Bathtime with Blake

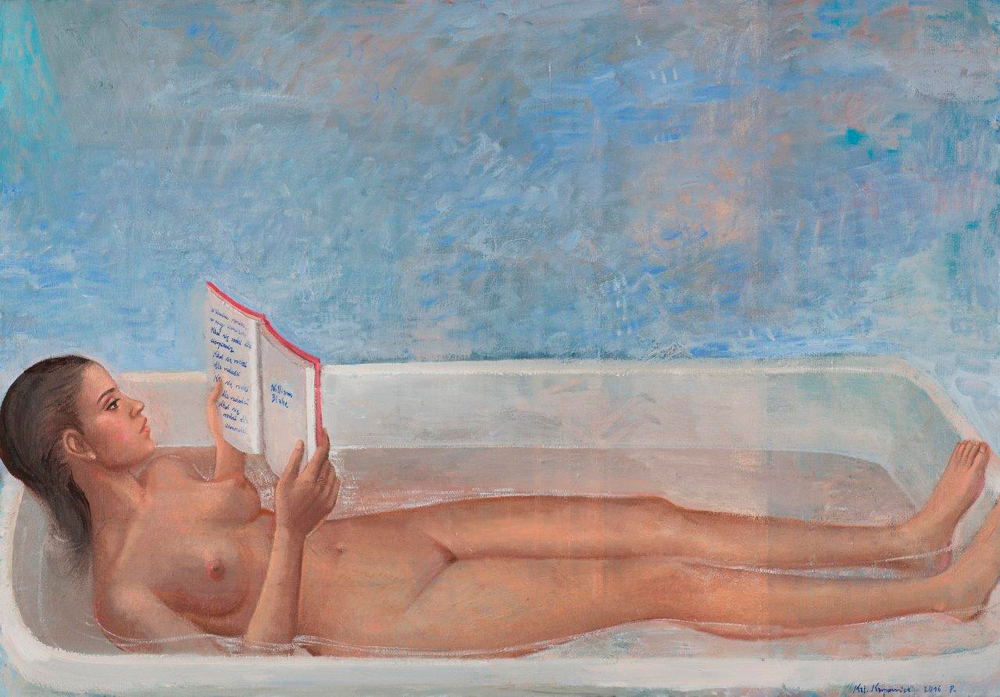

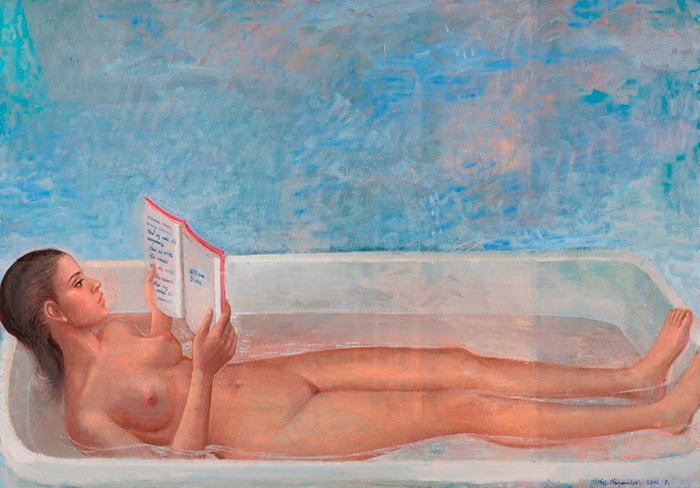

Among my many quirks, the most important is that I always took baths with William Blake. As far as the works I chose are concerned, it varied. Most often, I think, it was Milton. Milton was pure art, literally.

On the strangest day of my life, I did it, too — I undressed, stepped into a bathtub full of hot water and picked up Blake. There was a gale outside the window. I always heard it clearly. I lived in Kraków, in Dębniki, on one of the streets as narrow as a scarf, so tight that the trees were barely squeezed in between my townhouse and the next, on the opposite side. In the wind, their branches knocked on my windows like the damned, so strong that it felt like not only all the pots in the commode rattled, but also all my paintings, the ones on the walls and the ones on the easels, waiting to be finished.

I had been lying in the tub for half an hour, the water covering me like a warm blanket. I was alone with William Blake. The truth is that I was always alone with him. William Blake was my best companion in life. The only one I had.

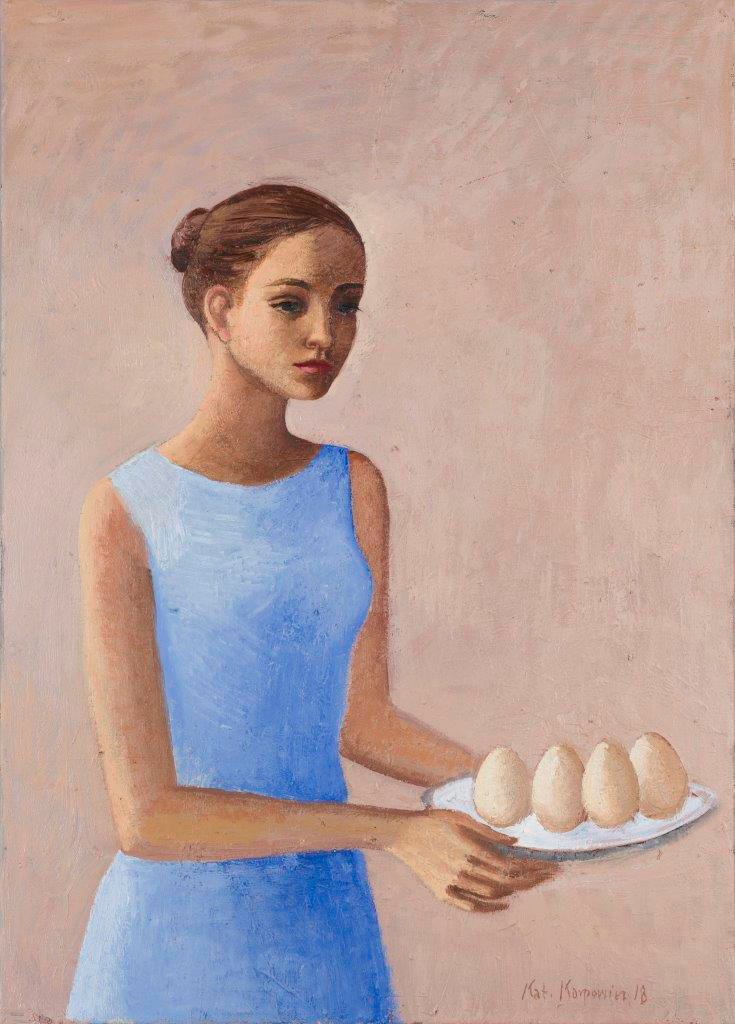

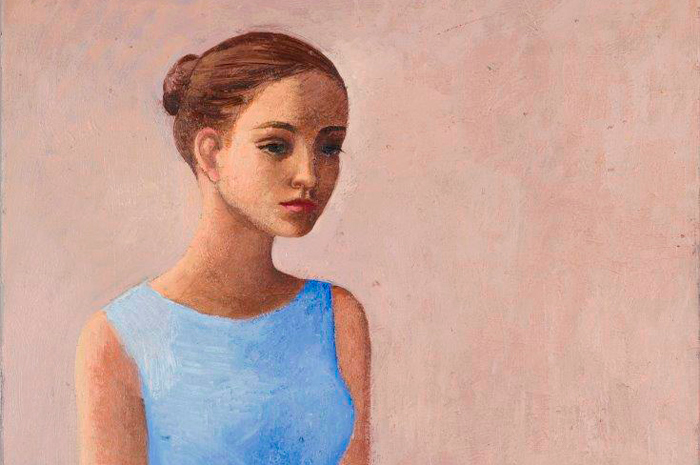

Sometimes, I pretended things were different. In the morning, I put on my favourite dress the colour of the sky after a storm, made four soft-boiled eggs — four is a number adequate for a perfect family — and carried them to the table like a circus performer, calculating the exact steps, ensuring the rhythm and precision, finally putting them on a table covered with a starched tablecloth and eating them — as if I was eating my sadness, in carefully measured white-and-yellow doses, and each bite would get stuck in my throat, like a piece of an old duvet. Four eggs, including three for my non-existent loved ones, disappeared in my mouth as if it was a long-practised trick. Then I sat at the table, still like the life in my latest painting, worrying not only about my future, but also my cholesterol.

One Hundred Years of Solitude — I always regretted that this title was already taken; it should have been the title of my biography.

I sighed heavily and closed my eyes for a moment. The watery blanket wrapped me tightly, I felt like I was small again, like the head of a pin, floating in my mother’s amniotic fluid, bouncing against her pancreas and liver — how often I wanted to go back there, complain about being pushed out into the work, into Dębniki, straight into the storm, straight into all the inflammatory points of the city, the landscape sitting there behind the glass like a monster; it was raining outside the window, the raindrops rhythmically hitting the window panes.

When I opened my eyes, I was sitting alone at a wooden table, in a completely empty room. In front of me, on a plate, were rowanberries, red like a toreador's costume.

“Put on a mask,” said one of the rowanberries in a voice that sounded like it was coming from inside a well.

I looked to the right, at the wall. There were many masks hanging there, in different colours, thin and delicate, as if they were made out of crepe dough or — I started to worry — human skin. I grew frightened and started to protest.

“Why? I don’t want to. Why can’t I just be myself?” I asked more amicably and suddenly understood how little that means. My faces seemed to me to be an apple that fell out of my hand and rolled somewhere far out of sight.

In order to, as they say, find myself, I looked into the eye of the mirror that stood on the table. I was copper-gold, like fish scales. I got even more scared — I didn’t see my reflection in it. The longer I leaned over it, the more I wasn’t there. The reflections in the mirror were masks, which I realised hung everywhere, on all the walls, a festival, a carnival, a horror of masks that suddenly surrounded me like a wolf pack and pierced me with empty gazes, twisting their faces in a rubber smile.

The rowanberries laughed maliciously, hissing. From this thunderous laughter, the masks on the walls began to move. With a trembling hand, not looking at them, I reached for the nearest one and slowly put it over my face.

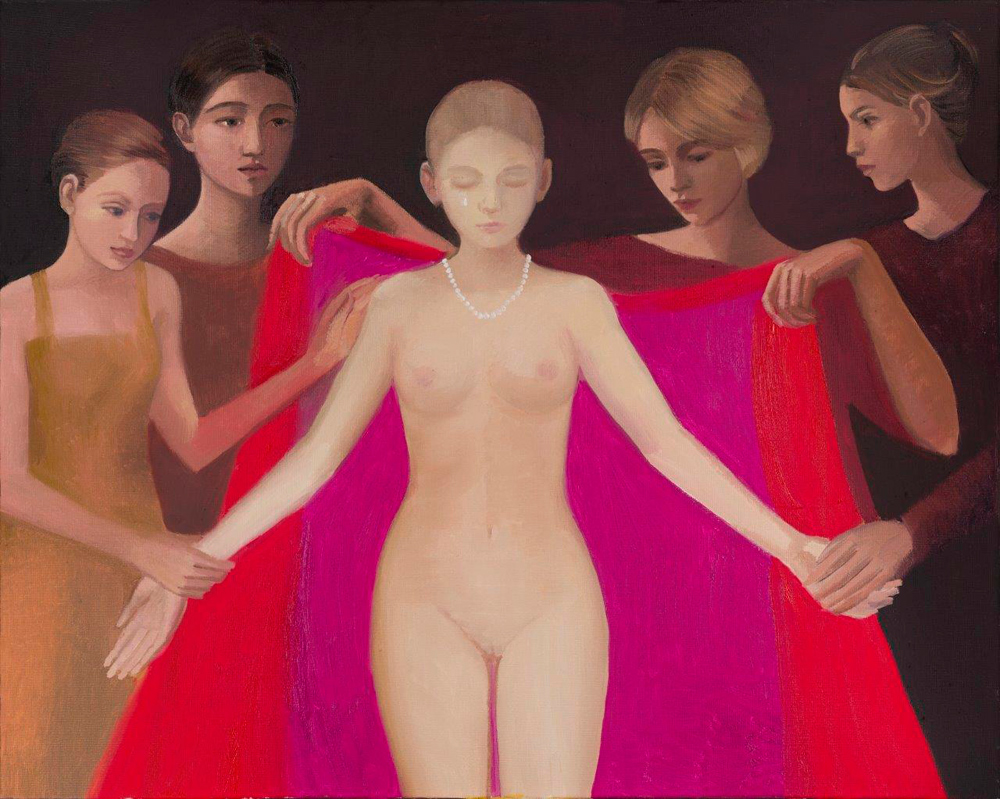

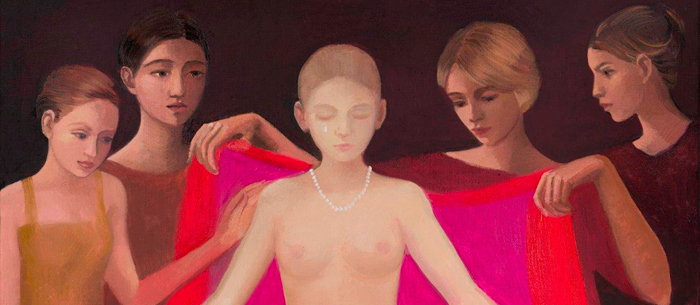

When I looked through it, I was standing naked in a completely different room, other women dressing me.

“They will bring you wooden shoes for the wedding,” one of them said and with a gentle movement of her hand took the mask off my face. I wondered what was in its place now — I wouldn’t be surprised even if I wore the moon around my neck.

“The bridesmaids have been waiting in the orchard since the morning,” said another.

“The trees are white, and white are their dresses. At noon sharp, all of them will take off their masks.

“Those two grew on the trees,” said another one, anxiously, as if it was a warning. She had such a strangely pinned chignon that it looked as if an animal was sitting on her head.

“Two cousins on old pear trees. They will pick the fruit, and they will collect them all,” the oldest one said roughly.

“One more lies naked among the bushes,” the youngest one whispered, but she fell silent under the punishing gaze of the old one.

“It’s time, it's time. They’re finishing the chess game!” the one with the chignon on her head said feverishly. They took my arms and led me to the next room; I only managed to have a quick look at myself — there was no trace of hair on my body. I was naked and smooth like a fish.

They stood behind me and put a velvet cape over me, its colour reminiscent of a split pomegranate; I don’t want to say anything, but in a way, it reminded me of Christ’s robes, which scared me again. I looked around in a panic to see if there was a cross there.

“Not on the cross,” the youngest one giggled. “If anything, on a bull’s horns.”

“The others grew on the trees for her,” the old one said, cutting off the conversation. As I understood, it was supposed to console me.

They wrapped me in this red robe so that it looked like a dress; pulsing with the colour of blood. They put a black bull mask on my face, decorated with a colourful garland of fresh flowers; there were drops of dew on some of them, tiny and glittering like pearls. Then they led me to another room. A young man dressed as a toreador was already waiting there — he looked as if he had just woken up from a deep sleep. His face seemed familiar to me. I stared into it stubbornly, as if into a solar eclipse.

“William,” he said. “William Blake. I like eggs, too.”

I opened my eyes, as heavy as if weights had been attached to each eyelid. William Blake — in the form of a book — was floating in the tub like an undiscovered species of fish. Piscis papierus. I slowly got up and out of the bathtub. The storm had just ended. I breathed deeply and looked down. And then a small rowanberry, red as bull’s blood, rolled under my feet.