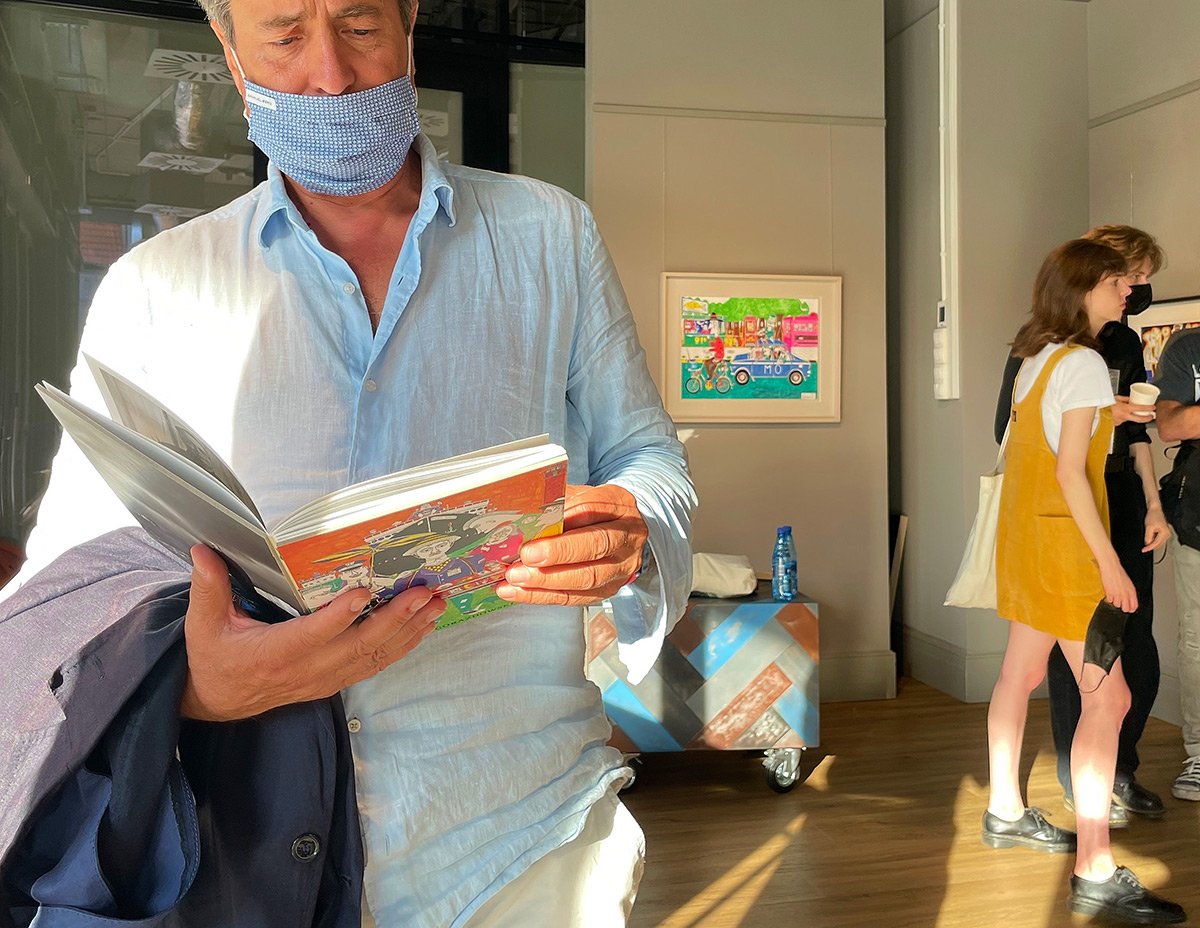

Cumulative stimulus study

“There’s this guy, Wiktor Gorazdowski. He makes cool drawings”, Edward Dwurnik told us a few years ago. The young artist sent him some works for evaluation. He sent them to many painters, here and there, a little blindly, building up contacts on his own.

A man from outside the community, untrained, an amateur, self-taught, whatever you want to call it. In any case, a non-professional artist who wanted to see if he measured up to the professional world of art. After all, who said that the lack of a formal education is an obstacle? It is not the diploma that makes the artist. Even Joseph Beuys said, “everyone is an artist”. Some more than others.

He made the right choice because Dwurnik immediately recognised his skill.

After all, his own work was based on a fascination with the painting language of Nikifor, the greatest naïve painted of Polish art. And in Gorazdowski, it is easy to find a lot of attitude à la Nikifor.

He is an outsider with a strong need to create. In this way, he expresses himself, tames the world, communicates with it, as well as practicing a worldview. The latter in turn links him to Dwurnik, who constantly commented on reality.

And here the similarities end, because Wiktor Gorazdowski does not imitate anyone – the similarities come from the attitude towards art.

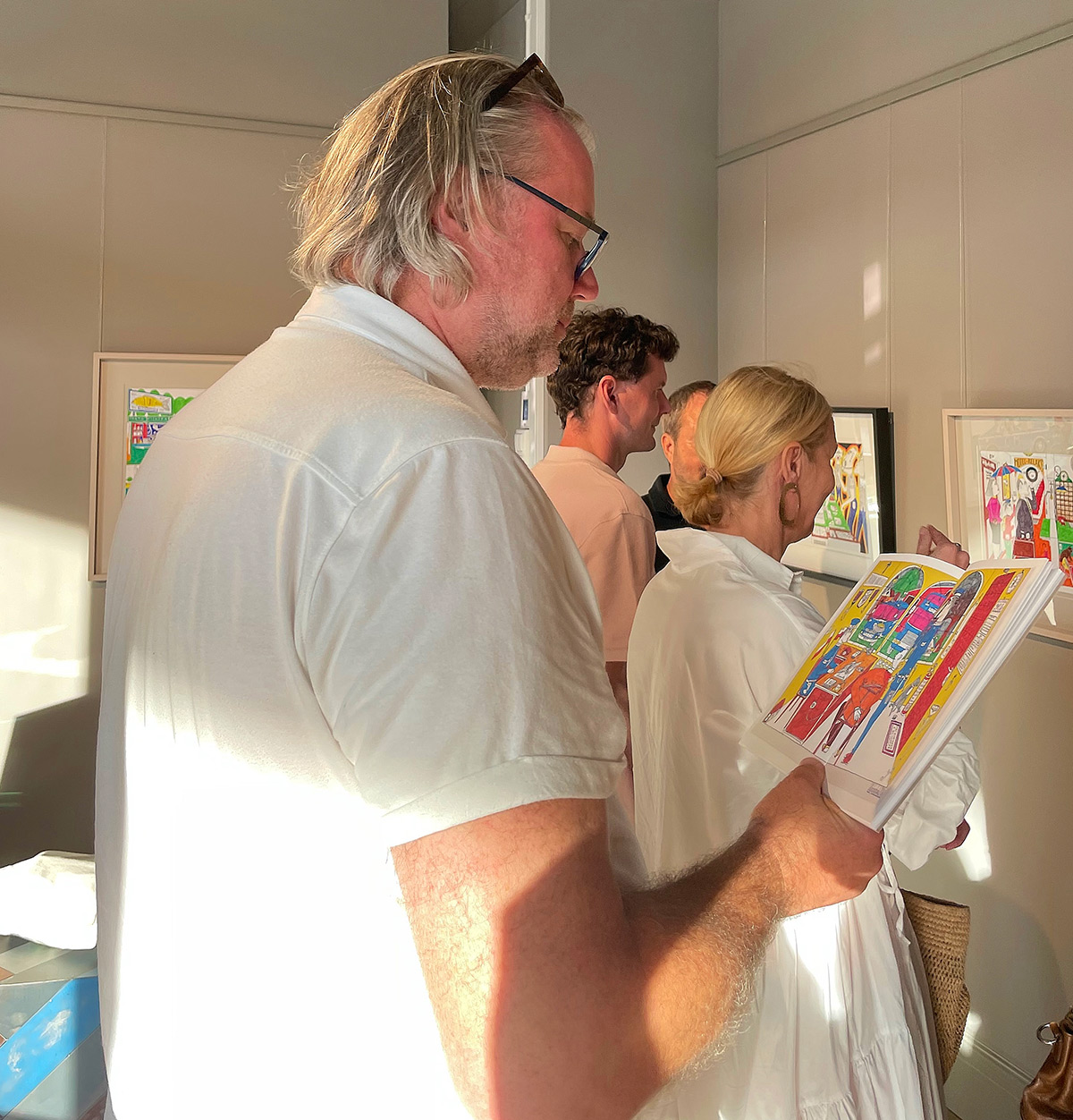

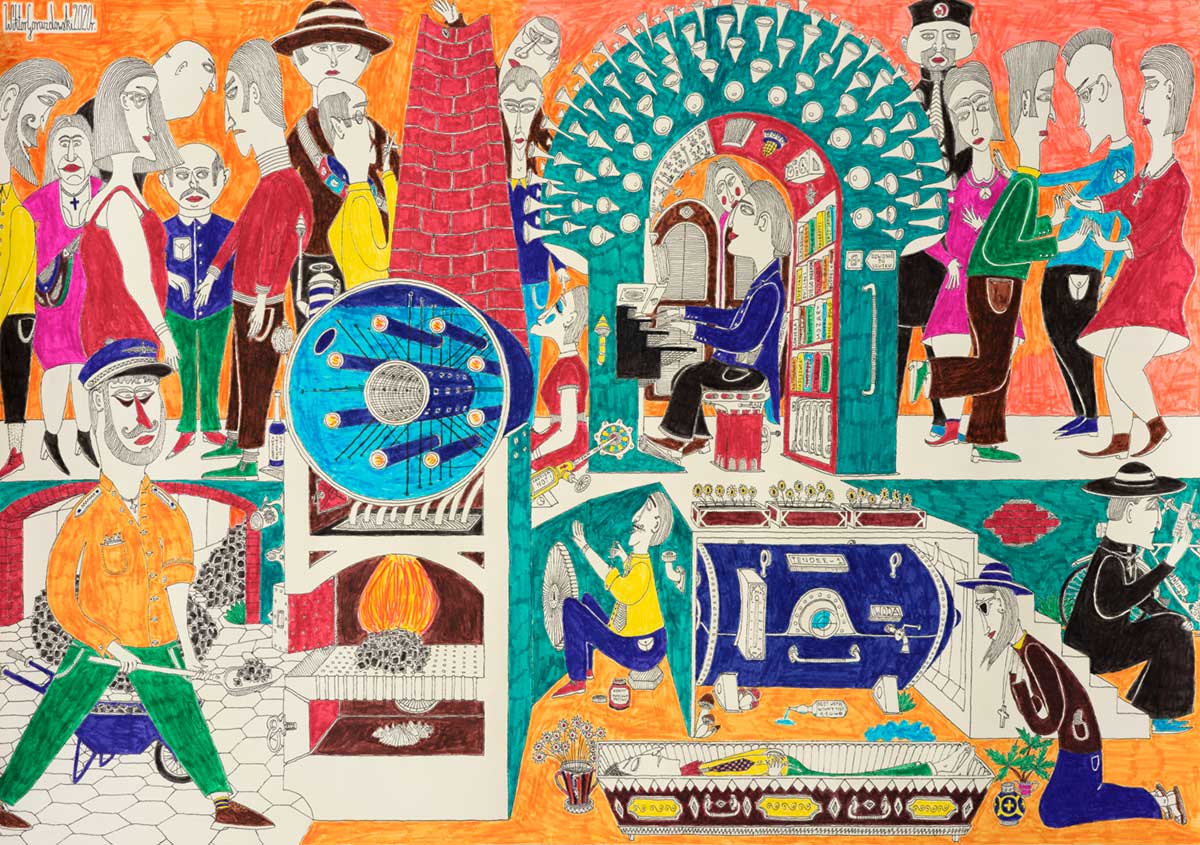

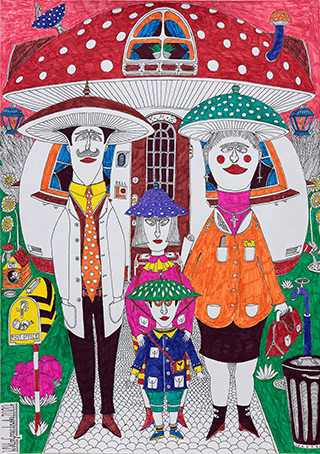

Gorazdowski has his own individual visual language. Characteristic, refined, and consistent. One that would never pass any exams at the Academy of Fine Arts, but again, so what? The artist applies his own rules of perspective and his own rules of constructing a painting. He draws everything out, with an engineer’s precision. He fills in the outlines with colours; he likes to use markers.

He likes to tell stories, his works are extremely narrative, often with a second or third hidden meaning, and the artist is a witty narrator: even in difficult or painful scenes, he can sparkle with humous, unmask taboo subjects. Reality as he makes it becomes surreal – or perhaps that is simply what it is.

With the bent of an engineer, he creates fanciful machines and devices. They are bizarre, like those from the novels of Raymond Roussel, an outside of 20th-century literature, a favourite of surrealists, whose wind-powered clock or sun and wind-powered pile driver are meticulously described, down to the most minute details of construction and operation.

In Gorazdowski’s works, too, everything works according to the rules the artist-engineer established. We need look at the drawing depicting the Osmilogic Chessboard, inspired by the famous Mechanical Turk, an 18th-century invention, seemingly a brilliant machine but in fact a clever mystification, to which Gorazdowski introduces his own innovations. “The technical solutions I propose in this device are prototypes”, he explains, “but, importantly, they offer a real chance to build such a structure and to operate it properly. To improve the readability of the cross-section, the drawing will contain descriptions”.

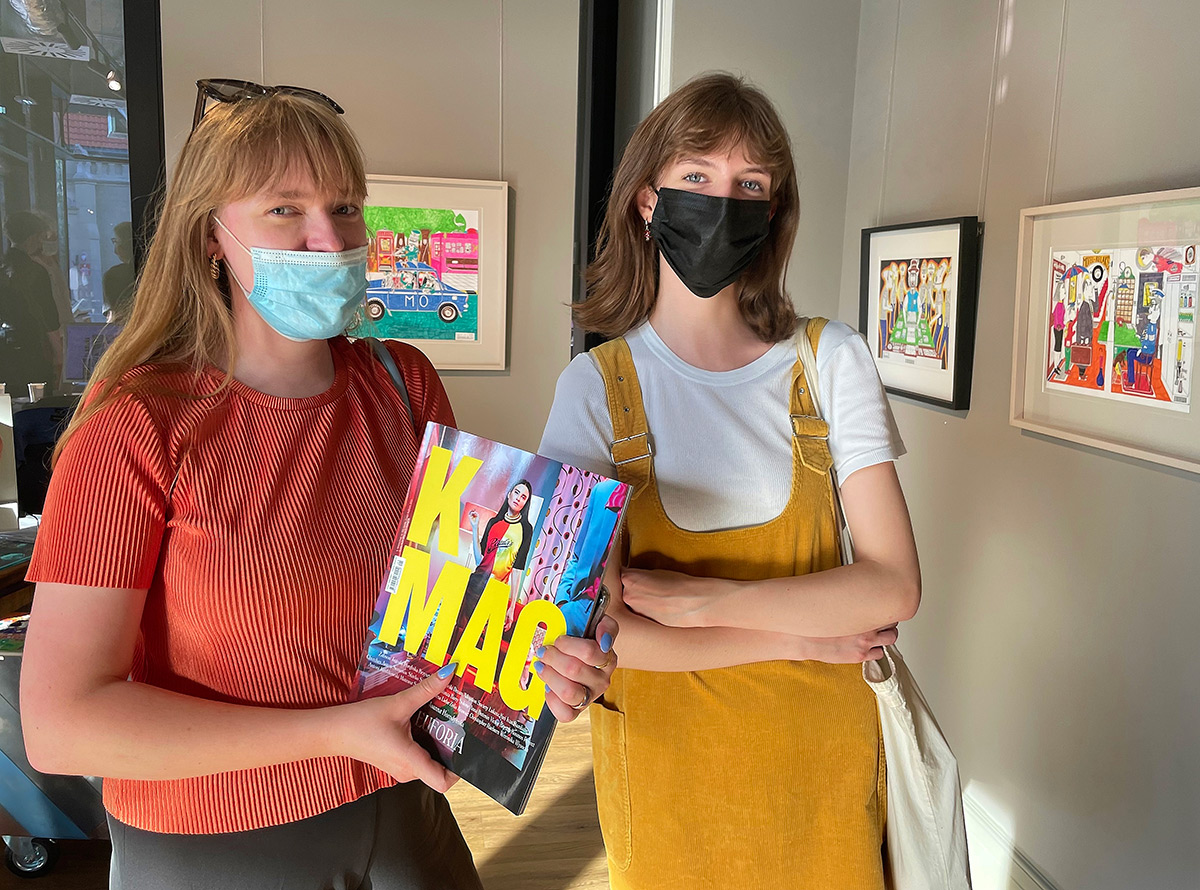

In the catalogue to Wiktor Gorazdowski’s first solo exhibition, the drawings are accompanied by literary miniatures by Tomasz Wiśniewski. It was our dream to bring these two artists together in this book.