The Sepia Europe

A few years ago one of my acquaintances, a modern art and historic objects collector, showed me his last trophy he had bought from a Viennese antique dealer. It was a collection of old photographs. Over the several evenings that followed, we watched them together through a magnifying glass, scanned them producing maximum blowups so that we could see any and all details. It was fun, to an extent, but we wanted to solve the puzzle on the occasion.

Anyone who saw Antonioni’s Blowup knows that photography, that apparently simple medium, often has a ‘double bottom’ to it. As a next step, we showed the copies to Bogna Gniazdowska, an artist whose paintings are based on use of photographs. Bogna is so well versed in the remote age preserved in sepia pictures.

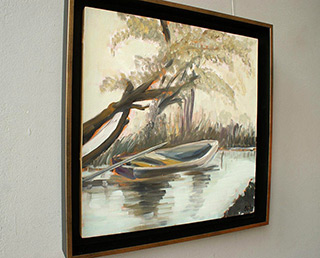

The exhibition The Sepia Europe consists of a cycle of Bogna Gniazdowska’s paintings made after photographs taken in 1913 to 1915 by Jan Kotik, the official photographer of the Austrian-Hungarian army. Kotik’s optics tries to keep things at an official distance, giving an objective and unimpressed picture of the k.u.k. Army’s ramble across the Balkans. Today, Bogna singles out individual figures out of those pictures; she emphasises their personalities and penetrates them, and completes their images with what might have escaped Mr. Kotik’s attention or, what was not, to his mind, part of the official mission standard. The Kotik photos are virtually deprived of any emotion, human relations; very scarce are any casual captures or details that can tell you more than any studied pose struck or a carefully arranged composition. In their static appearance, pictures by Kotik are remindful of the famous August Sander photographic cycle Antlitz der Zeit.

How does Bogna intervene, then, and what does she complement any such picture with? There is, say, one of the three nun-nurses serving at a field hospital, all of whom appear imperturbably monolithic as portrayed by Kotik, and she is all of a sudden given a thin red thread and loops it around her fingers. A disturbing and humanising element, that: some fun, apparently, but there’s the disconcerting redness of the thread, triggering an association with a thin trickle of blood that suddenly shone up between the girl’s fingers. The radiotelegraph operators pictured are working tensely, as evident by their faces and the way they are deployed, whilst in Bogna’s painting, they have fallen asleep: their eyes closed, bodies laid back, as if they have heard in their headsets a sweet voice of a Christina Aguilera, today’s diva of the armies, instead of the usual impersonal beeping.

Does Bogna abuse the past, or rather, gives it a second life? I hope this exhibition will disturb you much in the way it has already disturbed me. Rather than giving answers to any of your doubts, it will pose yet another question: about the mutual relation between the worlds of Yesterday and Today.