ourselves as some kind of animal, that we would like to turn into one.

Into a fat cat at a granny’s house in Spain, who has a big balcony, a big garden, and a good life.

And a big bowl.

And a view of the sea, with no worries.

So, Maurin, the everyman, is a figure of someone who will be put in different situations.

There is another interesting story in the background, because it turned out that there was someone called Krzysztof Maurin. Professor of mathematics, physics and philosophy at the University of Warsaw; reportedly an extraordinary scientist, he led a seminar on how mathematics relates to art and philosophy.

I believe he was the brother of Jolanta Maurin-Białostocka, the wife of the most eminent Polish art historian, Prof. John Białostocki. She was an art historian and a writer, and she translated from German.

In is theory of mathematics, he crossed over into metaphysics, which is very close to my heart.

You mentioned a swimming pool. What is a swimming pool?

When I swim, I lose the burden of everyday life. In these pools, which I return to regularly, I talk about freeing ourselves from our own human limitations, which sometimes tire us and overwhelm us so much. In the pool, with every bounce, to the rhythm of your breathing, when you relax, you are transported for a moment into blissful oblivion. And that is a respite, a rest.

You fall out of time.

That’s right. Note, however, that there is no water in these pools, they are very abstractly conceived pools. Although I am a figurative painter and many people think that I paint realistically, in these paintings, I think in a very abstract way.

What is a mask?

The mask for me is an extension of a person’s story, their emotions, their life struggles. The mask builds mystery. By covering my face, which is really my soul, I expose it even more, until it becomes naked, honest, and very vulnerable.

And what is a mirror?

I can’t define a mirror yet, as I have only recently started painting this motif. It first appeared in a scene where a boy who looks like Franz Kafka holds an oval mirror showing a woman’s lips painted in red lipstick. I sensed that the mirror was simply a memory, a recollection. A symbolic way of capturing something we no longer have or something we miss.

What is a circus? What kind of place is it?

It is a bad place. I have radically changed my mind about the circus. For me it is no longer that place of childhood fascination when the circus came to Szczebrzeszyn. In this fascination, delight was mixed with fear, because for a child, the circus is just such an experience of delight laced with fear.

Just like with fairy tales, children like them and are a little scared of them.

Later I entered Picasso’s circus world. I don’t remember any bears showing up there. Anyway, I have been against animals being in the circus for many years.

There is no bear in Picasso’s circus, no clowns either.

His circus stayed with me for a long time and made me revisit my childhood circus memories.

Are you aware that we are our own mortal symbols? We wear our own corpse skull under our living skin.

Yes, I have seen and felt this since I was a child. And it’s... I won’t say “obsession”, because that would sound negative, but it’s not a fascination either; it’s a problem I’m struggling with, and because I’ve always explained things to myself through drawing and painting, I keep coming back to this theme, the theme of transience appears in my paintings. Perhaps not in all of them, but in many. The skull, incidentally, is also a symbol of the mask. I am aware of my own mortality. I am not afraid of it. It is beautiful. And a little bittersweet, just like life, like what we started this conversation with: we are, we won’t be.

You are still a young person, but you have already had several such violent, personal, and health episodes in your life. Does it permeate into your painting?

These experiences enrich both me and my painting. In the paintings, my personal experiences become a universal story.

And what are these skies that are suddenly swirling in your images? Where did they come from?

A year ago, I had vertigo and lost my sense of balance. The world whirled, spinning even in my sleep. I had dreams where I was losing everything, getting lost in the city, having a constant sense of imbalance. Nothing pleasant, but my painting gained something: I began to see colours more intensely, because my brain rescued itself with a compilation of senses, suggested help in the form of a different perception of reality. And it was then, when I was still dizzy, and rehabilitating myself by standing in front of an easel, that I began to paint these vertigo paintings, in which you see a figure through a narrow created by two cramped buildings, with people standing in it.

The colours sharpened; I became obsessed with composition and detail. That’s when these skies were created – I tried to encapsulate my impressions as I walked down the street. Because actually, if your sense of balance is thrown off, it feels like you’re looking through a camera, as if Lars von Trier were filming your life. It’s just that the brain plays tricks on you.

You are in the privileged position of making a living from what you enjoy doing.

I used to say I was lucky, but now I give myself another way of looking at it, and I just say it’s years of hard work and luck.

Finally, I would ask if you agree with Milan Kundera’s phrase that life is elsewhere?

I was actually thinking about this recently, and I was worried that life really is elsewhere, and that I’m living that life in parallel elsewhere. I began to wonder if these paintings were not just an escape. I have always escaped into my own world, ever since I was a child. And that’s why I work so much, and paint so much, because my life is also elsewhere. I don’t know if I understand it in the way Kundera did. On the other hand, I actually move from the real world to a parallel, painterly world. Especially now, when I’m working so intensely, I have the feeling that I’m more interested in the life I create than in the reality that sometimes frightens me and from which I want to escape for a moment.

There is no point in deciding which of these lives is more real. But looking at these paintings of yours, I was thinking that on the one hand, these characters are so specific, and on the other hand, they are universal. That these situations are as likely as they are contrived.

And again, we return to my childhood game of probability of events, of fantasising about another life. And that’s beautiful.

Have you grown up yet?

I will never grow up.