Report from the Last Judgement

As Leszek Jasiński was graduating in 1988 his studies in the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, it seemed that his career would develop quite fast. Before he chose an ‘outsider artist’ life-style, he managed indeed to partake in several artistic events which became famous at the time (the late eighties). Those included an exhibition at the pavilion in Foksal street, a joint event with Mirosław Bałka. Jasiński presented there Adam and Eve as a pair of a boy and a girl, wearing Soviet ‘pioneer’ (scout activist) uniforms. Together with Robert Maciejuk, Mirosław Maszlanka, Anna Myca, and Witek Kucharczuk, he organised open-air creative-artistic sessions at Otrębusy. Those presentations of ‘post-painting sculpture’, held with a real flourish, heralded the coming of installation art of the nineties.

Yet shortly afterwards, Jasiński was not making official exhibition appearances any more. A pity, that, for his works of the recent decade have shown that not only did he drive his artistic gifts onto an individual and lonely path but also made an existential experiment on himself. He namely left the town he had lived in, and settled in a rural area. He broke-up most of his social and artistic contacts. He got incorporated in his new surroundings as if he was willing to equal his Modernist ancestors (of the turn of the 20th century) in a life-style of this sort. The first, and not infrequently the only, viewers of his sculptures became those local peasants and communal officials who could afford ordering a portrait at the Jasiński atelier.

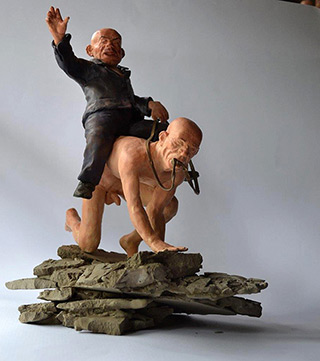

Leszek models his figures with clay and often dresses them in his own shirts. He inserts cigarette butts into their mouths, and uses a lipstick in order to add colour. His sculptures are not monoliths of a durability devised to last for centuries. Humanity is not made of bronze, it is conceived out of cheap materials. Clay which usually serves sculptors for making bozzettos, i.e. ‘sketches’, appears here as the final material. For dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.

As is the case with any art, also today’s plebeian art has its own decorum principles. Clay and concrete, the latter as painted with joyous colours, have occurred the most proper materials for it; the most demanded style being extreme naturalism whose irony has turned out entirely indecipherable in that rural environment. Jasiński’s observations are a far cry from picturesque images of the countryside which artists adhering to the ‘Young Poland’ movement (Polish modernists) conferred on us. The artist shows physiognomies, detected in the vicinity of a countryside grocery, in the likeness of those of Brouwer, Teniers, or Rabelais. Physiognomies being deformed by alcohol, wrinkles, or warts.

To a townsmen’s eyes, those appear distastefully provocative. Their naturalist appearance seems to be sneering at any models, and vice versa: those images, positioned on quasi-Classicist plinths, or incorporated into Classic themes such as e.g. Bacchanalia, seemingly appear a plebeian deriding of the ‘lofty’ art. Has Mr. Jasiński become part of this world, or has he positioned himself at a distance from it?

This artist would do anything in order to render unfeasible for us to resolve on whose side he could possibly be. For Jasiński appears not only to be an observer but also a participant of that plebeian life. Even his house resembles a rural hut, ‘heavy’ in terms of proportions, rather than a fashionable manor with a colonnade; it was built only ten years ago but already has become caving into a boggy ground – it was being constructed, after all, according to a ‘farmer’s method’.

Van Gogh was of opinion that peasants should be painted as if the artist were one of them and as if he thought in the manner they did. Yet Leszek is not going to teach his neighbours the Gospels, or make any attempt at instilling urban aesthetic solutions in their environment. His temper would rather lead him along the road of Céline’s character Ferdinand Bardamu who perceived life as a tragicomedy both disgusting and humiliating to a human being, one ripping a thin layer of moral principles off the humans. Where has Leszek been led by his own Voyage au bout de la nuit? What is the unique quality of his work all about?

Leszek did not discover naturalism. Instead, he has employed it, somewhat perversely. He certainly has an inborn talent in this respect. The other source of Jasiński’s art is religious art. His scultping compositions owe much to the spirit of the Baroque. They speak of things ultimate. The elation and pathos of the religious scenes clashes against a motion-picture-like love for detail. Leszek builds scenes with a few dozen figures/figurines, dealing with them like a director of a box-office-success movie would do with the starring actors and crowds of extras. And so, he arranges the main takes, and cares about details which saturate the work-in-creation with the truth of life. These details are often drastic indeed. Leszek prefers to confront us, the spectators, with whatever we should not otherwise be willing to view: mundane stuff, ugliness, and cruelty. In the way he works he may to some extent remind us of Goya with his Los desastres de la guerra. So, he has exposed us to such a discomfort; in the name of what, namely?

Or perhaps that fleshliness is not any burden whatsoever? Perhaps this corporeity may not take the viewer away from ‘things higher up there’, since there is nothing for one to be drawn away from? Because in that vicinity of the locality of Otwock (not far from Warsaw) where Leszek has settled down, there may be nothing but the plain truth of the matter. This is simply the way that world, this world, is. Its triviality, coarseness, and bluntness are as perennial as a bronze monument may be.