The complementarity of contradictions

For a long time, it has been maintained, that all key attempts in 20th century art have already been made and realized during the era of early modernism while what has remained is only an epigonist repetition or at best an eclectic variation of those attempts. If this were really true, long before “postmodernism” and the formally modeled works of “political correctness” of the last century, all other innovative trends would have to have the prefix “post” affixed in front. However, things are not so simple. In truth, no formal sequence may be excluded only for the reason that all of its possibilities have been exhausted. The concept of “everything” does not exist with respect to the intellectual and formal possibilities of man. This also applies to man as artist whose possibilities are unlimited and deconstruction is always simultaneously a form of construction or at least it should be (F.N. Mennemeier).

Such an attempt at “deconstruction” is made by Małgorzata Jastrzębska who utilizes in her works elements which are particularly popular in abstract art (circles, stripes, triangles, lines, spatial forms), analyzes their relationships – their mutual diffusion or repulsion, complementarity, cohesion or lack of cohesion between the vertical and the horizontal, superposition of one form onto another, retraction or fading of space as well as the collapse of perspective. Vibrance spurred by the use of a multitude of forms which allow for a variety of possible interpretations appear to be in the end a type of ordered chaos. Something similar occurs in real life where we are attacked by a multitude of visual messages and signals emitted by our surroundings. The messages and signals that do reach our minds are those which possess the strongest messages or are simply the most aggressive in nature and to whom we surrender subconsciously. The same is true of a painting – we absorb what is dearest to us (this can be a form, color, thought, mood, feeling) or we succumb subconsciously to aggressive expression.

Małgorzata Jastrzębska gives us the freedom to choose by connecting in her works elements of constructivist thought with the irritation of op-art, the balance of geometric abstraction with a futuristic momentum. As a pretext to play with form, depth, and space, she uses the geometric shapes of lines, circles, and rectangles. An important aspect of her painting style is color – something technically boundaryless and difficult to capture – something that man needs to assign form to through systematization and subordination. Since, as someone had already noted earlier, light is the most important color, one can perceive this color in these paintings, even to the extent that one can be blinded by it. Light, being the fruit of some but not other mixtures of colors, elicits additional meanings from these paintings.

Despite the wealth of utilized elements and colors, their shades, and shades of shades, Małgorzata Jastrzębska’s own system of creating order is based on reduced form and her personal emotions associated with this form are subject to strict control. I do not want my feelings to be apparent in a painting. I tend to want to liberate the feelings of the viewer in order to give him or her something different – something besides aesthetic pleasure –

states the artist. This “something different” is the inducing of reflection which arouses the imagination and feelings of the viewer, persuading him or her to go deeper inside oneself. The most often used principle of central composition and its associated centrifugal and centripetal elements allows one to think that the artist herself, turning her attention to her inner self, wants that “something” to touch her in order to subsequently reject it. The impression of motion in her paintings is usually only an appearance and results from the way that color is used and the unique interaction of geometric forms permeating each other, creating an optical illusion of concavity and convexity. Despite the objectification of the painter’s theme and plan as well as systematic actions, it is difficult to not notice emotions here. An earlier statement by Frank Stella who, much like Jastrzębska, believed that in his paintings only that can be perceived what is really there

, does not sound credible. Feelings are important, although what is also important is the thought derived from technique. These two things must work in unison. Emotions cannot be hidden behind definitions.

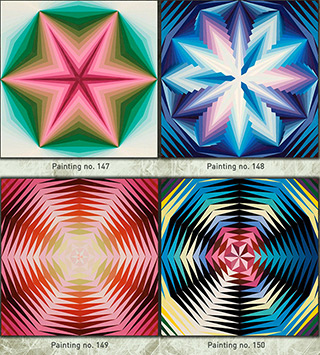

The vast majority of the works of Małgorzata Jastrzębska, thanks to powerfully structured forms of sharp contours and divisions as well as flat patches of hue, possess an unprecedented intensity. This applies even to smaller pieces of her art (which utilize forms reminiscent of a rosette). This effect is multiplied through the use of unequivocally central composition, as in Painting no. 160 and no. 162. On the other hand, Paintings no. 147-150, thanks to the use of complementary or derived hues of varying intensity of rose and red as well as blues in harmony with black and white, are quite irritating, although this irritation can be attenuated through the gradual use of color intensity and clarity of form. However, the intensity of color effects does not necessarily have to be the result of its degree of saturation. Sometimes, that which is less perceptible, is more intriguing. That which is not fully expressed also allows the viewer to participate in the on-going “creation” of the painting. An example of this, reminiscent of a fan, can be a fading form of rose of subtle tone in Painting no. 169 and no. 170 which mysteriously peers into the grey background of the plane of the canvas asking a silent question with its own lack of response. This is why this remaining physical “minority” is no less important for this very reason. Aesthetically refined pieces of canvas, marked by a lyricism of responses and a monochromatic poetry of painting, persuade one to think. And they evoke feelings in the viewer. Some of Jastrzębska’s paintings are somewhere on the line between great divisions, connecting both harshness and softness, peace and anxiety, darkness and light. One of my favorite of Małgorzata’s works is one of those “minority” works – the monochromatic Painting no. 135 – a square canvas divided into nine mutually permeating circles where color, victorious over the formal austerity of structure, delicately builds the painting. Its color scheme, maintained in broken tones of rose, purple, blue, green, and yellow, as if it were a musical composition, attenuates the severity of thought with the subtlety of feeling.

The French writer Anatole France noted that talent is only a form of persistent patience

. Małgorzata Jastrzębska, disciplined and systematic, which is confirmed by the carefully planned construction of her paintings, is patient. This is also confirmed by Painting no. 130, which brings to mind the op-art experiments headed by Victor Vasarely. Referring to the painting Shining from 1965, done by another representative of this school of art, the American Richard Anuszkiewicz, the Polish artist gives it a new meaning in 2007. Optical irritation, caused by Anuszkiewicz’s use of straight lines that draw attention away from radial lines (or vice versa), in the case of Jastrzębska is the result of the addition of patches of hue scattered freely all over the painting as well as shades reminiscent of depth, located on the right side, and destroying the rhythm of radial lines. The automatic nature of this work, disrupted by a sudden formal solution, gains a new dimension, making the drama of the message deeper.

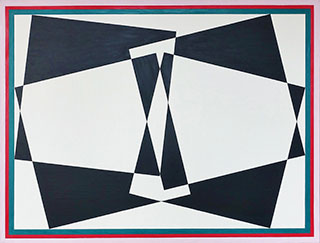

Contradictions in the paintings of Małgorzata Jastrzębska do not have an antagonistic effect but rather a complementary one: concavity and convexity, darkness and light, heaviness and lightness, harshness and softness, all work in unison, in accordance with the fundamental principle of classic Chinese philosophy: yin and yang. Just like in Black and White, one of the most recent works by Małgorzata, one can to some extent feel this mutual dependence. A contemplative peace, a color scheme reduced to two contrasting yet complementary hues, arouses in the viewer a certain type of anxiety. Could we change something in this painting? Perhaps remove a certain element or color, or maybe add one, in order to disturb the complementary yet disquieting balance. However, if we choose to consider that the mutual interaction of the yin and the yang is a natural cause of all changes, then we can regain our lost peace. The rethinking of all problems anew in light of new circumstances is still possible, sometimes even necessary

– stated George Kubler. Following the path of the oldest idea in Chinese philosophy, manifesting itself in all branches of science and art, we will become convinced that constant, timeless values cannot be called pragmatic or epigonistic. Unless we want to view them as “post” yin and yang.

Essen, February 20, 2008