I can collect my thoughts under water

Bogusław Deptuła: How is it possible that, when it comes to drawing, you have reached great mastery and worked out your own style, but you still cannot decide what your painting should look like?

Katarzyna Karpowicz: Maybe because I have done a lot of drawing since early childhood. Ever since I remember, I have done quick sketching. Whether the sketches were pretty or not wasn’t really important. What really mattered was to get the movement and the atmosphere across. Anyway, painting requires a different course of work. Drawing is easier to organise – it’s more difficult to go to a summer camp with a set of oil paints and everything else you need to paint with. Whenever I went to a camp, I would take a pencil, crayons and a small sketchbook. I used to sketch all the time – other children in my family at play, or my dad, or my teachers, my schoolmates in the classroom. It was a constant recording of moments, the surroundings, but also telling things that ran through my head. Because I would first draw out of my imagination and then from real life. In my secondary school, whenever I bunked off and went to the ZOO, I used to take my sketchbook with me. I didn’t realise then that by drawing non-stop I was practising, learning and that it would help me draw better and better. I never cared about it, since I did it for the need of drawing, out of my fascination with animals, people, and – above all – children, children in motion. I painted as well. In painting I was mostly into colour, while drawing was interesting because of a line. But I never looked for my personal style in drawing or painting. I do not really have to go into one specified direction. I just tell a story and that’s what makes me happy. I try to be honest and follow whatever is vital for me. And apart from the atmosphere, the emotions that painting evokes are vital for me. I stand in front of a painting by, let’s say, Beckmann and I am almost reduced to tears by envy and I ask myself: ‘how did he manage to paint it?’

I believe that painting isn’t about developing your own style, but simply about painting and searching. It’s also about going to a museum and noticing what has to be noticed in the paintings by Velázquez, Dubuffet or even in abstract art, e.g. by Kandinsky. Maybe a painter needs some time to grow up, work longer to find themselves, although later it all transforms… Peace of mind comes with time.

BD: It’s quite obvious that your style of drawing has been inspired by David Hockney. What painter is equally important to you?

KK: There are many. If we greatly admire a single painter, one day he or she may simply get boring for us or become too ordinary. I can say that recently I have been greatly impressed by expressionism and Kirchner. I saw his retrospective exhibition in Frankfurt and I felt deeply moved by the way he painted – with so much ease and courage.

BD: That’s recent, but I am asking about your older fascinations, the more permanent ones.

KK: Hockney is important for me not only because of the way he draws, but also because of his attitude to the motif of a swimming pool. These pools of Hockney and his figure itself – that speaks of his paintings in a way – really appeal to me. Naturally, there is also Balthus, which you can tell just by looking at my paintings. In my secondary school I even made transpositions of his paintings. I often use pieces of other painters’ works – Piero della Francesca, Giotto, Velázquez, El Greco. I am constantly discovering something new, so I think I could list the painters endlessly. Recently I have had a lot of admiration for Paula Modersohn-Becker, for example. I like looking at albums, but until I have seen a painting in real life, I cannot really say that I definitely like a particular painter. And if I want to boost my energy, a visit to a good museum gives me the power to ‘grab’ a canvas and paint something just for the sake of painting.

BD: And what about themes, where do they come from?

KK: The themes that are personal – swimming pools and now also rivers, or sleeping people with animals – are somewhere deep inside me. They partially stem from my dreams and partially from my memories.

BD: And why swimming pools?

KK: It all began in my childhood. Being 5 years old, I had some spine problems and I was sent to a swimming pool twice a week. I would go there without demur and I actually did quite well, even though I was the smallest one there. I became the instructor’s pet and I even thought about joining a swimming club, but, unfortunately, that would have been too engrossing in the face of my dad’s illness. When it came, I would sit in my room with music, books and a sheet of paper. The only place I would go out to was the swimming pool, which was my form of escape. I understood a lot. Intuitively, of course…

BD: Did you understand that your dad’s disease was fatal?

KK: I never knew he was going to die, but I could sense something wrong was going on. I knew next to nothing about the disease. We had a computer at home, but there was no Internet connection, because my artistic parents had no heads for technology and were a bit old-fashioned in that matter, even though it was already 2001. Together with my mum and sister, we looked after dad. I used to help around him and in the evenings I went to the swimming pool, where I literally had those five minutes for myself. That’s where I could submerge. As you can see, I am always feverish and take everything very emotionally and swimming cools me down. And, in a way, it also helps me distance myself from the outside world. The swimming pool was my protection. The rhythm – the elation, the flight and rebounding off the walls. It’s like a mantra. Besides, doing sport releases endorphins, so it’s recommended to people who experience stress. On my way back home, in my thoughts I could still be at the swimming pool, because I have a photographic memory. I do not bother recreating photographic images of what I have seen though, but I am able to recall a detailed picture of the atmosphere instead. Whenever I couldn’t go to the swimming pool, I would return there in my drawings. And then I saw Hockney. I was really fascinated by his mastery of drawing. I often return to and never really close the albums with his paintings. People have always interested me as well. In my paintings of swimming pools, it’s a man that’s most important, a man and his flight. And also what water does to a man when he submerges. Not everyone is fond of a swimming pool, but for me it’s a very important place, my own space.

BD: Is it still a kind of shelter? An escape?

KK: Not even that. It’s a place where you collect your thoughts. I think everyone should have a place of that kind, a place where you go when things are bad or when you have some thinking to do, when something has happened, something hurts or seems to be too complicated. It helps me to be under water. I generally like apnoea, because it triggers something special in your body. Another thing is that when you swim a lot, your lungs are fitter and you don’t need so much oxygen. Underwater I am alone, completely alone, distanced, and then I remember things, my thinking is intense, but not necessarily logical. It’s a kind of place where… I wouldn’t call it a prayer, but a sort of… therapy.

BD: Cleansing…

KK: Water has always got that cleansing effect on me. I associate it with washing off dirt, breaking a spell of bad moments, undoing bad spells. Swimming pools lure me. There is something inviting in them and I have this constant desire to jump inside and have a swim. And, thus, I often go back to the theme. I simply feel the urge to paint swimming pools once in a while. They are changing with me. Once they were gloomy, but now it’s gone. Nowadays I started noticing swimming pools with landscapes. Recently I have been painting a new series of triptychs, which resemble film frames. I often paint series, just like a film reel, because – apart from painting – I am really into cinema. As a child, I wanted to be a camerawoman and I told stories about children. Nowadays I also tell stories, but about my thoughts and dreams. In those triptychs of mine I try to tell, for instance, a story about a swimmer. At first, the swimmer is in water, then he rises slightly above its surface as if he was flying over the swimming pool, and finally he disappears and we are left only with clouds, those strange, graphic clouds that I noticed over the housing estate of Salwator in Kraków.

BD: Your paintings are of a reductive type, devoid of any detail, ideological. What is a painting to you, actually?

KK: It’s a difficult question. I think it easier to say what it is not. Above all, it’s not meant to reflect reality. Precision and decorativeness is not important either. I am not into detail, because I do not create a painting to show that something is pretty. I do not want to show off. Sometimes details are necessary, but I never paint details just for the sake of doing it. The most vital elements of a painting are its atmosphere and story. Although you don’t have to tell everything in the right order. I have recently realised that it’s worth reducing paintings, because it makes them stronger. I do like painting people and I feel tempted to draw every single face I see. I know a lot of faces that I would like to show. Relationships are also important. But, sometimes, when a face turns and I see a new detail or when I decide against painting some details, something else floats to the surface. That’s why I occasionally skip some details, to stress something else. Colour, atmosphere, shape.

BD: But you are not much of a colourist. You usually go for not really colourful and more muted hues – browns, greens and blues.

KK: Still, colour is important for me. It’s not about the painting being colourful. I instinctively choose those hues that ‘sound’ better to me.

BD: So you prefer tunes with fewer notes, right?

KK: Not necessarily…

BD: But when you reduce colours and details, you seem to be limiting yourself. Are you heading for synthesis?

KK: Maybe, subconsciously… In some paintings you can notice limitations – the subdued colours, the reduction of their form. That’s why I sometimes fail to put everything I want to say in one painting and, as a result, I paint series. On the other hand, however, I also have paintings that are full of details and stronger in colour.

BD: I still believe you knowingly cultivate primitivisation. When I first saw your later paintings, or even the first ones you created, I found them slightly clumsy and awkward and thought that maybe you lacked skill. But now, when I see your drawings, I know that you lack no skill at all and that the simplification of forms does not stem from the lack of ability, but from a conscious desire to paint this way. There are painters who graduate the Academy and still can’t paint, but you are definitely not one of them. You’ve chosen this way purposefully.

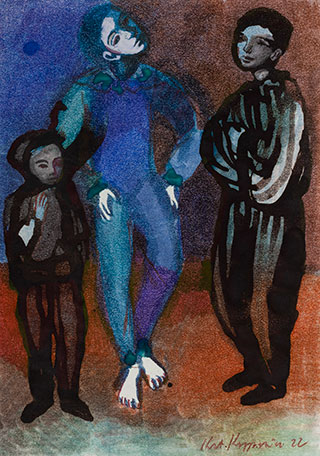

KK: Perhaps… Still, I think I did learn quite a lot in the Academy. I truly studied there. I conscientiously did all the tasks, I attended my classes regularly. Every half a year I would change drawing classes to something else, e.g. I spent some time on a sculpture course. My diploma work was musicians painted from nature. People from the Music Academy used to come to my place and I painted them while they were playing. It was a very realistic study of figures. I considered it to be an interesting way to do something in the style of Balthus – to prioritise the observation of reality. Later, however, I realised that Balthus’s reality was substantially modified by his outlook on the world and that he used his own expression. If he wanted, he could paint women realistically, but that’s not the point when it comes to painting. Naturally, not everyone approves of that and one could even say that he made a mistake when he painted someone with a huge head. This kind of inability you will also find in Wróblewski’s works, as his figures have that stiffness about them, but when you look at his works in ink pen or brush, you realise what a great drawing artists he was. My figures are also stiff – they are perceived in a different way than it normally happens.

BD: Is this a kind of filter, spectacles that you wear to scan reality and to make it look different in your paintings?

KK: Painting a man from nature and painting his essence is a completely different story. It’s not important what you see, but what you know about the person. It’s the Japanese, i think, who claim that one should not paint a tree, but paint ‘treeness’. I could paint people they way they look like, but the act of painting itself leads me somewhere else – I reduce, change and – at certain point – some of my figures become stiffened and some more natural, but this is a welcome effect. Take Beckmann – those black, linear silhouettes of people that blend with yellowness or the colour of their bodies... It’s not a problem and, actually, it seems to be the righter way… For me, the best thing about painting is that you can practically do whatever you want.