The beauty of the past

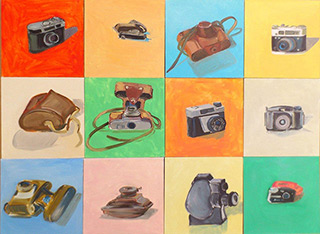

Bogna Gniazdowska has found her original method of how to paint the Past. She practices an interesting variety of historical painting. What are all those numerous portraits, forming a panorama of the past, after all? What are those properties appearing on the paintings? On preparing himself to the act of painting, Jan Matejko used period objects of relevance. He collected them. Nowadays, it is the twenty-first century, and a painter like Ms. Gniazdowska deals to a greater extent with documents such as photographs. But first of all, she wants to have to do with them. She is a collector, too. She draws her characters into her own world, in line with her own vision and plausibility of occurrence of relevant colours in that world of yore, now lost.

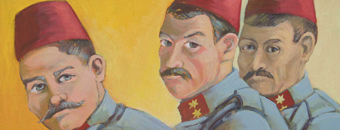

The photo NCOs canteen displays a man in an Albanian hat. The painter has multiplied him, and added an ardent colour to it, reinforced by the orange-and-yellow background. Is this really the way we, people of the North, see the Balkans?

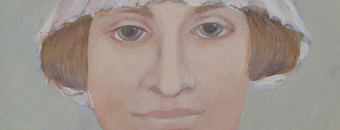

She is a portrait painter, taking portraits as her models. With the ‘Kotik collection’ painted by Gniazdowska, we find ourselves set face to face with portraits of various people once portrayed by Kotik as part of his collective photographic portraits. The painter satisfies the daydream of several: to meet those from old photographs; to make their cheeks flush; to see their badges and embroideries grew colourful. These pictures just can’t wait to get ‘coloured’. So that those people can be seen, all at a time. And this is what Gniazdowska attempts at getting done. And then, she carefully takes some of them out, and transfers them through time. No bonnet has ever fallen from anyone’s head, not to mention an officer’s hat. Some white dog has been drawn into our contemporary time. To me, Gniazdowska is a painter of ghosts. A realistic one, though. Combination impossible? Not really so.

War mothers the phenomenon so common during WW1, have been elicited out of ‘A Protectory, Belgrade’, a photograph by Kotik, to show the various statuses: lady bareheaded; lady ‘hatted’; lady ‘headstrapped’.

It is not so easy to paint time. Especially, after a multitude of other painters who made their attempts in the past. The past is only accessible to us as a puzzle of space and time, a shadow looming up, some hardly graspable outline. So little remains of it. But, on the other hand, one gets so surprised that so much remains, actually. There are no people of yore any more, but some documents remain. Empires and kingdoms have decayed, whilst some portraits or photographs are still with us. A plenty of them have no caption attached. Such photographs show people who were once close to someone, loved by someone, unknown predecessors of our neighbours, ourselves, perhaps, dwellers of some faraway lands.

The photo captioned The Switchboard seems extremely appealing and picturesque to us. The ancient-looking headphones of the monitoring crew tapping their mysterious telegrams transfer the viewer into the period of yore even more efficiently than the uniforms can do. The respective paintings are entitled Interception and Switchboard.

Group pictures so loved by our ancestors often have a shared caption, but we do not get to know the individual names this way. A crowd of figures, in sepia, in black and white, or rather, in grey and whitened grey, stare at us tensely. This is a glance of those who were forced to pose for a much longer time than we are accustomed to do; of those sensing that time has its own weight, a just one.

The war is on. It has come only naturally for the uniform-wearing boys from A Protectory, Belgrade picture to get to the world of adults, through the painting titled Conscription.

No portraits can ever be more serious than photographs from the Great War, nowadays referred to as the World War 1. Reinhard Enenkel has once offered Ms. Gniazdowska access to an excellent collection of pictures by a certain Kotik, the Czech war photographer, which he owned.

And, what can you pick out from the picture captioned Civil stretcher-bearers. The hospital, Belgrade? These are angels, as no-one would doubt. In Gniazdowska’s interpretation, one of those female volunteers gets transformed into a ‘Little Angel making you lucky’, the frame becoming a record of the depth of time.

Being a real painter of the 21st century, for whom time is apparently not clearly linear, she gave them some unexpected arch of time and placed there, in front of us. She ‘foretells the past’, as says of herself. So, she can probably see ghosts, like a decent clairvoyant? Yes, something of this sort. And, not only can she see them through the photographic medium; not only does she gaze at them, displayed on her computer monitor (since not quite long ago), taking advantage of the blessing of magnification (she would use a magnifying glass before), but also, she can paint them.

She portrays people entirely unknown to her, long ago deceased. She enters their grey world, and sometimes would remain there, in the grey. But now, she has transferred some of them into a colourful world, together with the period props. What kind of props? The clothes, namely. That was still a period of uniforms with numerous colour extras, various caps or hats, innumerable distinctions by way of shapes, colours, extras, badges, plumes, as well as women’s caps, headscarves, embroideries, hats: the long-lost alphabet of peoples, occupations, positions held in what was the Austrian-Hungarian empire.

Everyone you can see in those photographs is proudly convinced that his or her effigy will survive. It can be assumed with quite a probability that for many of them, this was the first photograph ever taken of them. Often, the last one, too. But none of them, and none of us indeed, could expect to see their painted portraits in 21st century. Gniazdowska’s vision has already become mass and democratic, in a sense. All of them made equal in their facelessness. She does not get impressed by the aristocratic name of an officer in the ‘9th corps’ photograph, reading ‘Graf Kinsky zu Wichinitz und Pettau’. Prince Józef Poniatowski was related to that family, through his mother; to a nineteenth-century painter, with the ‘history of the Kings’ as his educational basis, this fact would be of primary import. Gniazdowska is more interested in the faces and rank insignia – like in The boundary marker [Słup graniczny], or even, in a dog as a friend – like in Friends [Przyjaciele]. The first mentioned picture is very interesting: it is formed of eight portraits from the ‘9th Corps’ photographs, inscribed into the slanted black-and-yellow strips of the landmark. All this makes a very modern impression, despite the fact that the time of WW1 gets excellently reflected in it.

Bogna Gniazdowska’s paintings satisfy your daydreams desiring that historic memory, as well as a ‘straight’ memory, may not only persist but also reveal to ourselves in a physical manner. The beauty of those pictures is an extra gift.