From the beginning

From the beginning

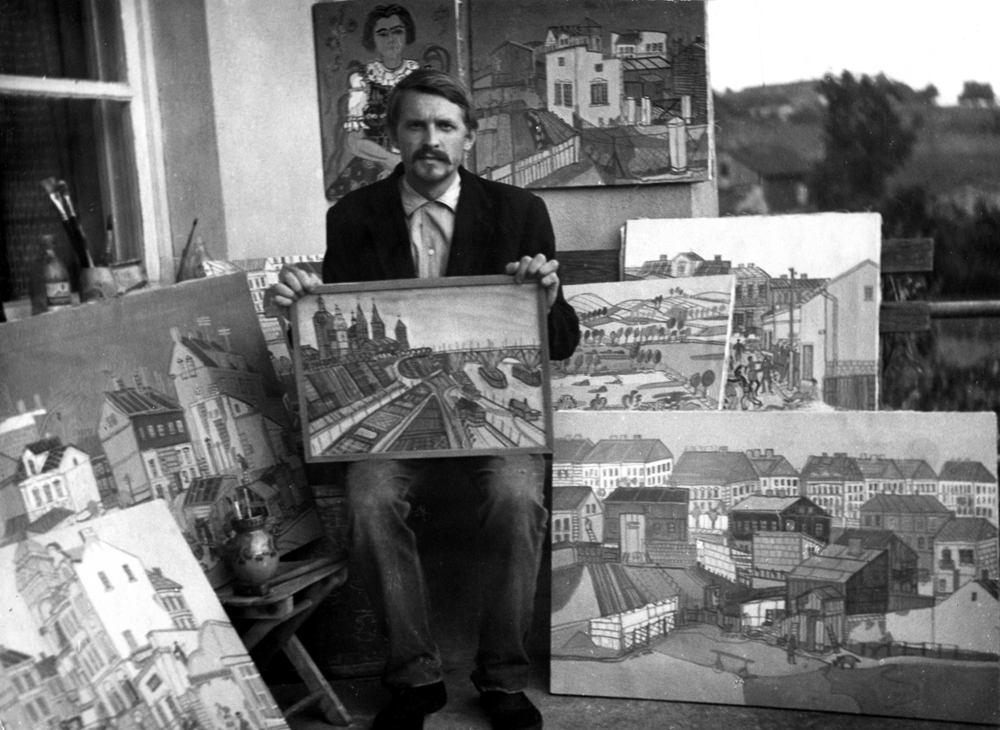

Edward Dwurnik is an indefatigable worker. His productivity is legendary. Art critics, exhibition curators and journalists alike all revel in giving the numbers of pictures he can create in a week, a month, a year.

When you reach two hundred paintings a year, no one even tries to count the works done on paper anymore. Only Dwurnik himself can know his whole output, as even those art dealers who are on the best of terms with him are seldom invited to the upstairs studio where he keeps his drawings.

I’ve got storerooms full of paintings at home, huge chests of drawers stuffed with drawings, and two studios where I’m always working on something new, he says. I like to be orderly and systematic though. My paintings are all inventoried and arranged accordingly in the storerooms. I keep works on paper in these Bulgarian-made metal chests of drawers. I first saw such chests in the Lenin Museum and I immediately coveted them. I finally managed to get some towards the end of the 1970, after I’d heard there was this place in Wola that was selling them. So off I went, and there was this tarted-up girl sitting behind a counter who said, ‘We’ve got lots of these drawers, but they’re all damaged. The Bulgarians didn’t package them well enough, and when the train braked they all came tumbling down and got dented.’ I went into the room where they were stored and chose the ones that were in best condition. I bought about ten of them. Then I put new wheels on all the drawers, because the old ones were all smashed and bent. Now there are thousands of drawings in those chests, but I always know where everything is.

The Bulgarian chests of drawers resemble Ali Baba’s cave in the Arabian Nights. Thousands of drawings, all excellent, surprising, delightful. The artist selected his works as he produced them, keeping only the best and burning the rest or putting them in the bin. As a student he repeatedly blocked up the chimney in his family home in Międzylesie with the soot from his burnt drawings.

I worked like crazy at the Academy, he recollects. In Professor Józef Pakulski’s lithography studio I made drawing after drawing after drawing; my head was overflowing with ideas, there was simply no way I could work through them all.

He talks about printmaking with nostalgia. In the bathroom by the upstairs studio there are still lithography stones lying about. Dwurnik says he’d like to go back to lithography.

But for now a pencil or a pen are enough. As for ballpoint or felt-tip pens, he discovered how impermanent they are years ago, when his drawings started fading away, disappearing. They needed conservation.

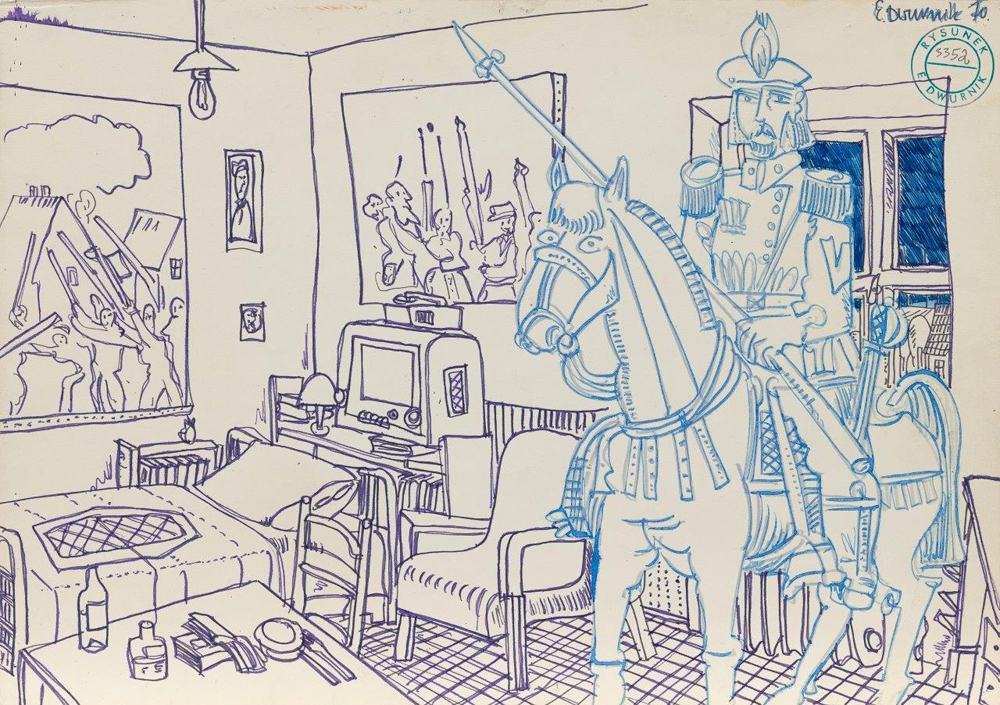

Those drawers are a chronicle of Edward Dwurnik’s life: scenes from his family home, from student parties, from the studios at the Academy of Fine Arts, from his famous hitchhiking trips, when he travelled the length and breadth of Poland with a sketchpad under his arm and a pencil in his pocket, and from the trip to Paris in his youth. Add to all this scenes observed between the bus stop and the Academy, as well as those inspired by history, literature, art, politics, and everyday life. His drawing of A Painter’s Vision shows the sort of things that can go on inside an artist’s head: a studio with everyday furniture, its walls covered in paintings, and a cavalry officer riding into it on horseback, lance in hand.

Dwurnik’s creative urge is so powerful that he produces an enormous quantity of work with no compromise on quality. What in the end is the point of counting the pictures? It’s not numbers that captivate us, but true art.

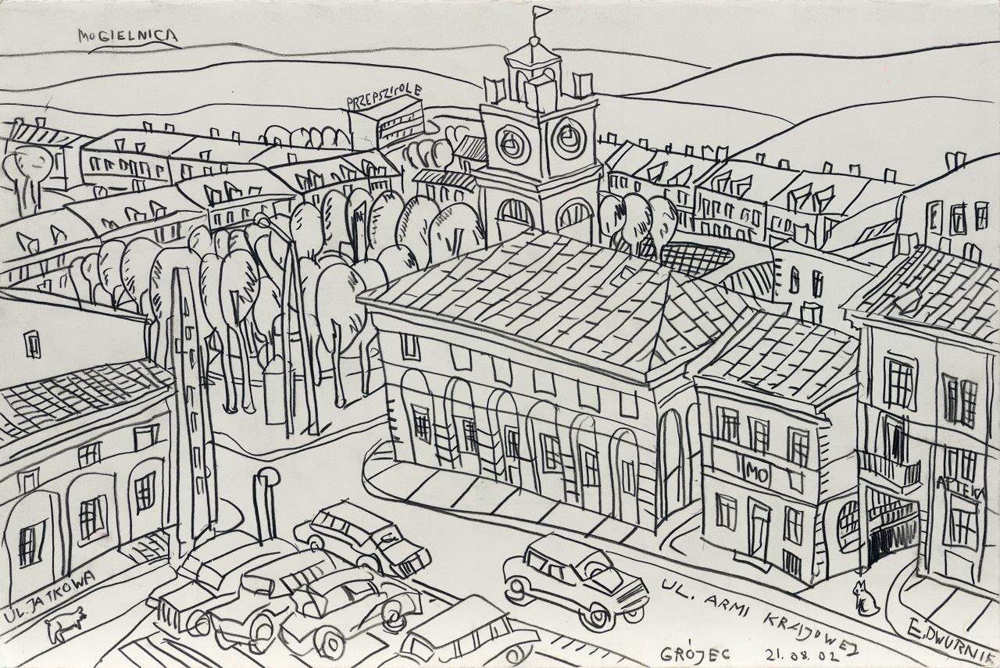

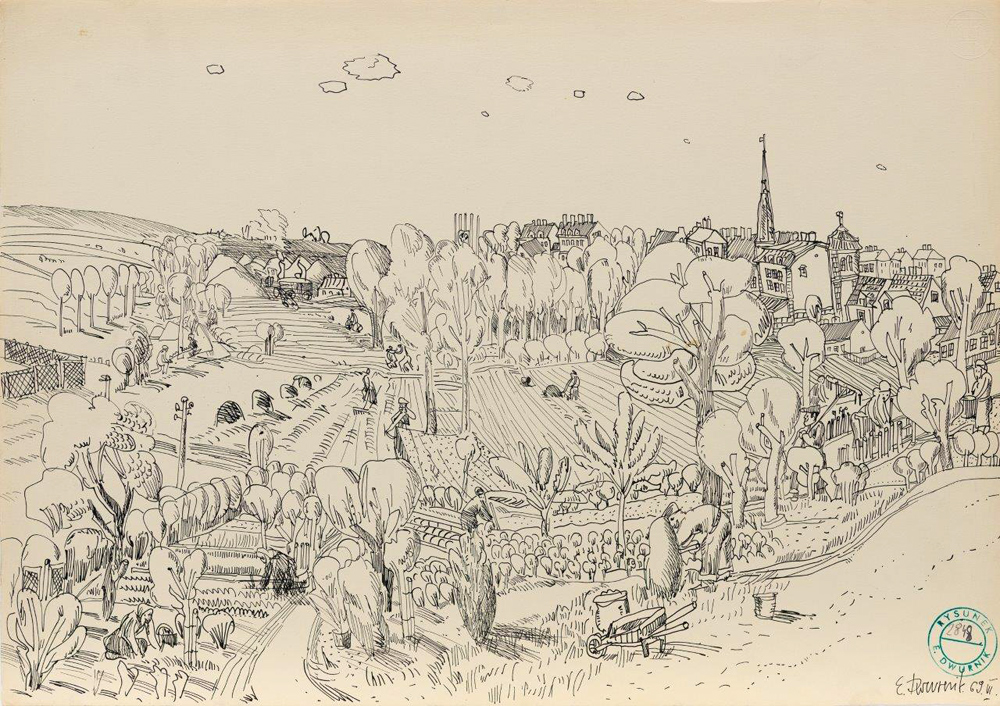

Grójec

I made this drawing from memory. It’s Grójec as it is inside my head, in my memories. You could say everything began there, even if I was born in Radzymin. But it was in Grójec that I started (…)

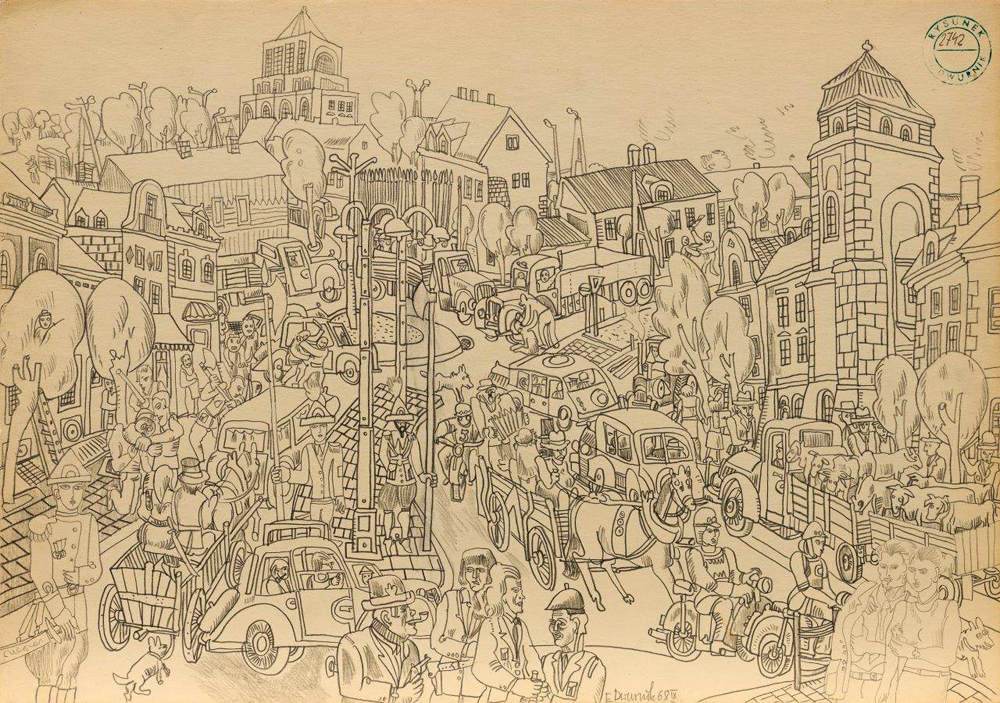

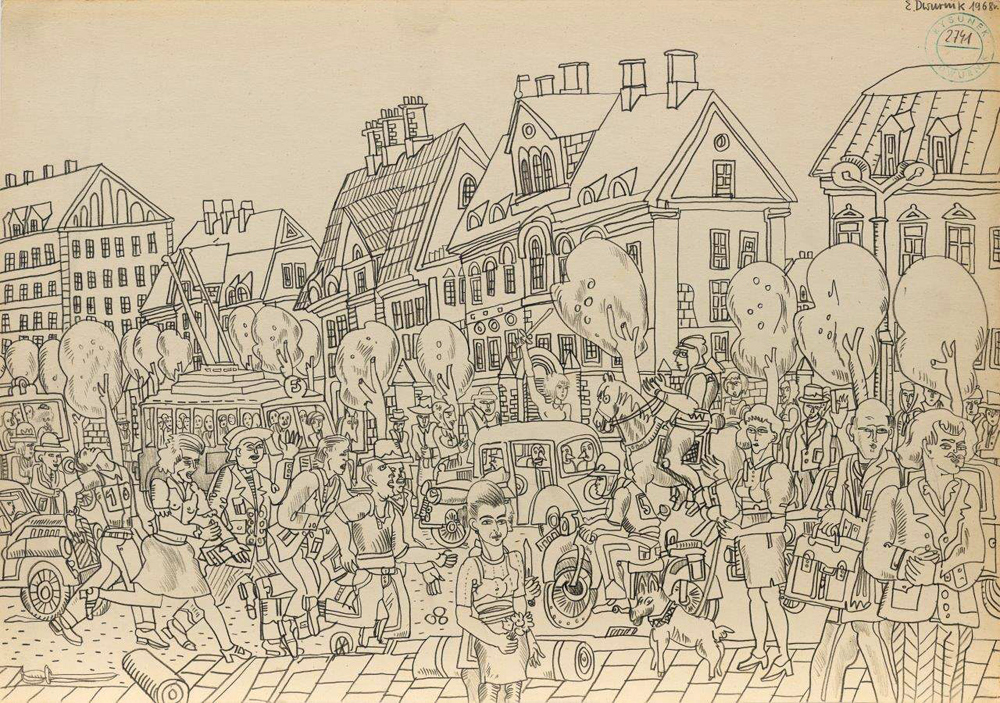

I made this drawing from memory. It’s Grójec as it is inside my head, in my memories. You could say everything began there, even if I was born in Radzymin.

But it was in Grójec that I started drawing. I was a sickly child, so I spent a lot of time with my nose glued to the glass of the window. Today a sick kid will sit with his nose in a tablet, but in those days you looked out of the window for entertainment. We lived in the main street, in the heart of town. Opposite our house there was a pharmacy, a greengrocer’s, the police station, where my father was chief officer, and the fire station wasn’t far off. I looked at the signs and I copied the letters precisely on a piece of paper. My parents and my granddad were delighted that I’d learned to write so early, all on my own. They thought they had a little genius in the family. But actually I couldn’t write - I could only draw. The kindergarten teachers were quick to spot my talents, though. Whenever there was an inspection, they’d rush over to the younger group, say ‘come on, Edzio’ and then take me into the oldest group where I played the role of the child prodigy with my pretty pictures. Obviously, the older children were pretty pissed off with me.

But Lordy, what stuff I saw from that window! There were scenes that would be hard to credit nowadays, but I keep going back to that resource, that kaleidoscope of events, images, memories. I saw policemen taking prisoners to jail and firemen pelting off on a call. A couple of times a week the sirens would wail and the firemen would screech away to a fire. And what wonderful cars they had! One was green, German, left over from the occupation. Their sirens were great things too, none of your modern electric rubbish. One fireman would sit astride a bumper, close to the huge flashing light, holding on with his legs, and he would set the siren wailing, cranking it by hand.

Or the market! There was a market behind our house every week; carts would come with goods to sell. Jezu, there was so much going on there! One winter my mother and sister were pulling me behind them on a sledge when they suddenly started laughing and saying Edzio, don’t look, close your eyes! So of course I looked, and there’s this man pulling a cow on a halter; his trousers have fallen down, because the string that holds them has come untied, and underneath there’s just this big bare white bum. Everybody laughed like hell.

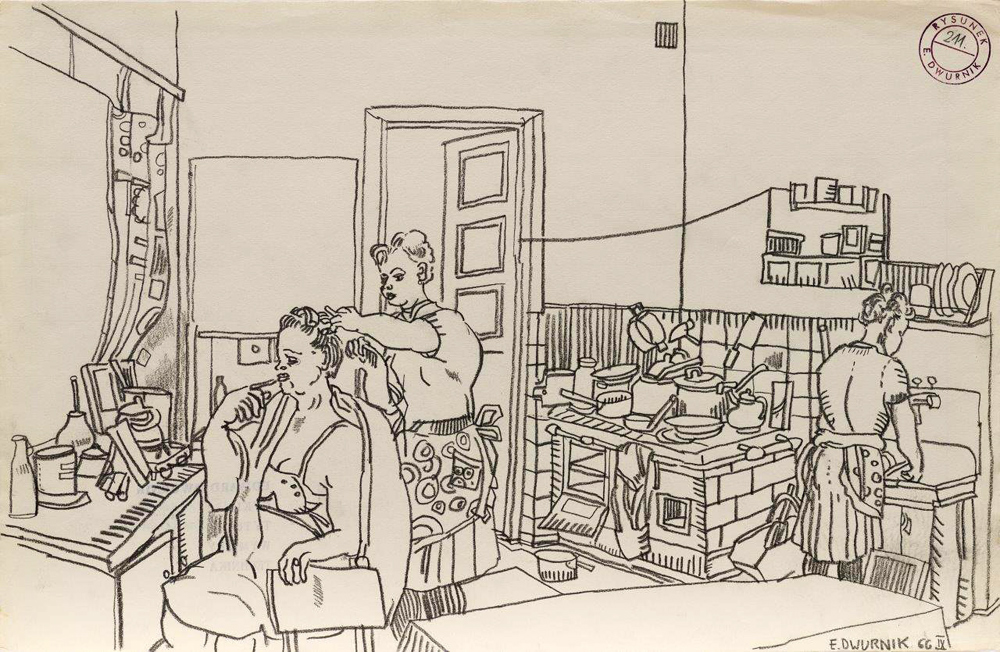

The kitchen

In every house where I’ve lived the kitchen was the most important room. That was where life really happened: kitchen life and social life. The cooking, the washing, the talking; my mother, sisters (…)

In every house where I’ve lived the kitchen was the most important room. That was where life really happened: kitchen life and social life. The cooking, the washing, the talking; my mother, sisters and aunts even permed their hair there. I don’t remember if we ever found a hair in a bowl of broth, but it could have happened. My mother always used her own chicken to make broth. She’d grown up in the countryside and was used to the idea that there must be chickens in the yard, and that you should always have fresh eggs. In any case, times were such that it was good to have your own eggs. My brother-in-law used to get really pissed off though; he said he was sick of forever stepping in hen shit.

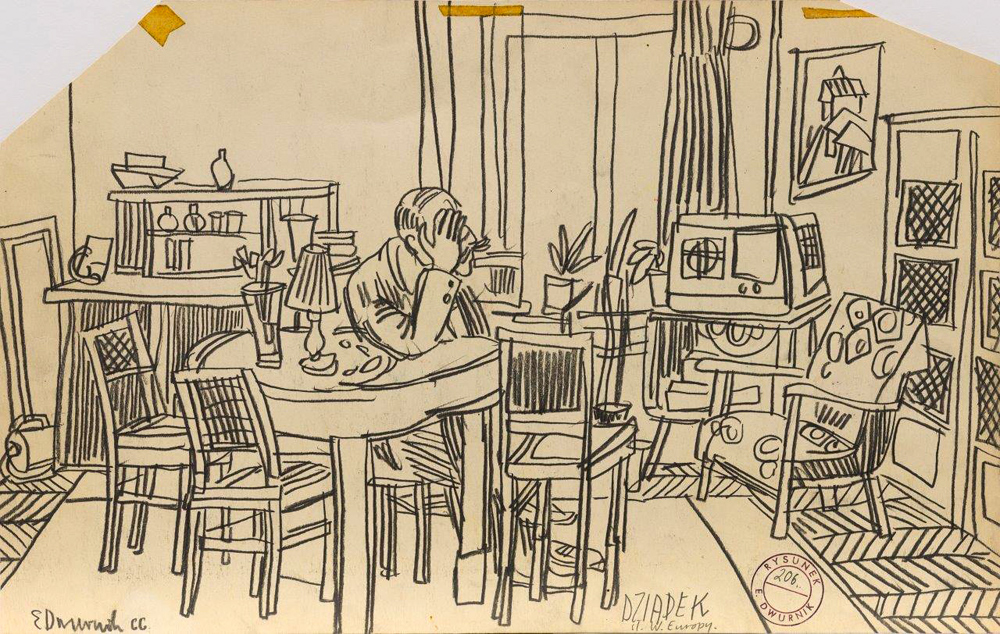

Granddad

My grandfather Władysław Dwurnik is sitting with his elbow on the table, one hand propping up his head. You can see his cool moustache and the neat parting in his hair. But you can’t see his dark (…)

My grandfather Władysław Dwurnik is sitting with his elbow on the table, one hand propping up his head. You can see his cool moustache and the neat parting in his hair. But you can’t see his dark eyes. My father was also named Władysław, and my mother, Władysława. But she was so embarrassed about being ‘Władzia who’d married Władzio’ that for a long time my siblings and I believed her name was Anna, because that was how she always introduced herself. Granddad had been with our family ever since I remembered; he practically replaced my father, who worked in the so-called forces. So it was really Granddad who brought me up, who told me to say grace before every meal and so on. In the evening I had to kneel in front of a crucifix and say my prayers. Granddad lived with us in Mława, then in Grójec, where he made soap from dog fat in the yard behind the house. The fat was delivered to him in buckets by the dog-catchers. Granddad had this huge can, an enormous vessel it was. He would place it on bricks and make a fire that he fed with wood gathered in the forest by other men. The fat would boil, and the only place where you could do it was out in the yard, next to the privy that was shared by the whole neighbourhood.

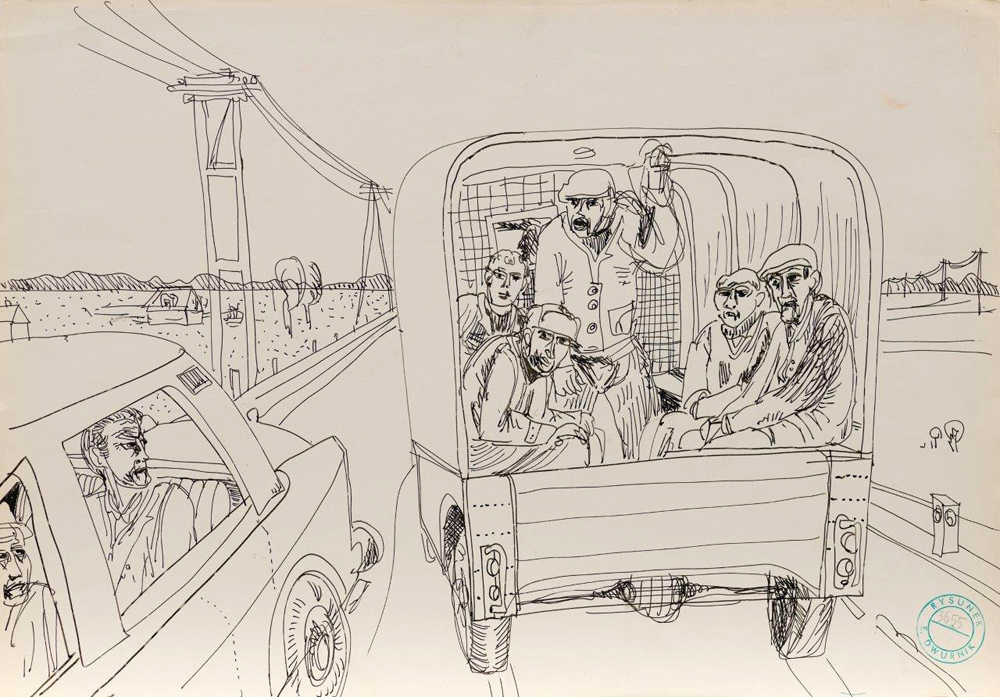

Good cars

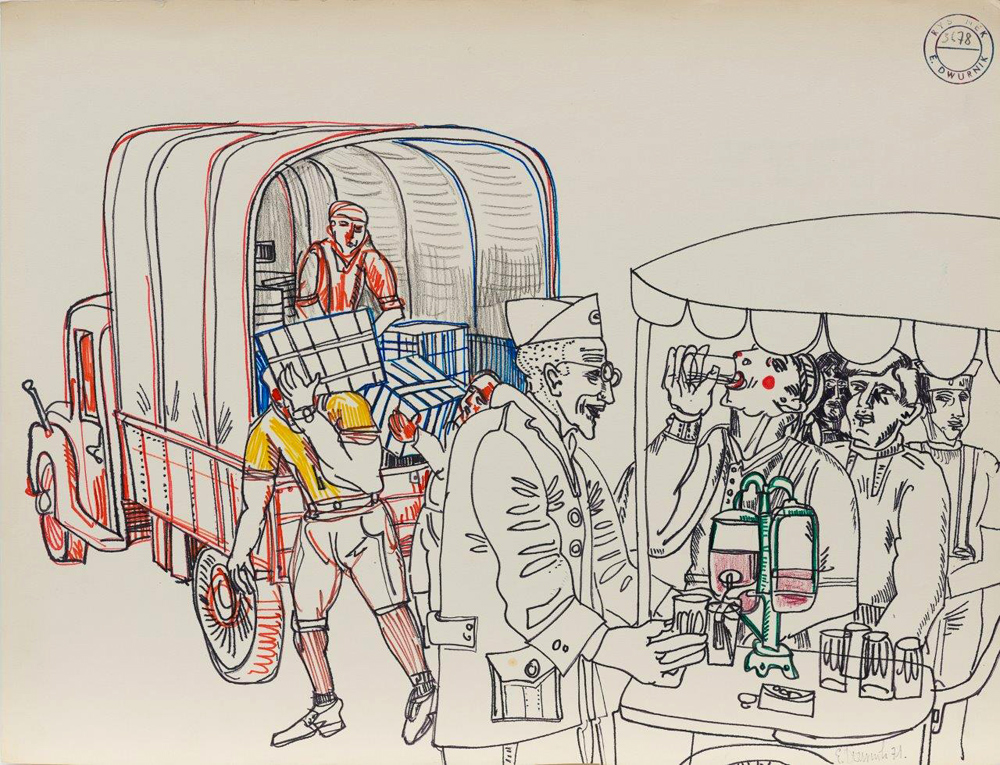

This is Poland! The envious looks of the workers travelling in the back of the lorry say it all. Social divide in a nutshell. A smart passenger car is what everyone wants. I’ve always liked good (…)

This is Poland! The envious looks of the workers travelling in the back of the lorry say it all. Social divide in a nutshell. A smart passenger car is what everyone wants. I’ve always liked good cars. I bought my first one, a Beetle, in 1976. As a young man I often acted as chauffeur for my father. He used to buy Warszawas; he had three of them one after the other. The first was second-hand, and the other two were new. He didn’t want to drive himself. He said it made no sense, as it meant he couldn’t even have a drink. Sometimes he wanted to go to Żoliborz. He had a mistress there. I saw her once, a good-looking woman. I drove him to her place maybe three times. He would say: ‘Wait a moment, I’ll be right back.’ And then it’d be four fucking hours, so I used to move to the back seat and go to sleep.

Down-to-earth realist

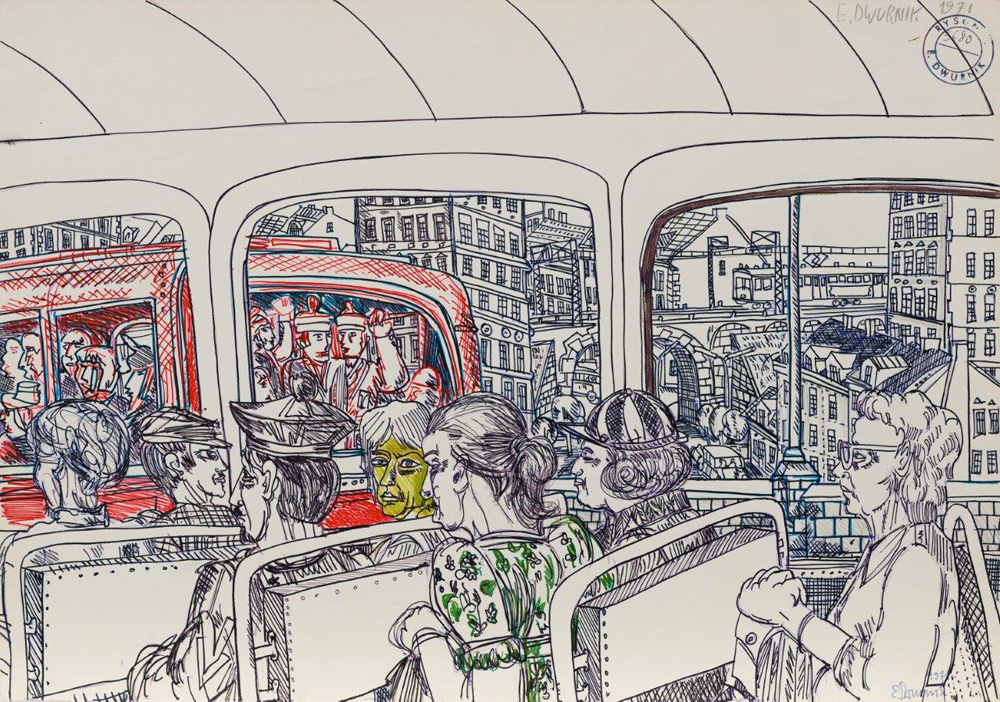

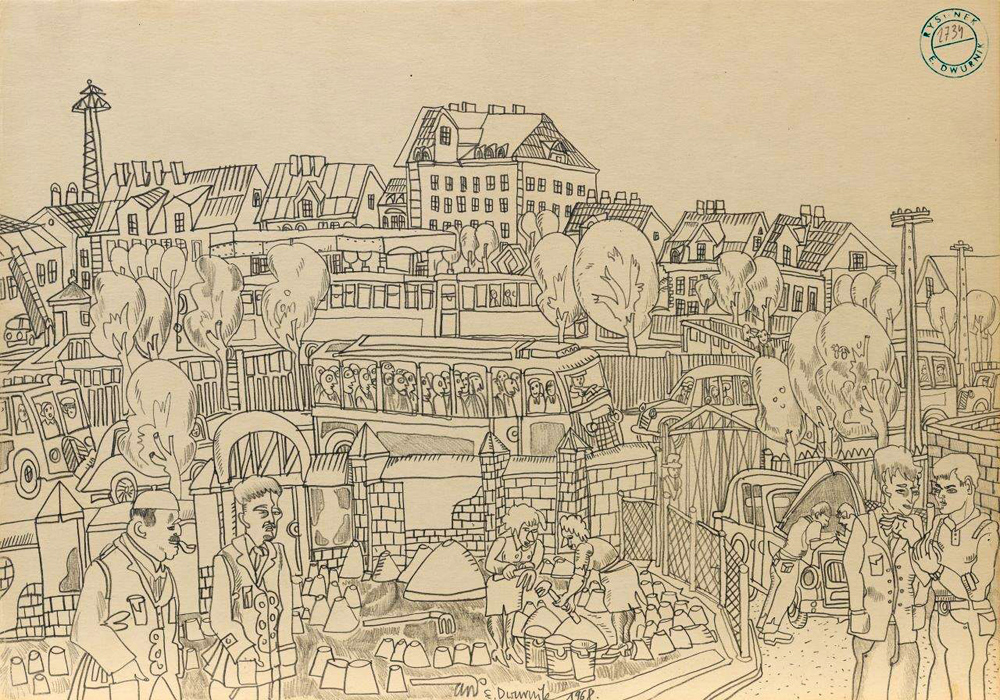

For years I used to commute between Międzylesie and Warsaw on buses and trains. The faces I saw, the reek of tobacco and alcohol I breathed, the oaths I heard... It all charged my batteries. In (…)

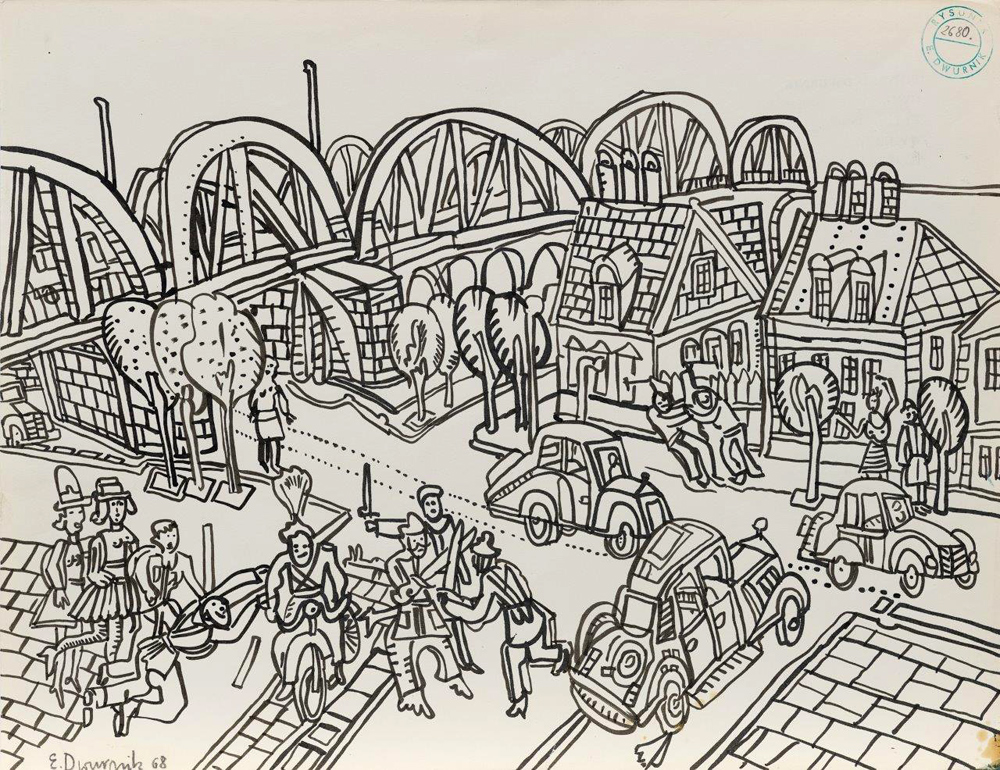

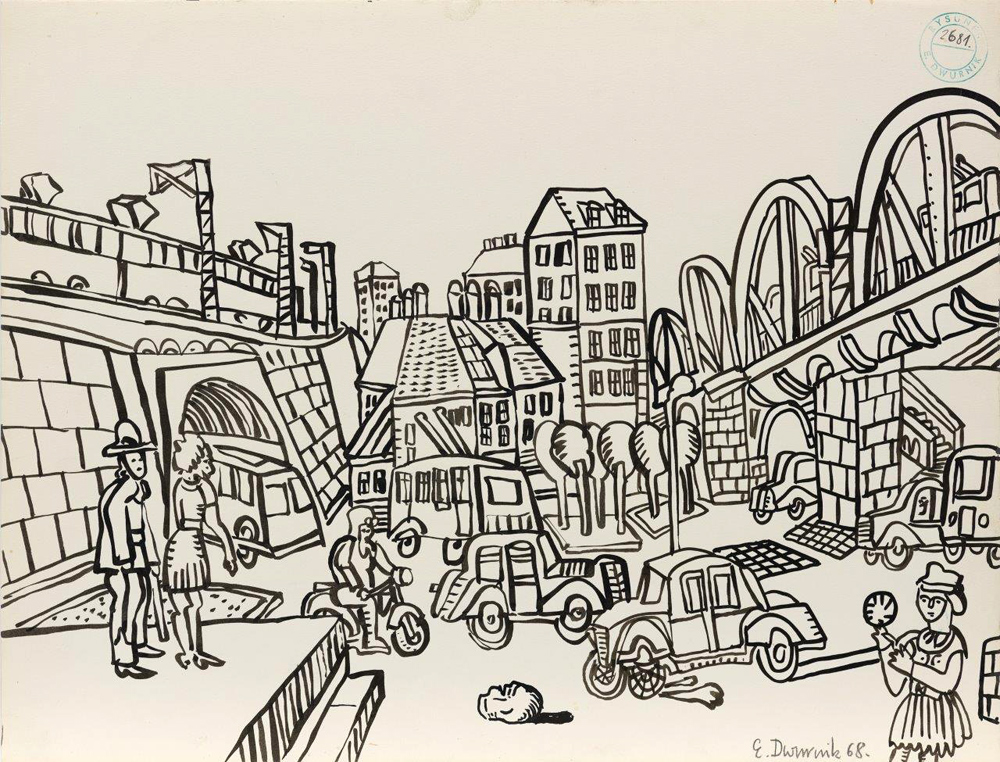

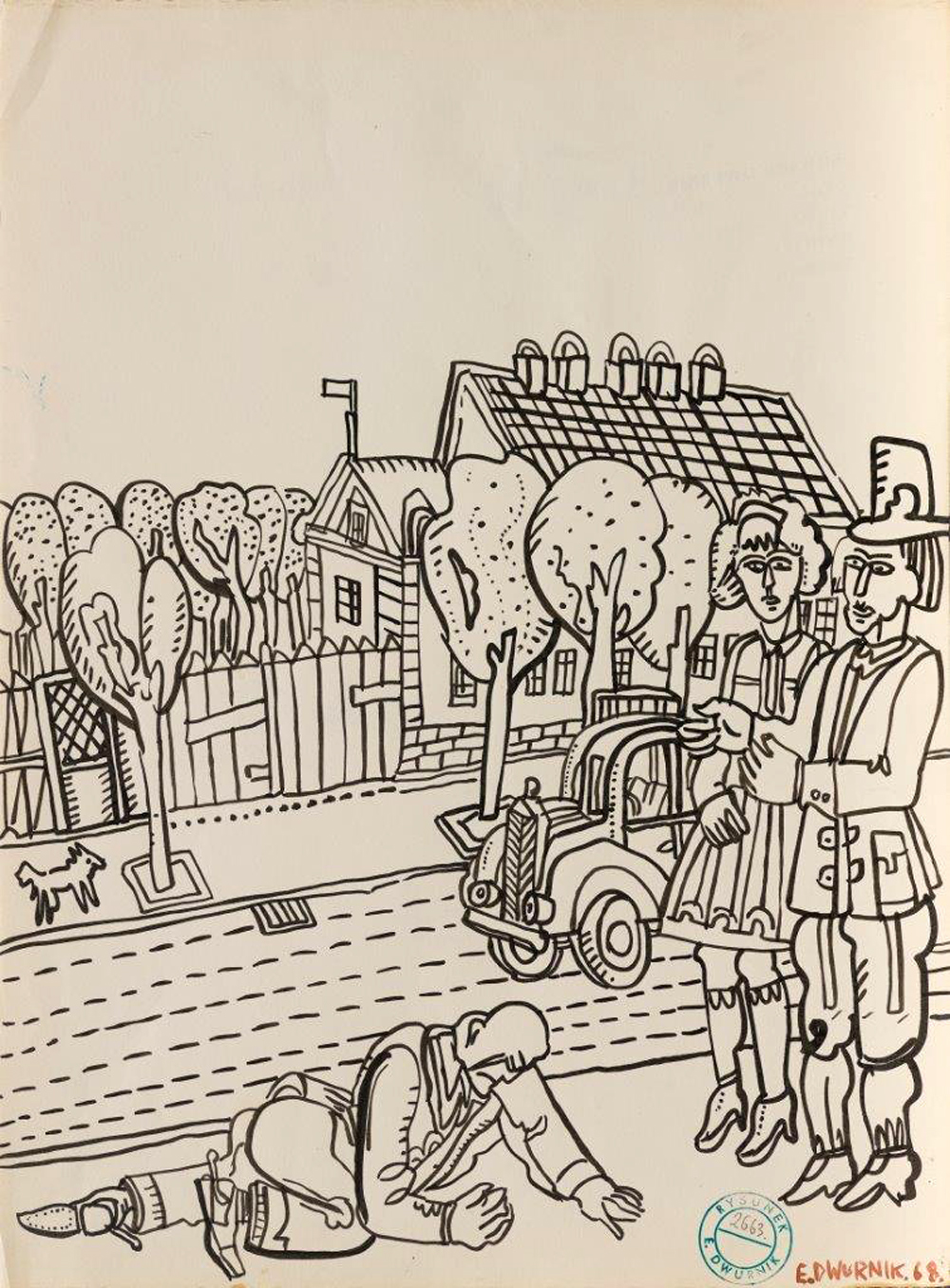

For years I used to commute between Międzylesie and Warsaw on buses and trains. The faces I saw, the reek of tobacco and alcohol I breathed, the oaths I heard... It all charged my batteries. In 1968, when applying for a scholarship, I wrote in my application: ‘I live in Międzylesie; it takes me an hour to get to the Academy; I encounter people on their way to work. I travel around small towns. I’m interested in average Poles; but I don’t consider them average, because they brought me up, and I believe I know their lives, their clothes, customs, beliefs, language – I love them, and it is a joy for me to build them a monument through my painting. They will soon be gone, as our country is undergoing great cultural and social changes. Soon there will be no distinctive railway station life, no provincial and small-town life, no third-rate restaurants and cafés, no second-rate men, women and girls. And there will then be no one who knows about all those things either; nobody will be studying them. […] I am not creating a legend, I am an objective, down-to-earth realist. Many people will recognise themselves in my paintings, where they are working, resting, playing or brawling.’.

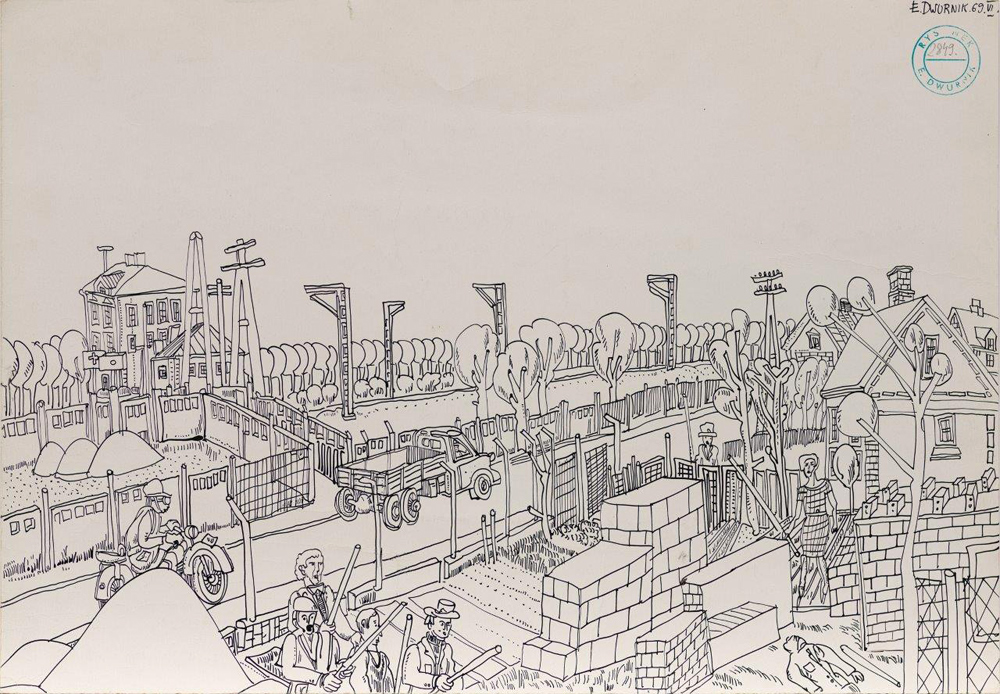

On a bender, or travelling in the footsteps of Nikifor

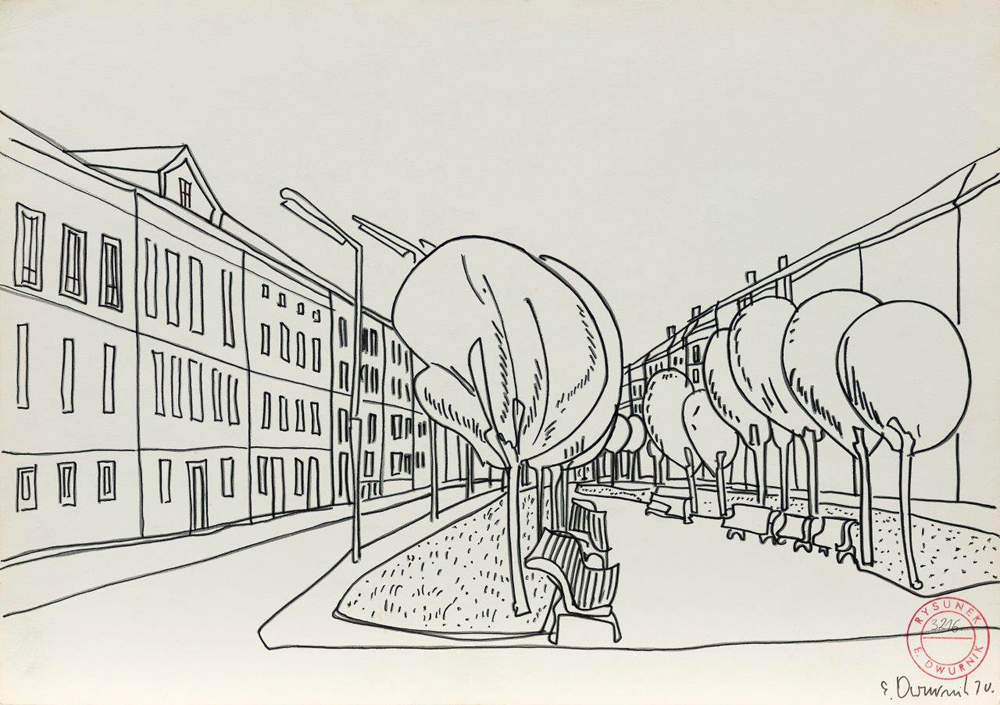

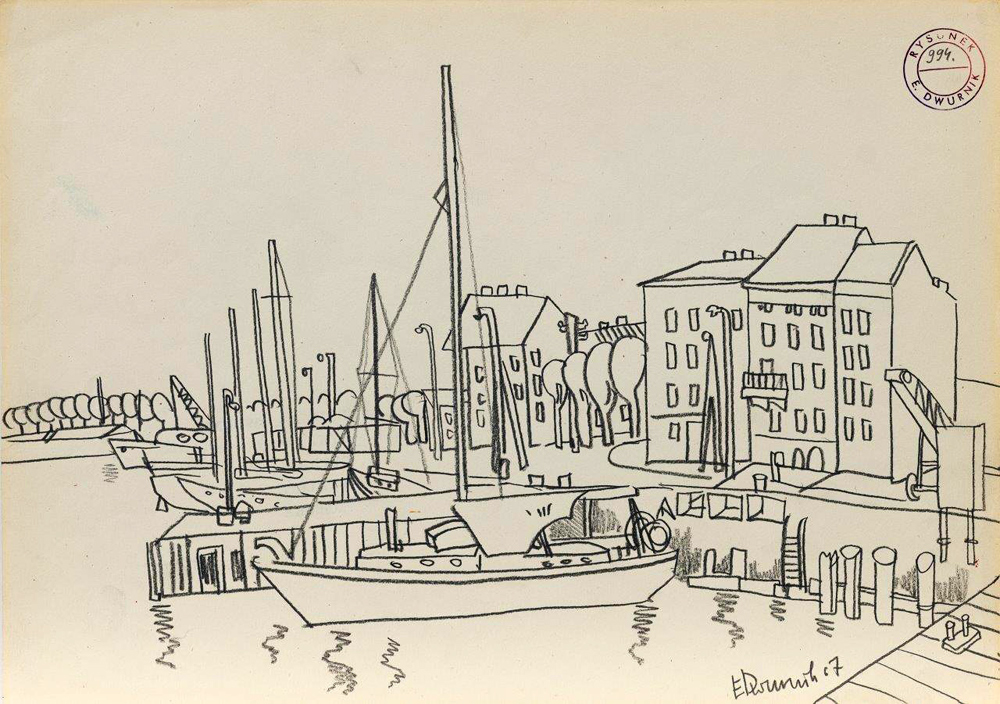

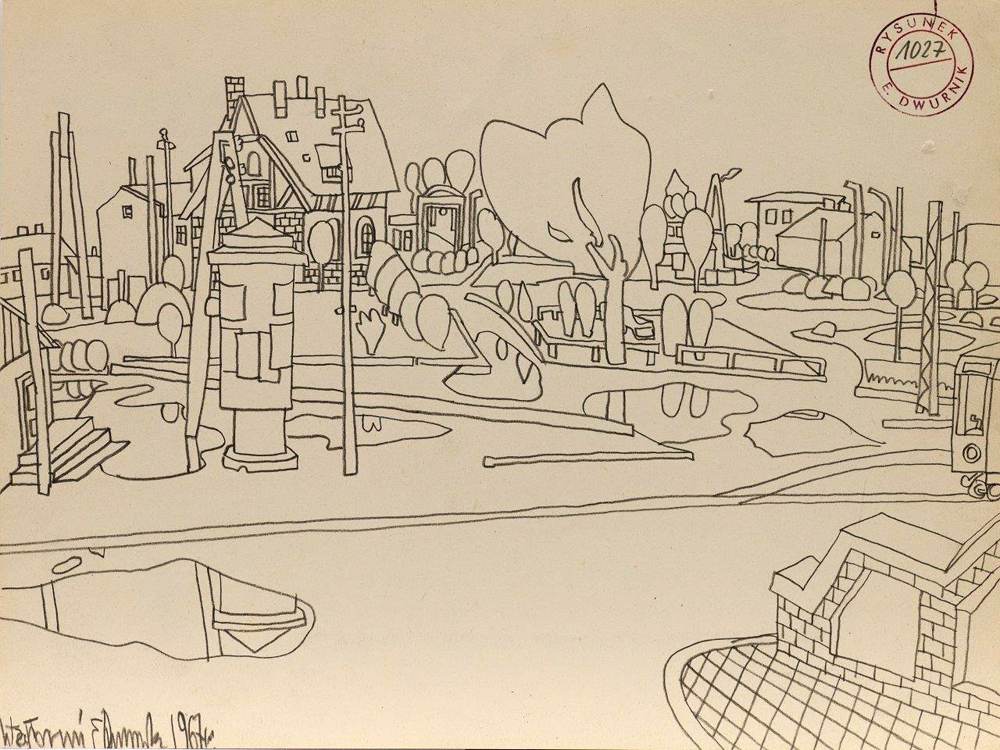

As a young man I spent a lot of time drawing outdoors. I drew so many corners of Poland, that if I were to name all the cities and towns, the list would be like the index of a road atlas. Hitchhiking (…)

As a young man I spent a lot of time drawing outdoors. I drew so many corners of Poland, that if I were to name all the cities and towns, the list would be like the index of a road atlas. Hitchhiking is my most popular cycle. It all started of course with my fascination with Nikifor. In the summer of 1965 I was at a plein-air workshop for students in Chęciny, and one day my mates and I went on a day trip to Kielce, which was close by. And there, at the International Press and Book Club in the main square, was a solo exhibition of Nikifor’s work. I knew his pictures from the reproductions that had appeared in the magazine Przekrój, but it was in Kielce that I first saw them live. My mates laughed at me, they reckoned I’d fallen to my knees. And it was true, I was absolutely dazzled by his imagination and talent; it was Nikifor who showed me the way. I wanted to paint architecture and landscape like he did; I borrowed his perspective and various other tricks. I travelled all over Poland with a sketchpad. I made a Nikifor-style journey from my home town, Międzylesie near Warsaw, to Międzylesie in Lower Silesia. My father and I agreed he would send me five hundred złoty a week poste restante. I would go to the post office and collect my allowance. Of course I had a much easier life than Nikifor: I stayed comfortably in hotels, while he had slept wherever, and often footed it instead of taking a coach or a train. He painted along the way, of course. And so did I, it was like an addiction, I was really on a bender. I would arrive in a town, get off the bus, sit down on the pavement and start drawing right away.

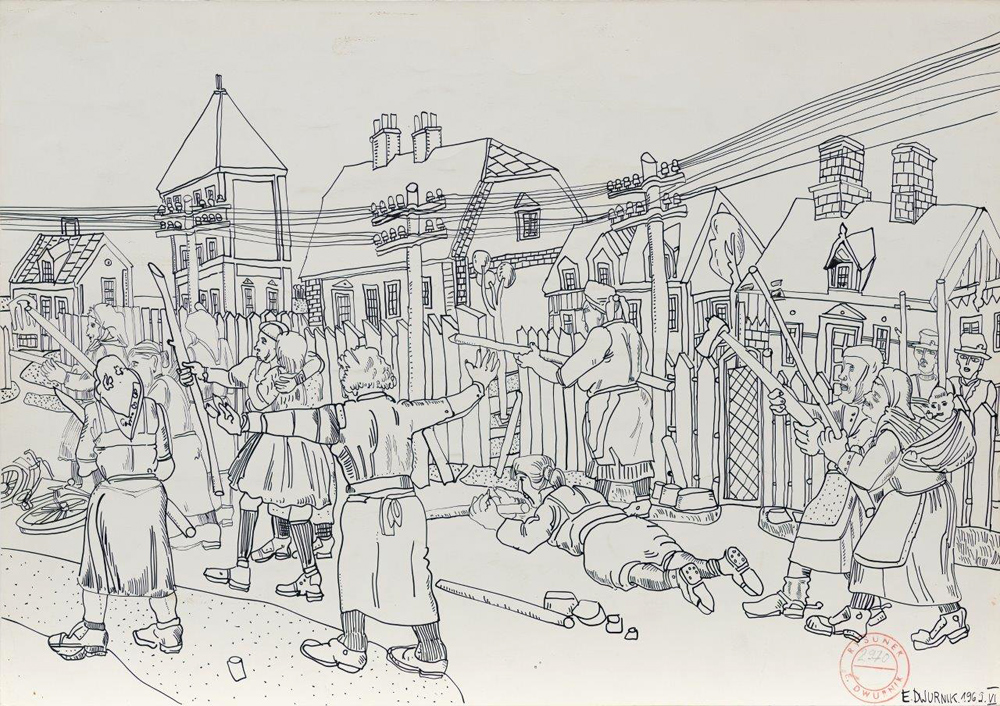

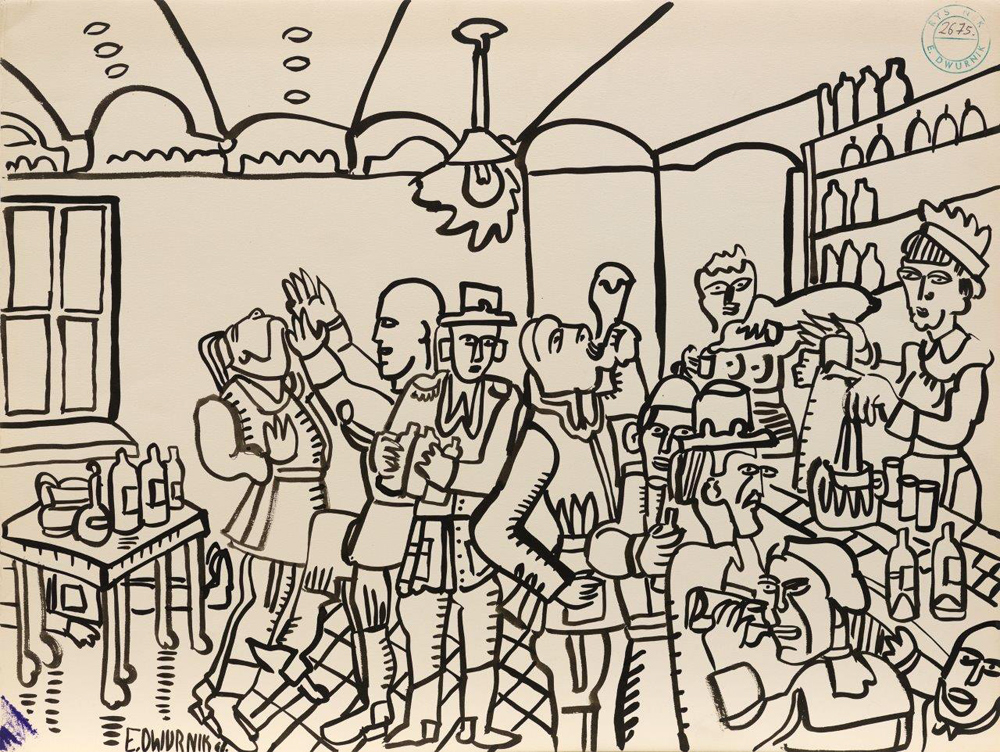

Brawls

I like the atmosphere of a brawl. As a boy and young man I was a bit of a hooligan, I was forever getting into fights with my mates. I even did it when I was already a student at the Academy. I was (…)

I like the atmosphere of a brawl. As a boy and young man I was a bit of a hooligan, I was forever getting into fights with my mates. I even did it when I was already a student at the Academy. I was constantly walking around with bruises or with a cut lip. One day, seeing my black eye, the father of my friend Ela (on whom I was sweet) told me that instead of getting into pointless fights I could do boxing, and that there was a boxing club by the Dom Słowa Polskiego printers’ in Wola. I was in secondary art school at the time and I decided to drop into that club and see how I liked it. Well, I dropped in and stayed for two years. It turned out that I had a good aim. You don’t have to hit particularly hard; you have to hit the right spot. I still watch boxing on television, and I still like it. I have put that inclination toward fighting into my painting. I kept on drawing and painting brawls. Movement is one of the secrets of art. Boxing and bodybuilding exercises have helped me capture that moment when the inimitable spirit of the hero who has authentic life in him is revealed. Because I knew how to flex a bicep or how to move without falling and making a fool of myself, I also knew how to transfer the impression of movement onto paper. Then I would add some attributes from a completely different context – I’d put a tight belt around a guy’s waist, or give him spurs, tall boots, riding breeches, sunglasses. Most often I’d draw street fights; I’ve got several drawers full of pictures in which the characters are hammering at each other with their fists, with sticks, with every kind of weapon.

Accidents

The head lying in the middle of the road is from an accident victim. The guy was probably hit by a train, and the head rolled off the viaduct. Accidents on the railway were an everyday occurrence. (…)

The head lying in the middle of the road is from an accident victim. The guy was probably hit by a train, and the head rolled off the viaduct. Accidents on the railway were an everyday occurrence. You heard of tragic deaths, or even saw them, all the time. Once, when I was walking to the Academy, I saw a bus hit a pedestrian. A crowd gathered, people screamed. But there was nothing anyone could do; I walked on to the studio.

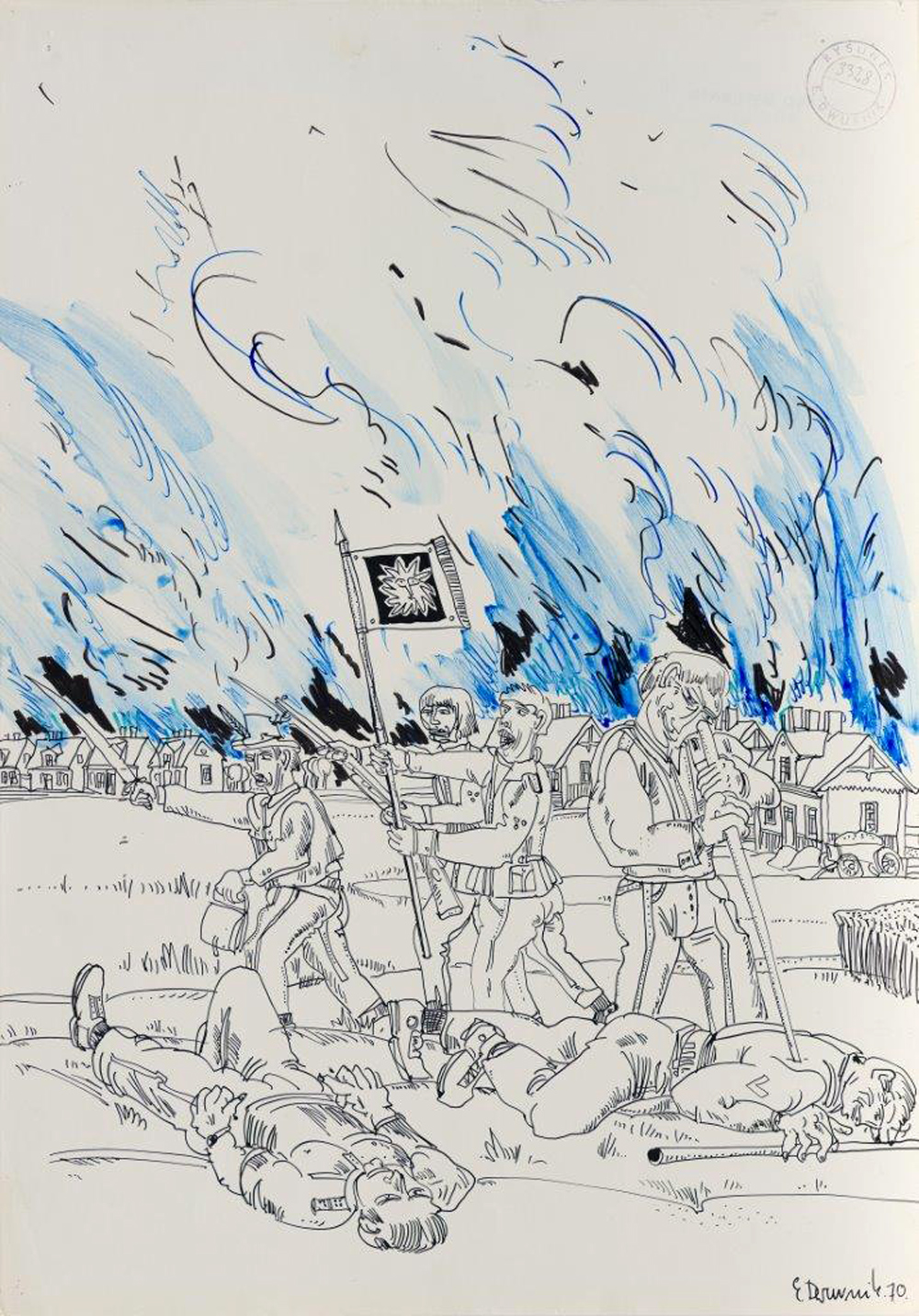

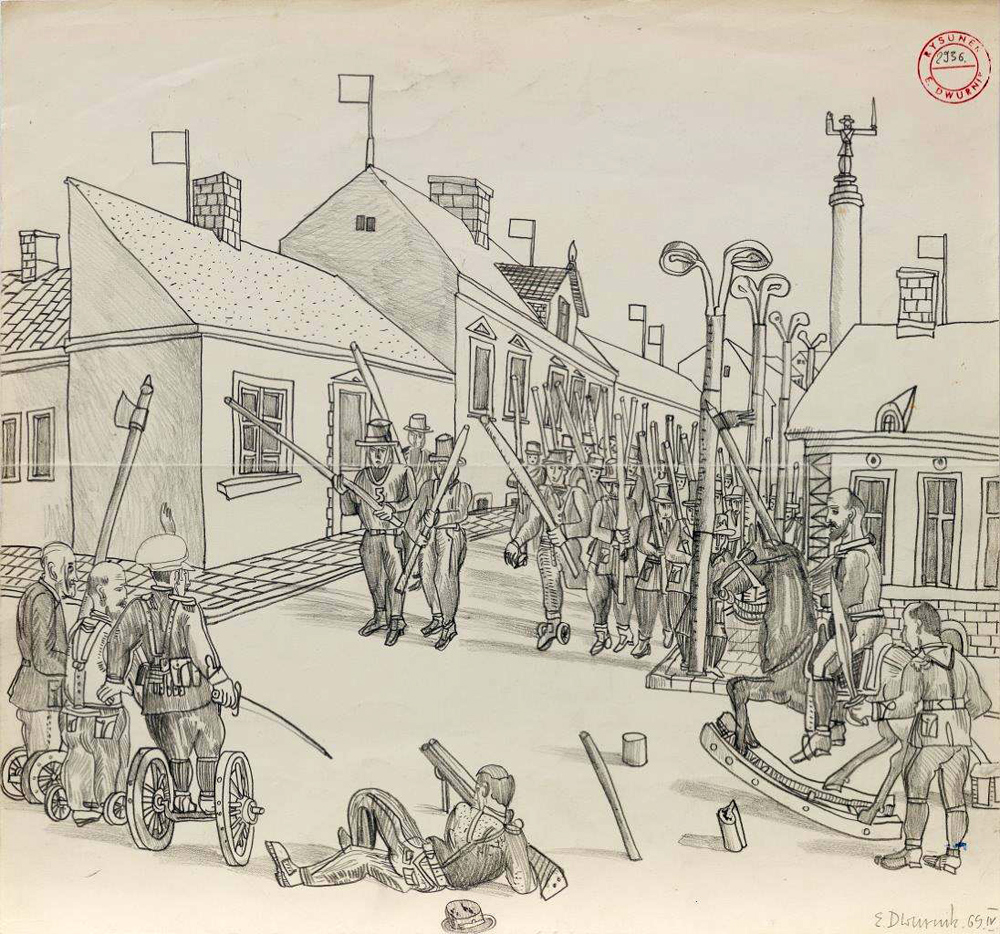

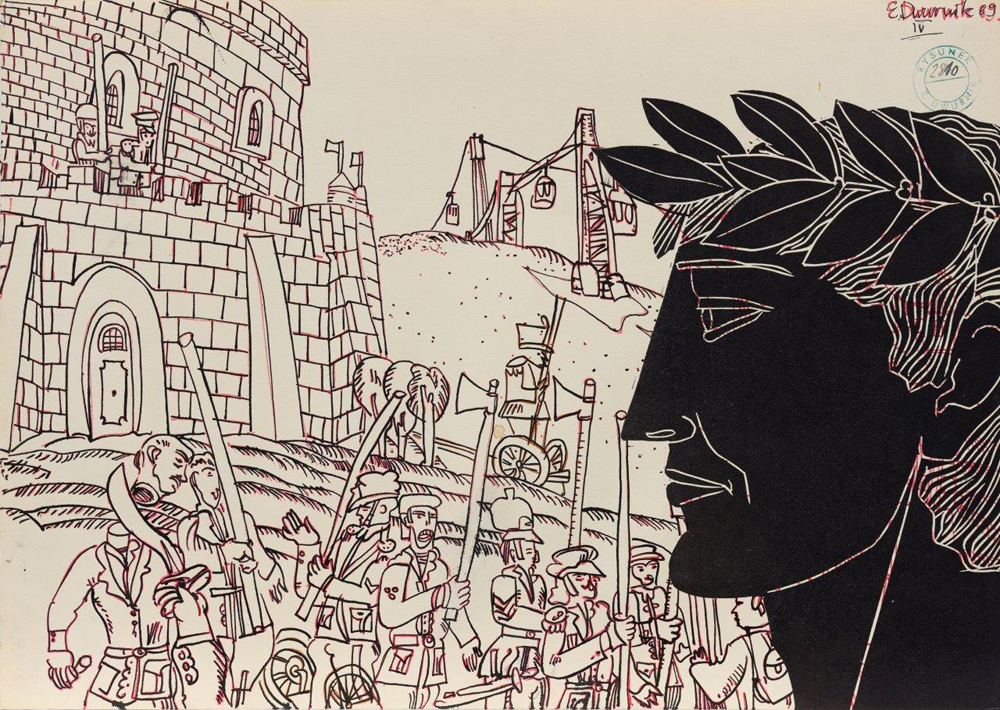

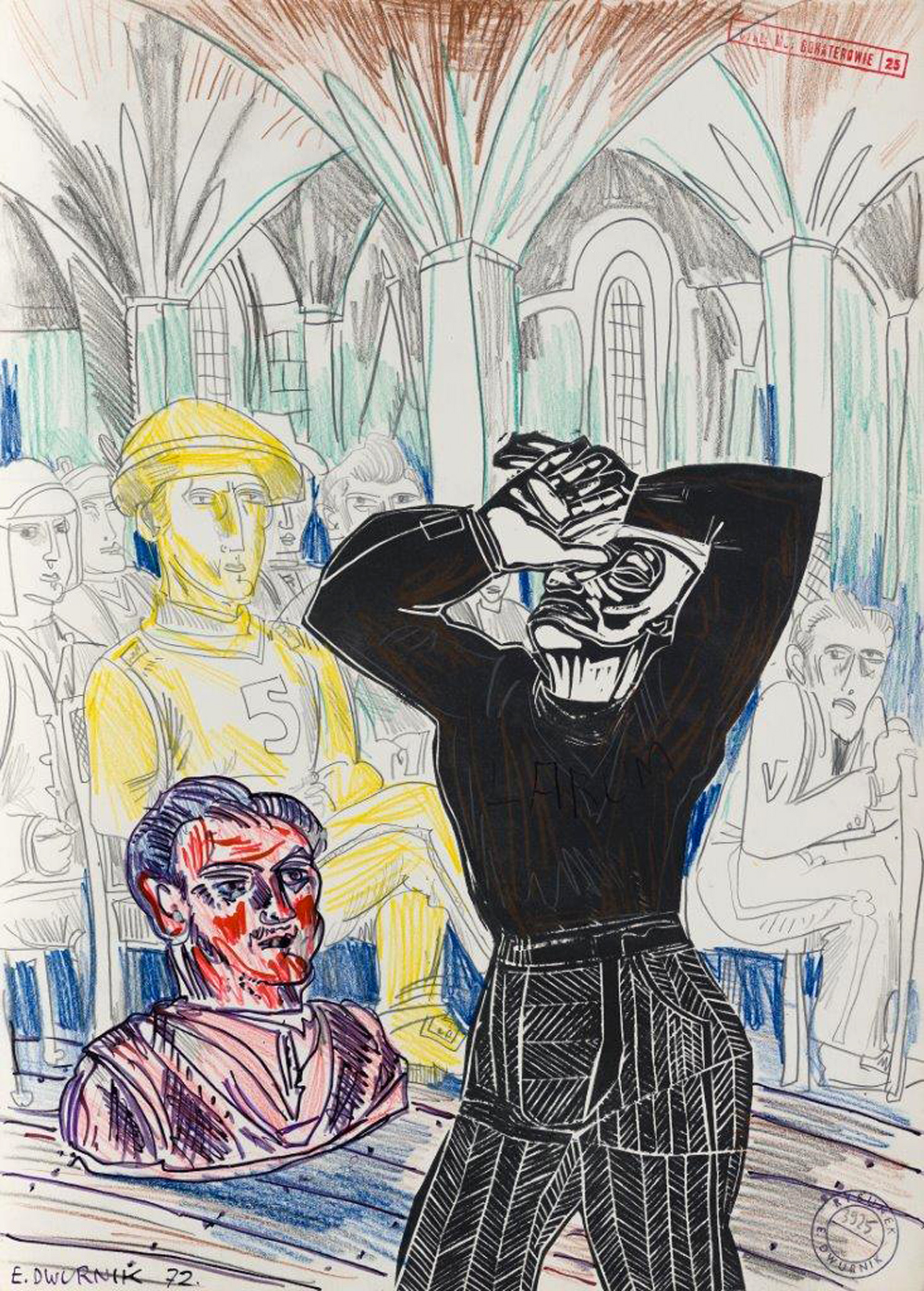

Armies and battles

A painter’s dream, a painter’s vision. If I were to lapse into metaphor, I could say that countless armies, historic figures, kings, poets, politicians have all passed through my studio, or (…)

A painter’s dream, a painter’s vision. If I were to lapse into metaphor, I could say that countless armies, historic figures, kings, poets, politicians have all passed through my studio, or rather through my head. I’ve always liked the narrative quality of Matejko’s art. I too like telling stories on canvas or paper. As far back as primary school I used to cover huge sheets of paperboard with battles – The Battle of Oliwa, Psie Pole, The Battle of Grunwald and many others. There’s a lot of narrative in my beloved Nikifor’s work as well. He would divide a plane into sections and create something like a cartoon: he told stories that might feature a priest, other people, interiors, extreme unction and so on.

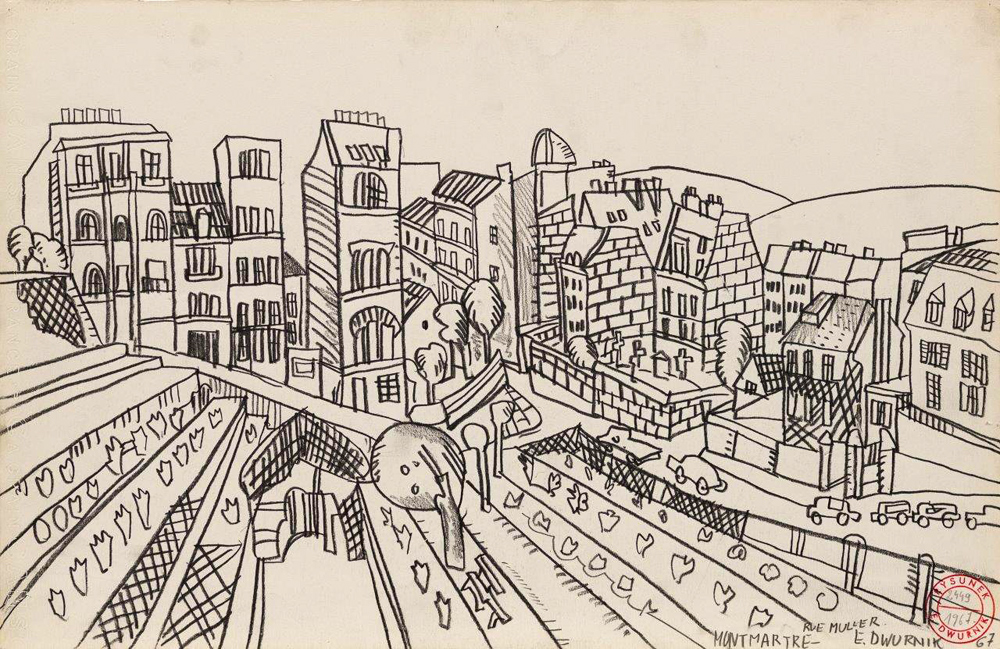

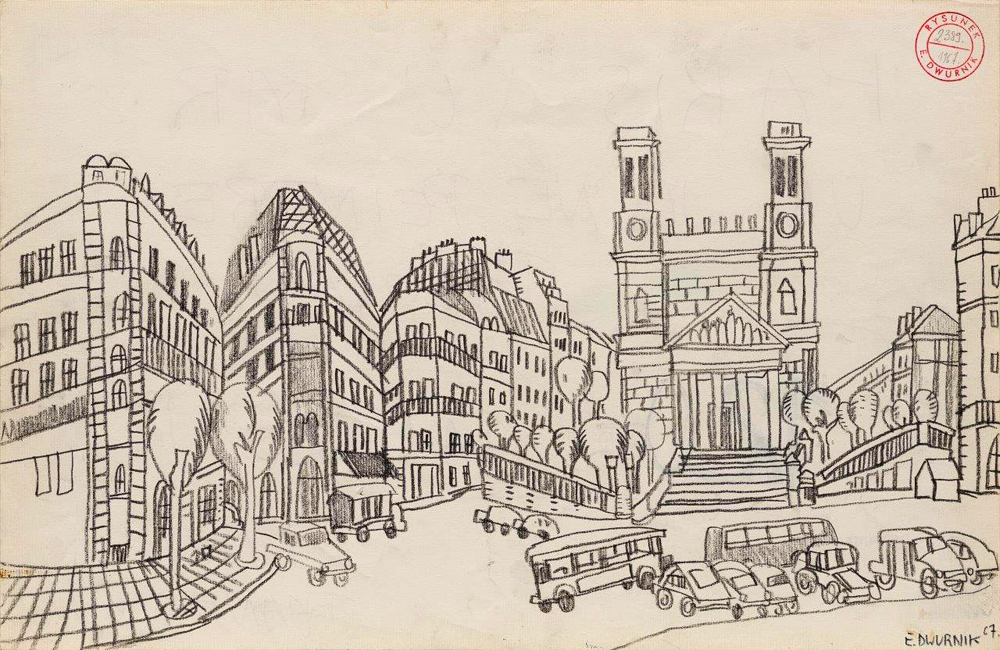

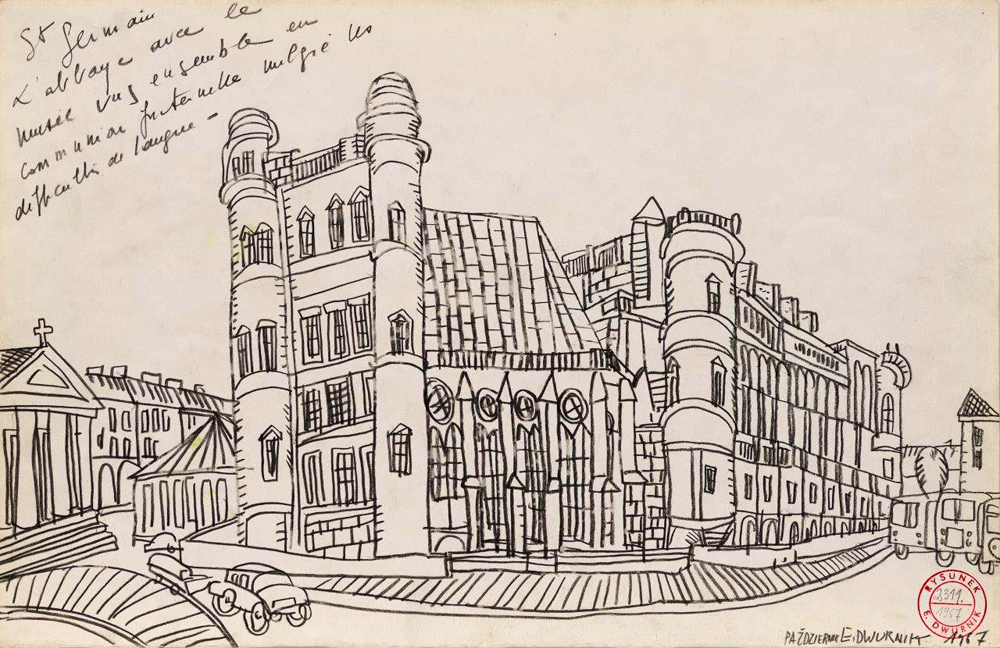

Paris

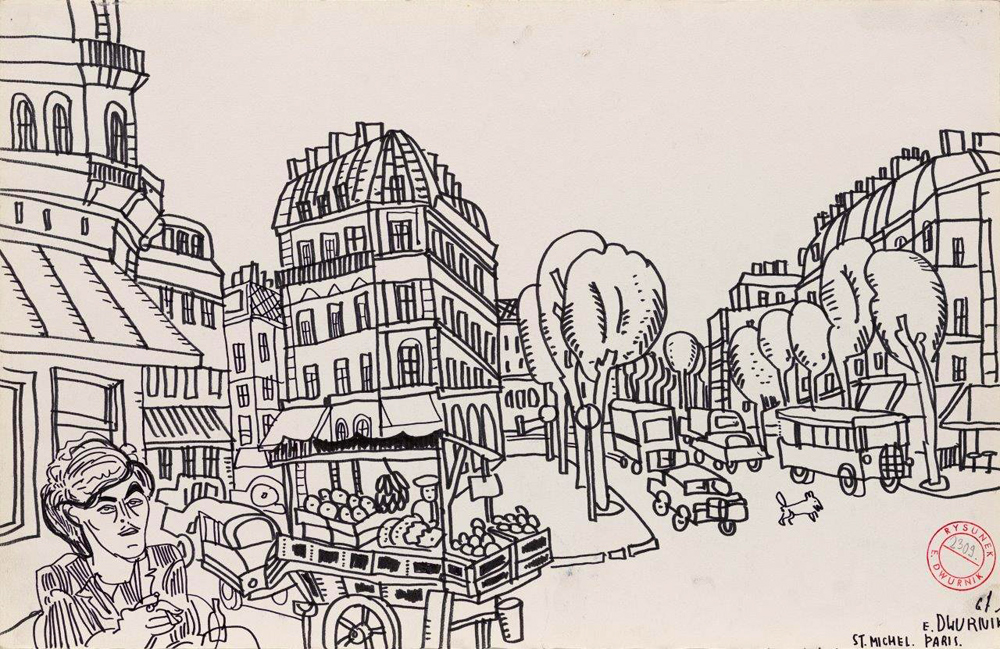

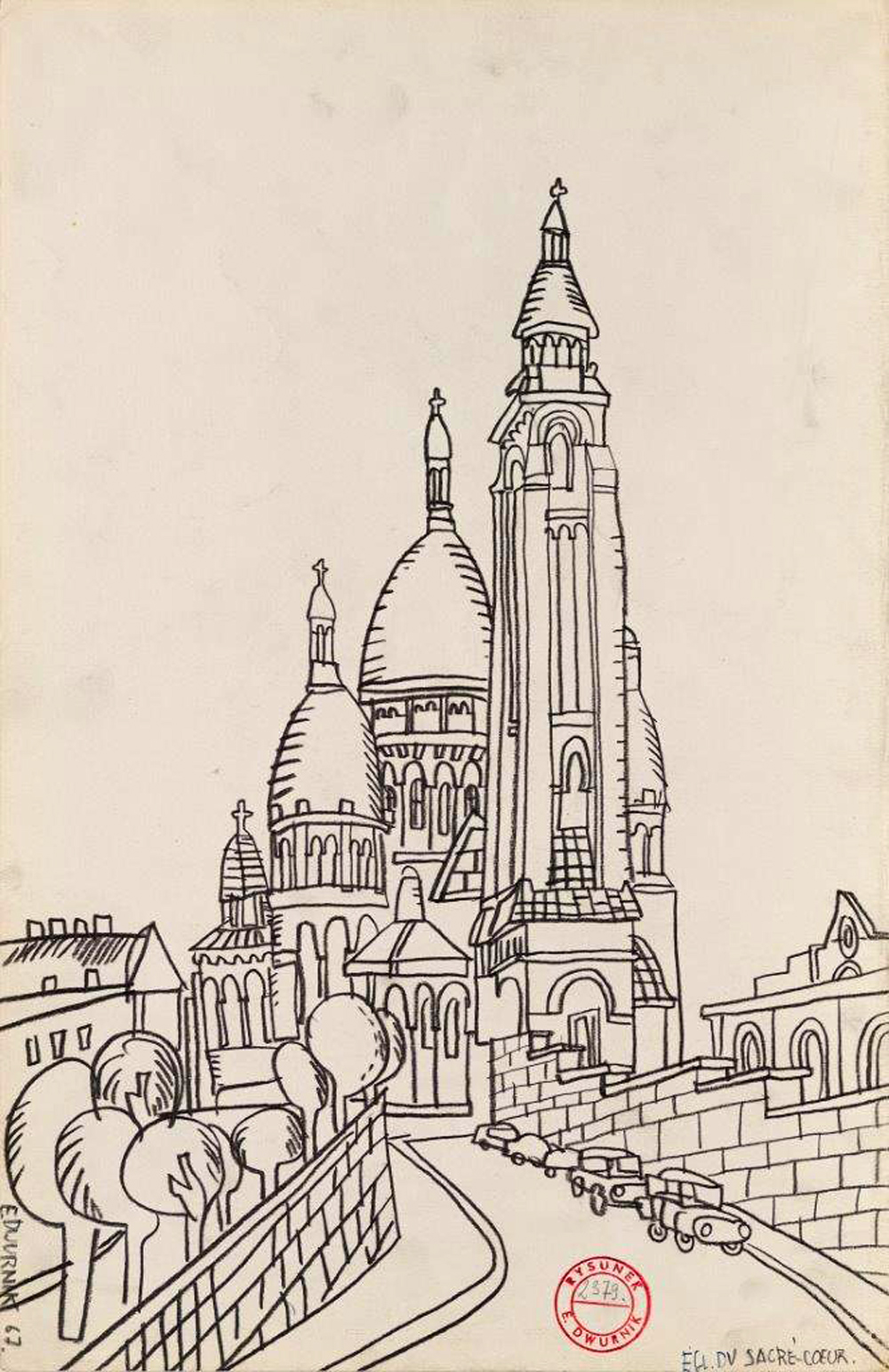

In 1967 I went abroad for the first time. To Paris. I was a student at the Academy of Fine Arts at the time, and I drew non-stop. I pretended to be Nikifor and went gallivanting around Poland with a (…)

In 1967 I went abroad for the first time. To Paris. I was a student at the Academy of Fine Arts at the time, and I drew non-stop. I pretended to be Nikifor and went gallivanting around Poland with a sketchpad and pencil. Every artist dreams of Paris, and I also wanted to compare the real thing with what I’d seen in the beautiful black-and-white photos in the books that the Academy librarian Mrs Grabowiecka used to find for me. The Academy already had a fantastic collection of books at the time. I looked at countless photographs of Paris. On page after page I gazed at streets and squares; there weren’t many trees, so the architecture was readily visible. I also loved the lithographs of Bernard Buffet, who often depicted Paris, and I wanted to draw like him for a while. But going abroad was no simple matter at the time. My friend Ewa Kuryluk helped me procure an invitation. She wrote to someone she knew in Paris and that girl invited me. It was very kind and disinterested of her, and I never even met her.

My suitcase was packed to bursting point with food. I was carrying sausage, Portuguese sardines, the famous pressed ham in red tins that had ‘Ham’ in English on them. My father gave me three litres of vodka in six half-litre bottles. I was to sell them. I had 100 dollars hidden in the hollowed-out heel of my shoe. I didn’t speak a word of French, but so what? I was a kamikaze! I remember I took a bus from the airport, and then the underground. I got to Boulevard Saint-Michel and found a small hotel in some back street. The guy at reception gave me a room on the fifth floor, and I had to drag that suitcase all the way up; I barely managed it. I was so stupid that I paid for a whole week upfront. He took some 400 francs off me, but I still had a little left over. (Before long, an acquaintance from Międzylesie who was working in Paris as a household help found me a room with a family, and I moved out of the hotel; I even got some of my money back.) Once in my room, I opened the sardines and vodka, had a drink, unwrapped a baguette I’d bought on the way, and after eating I went out to buy paper and pencils. In the student quarter I found a small shop selling art supplies. I bought pencils, soft pencil leads, a nice green sketch pad. Then I went to a café, where I had a few glasses of wine and started drawing. I ended up drawing the length and breadth of Paris. After one and a half months, I returned to Poland with 118 drawings. There had been many more, only I’d left one big folder on the underground out of absent-mindedness. And I don’t even know if those drawings were signed. My Paris drawings seldom include people or action, for I was concentrating exclusively on architecture. People in pictures make sense if they add something, if they enrich the composition, but here it was the city itself that played the main role, and there was no point in making things complicated.

The obstacle, or a walk in Rypin

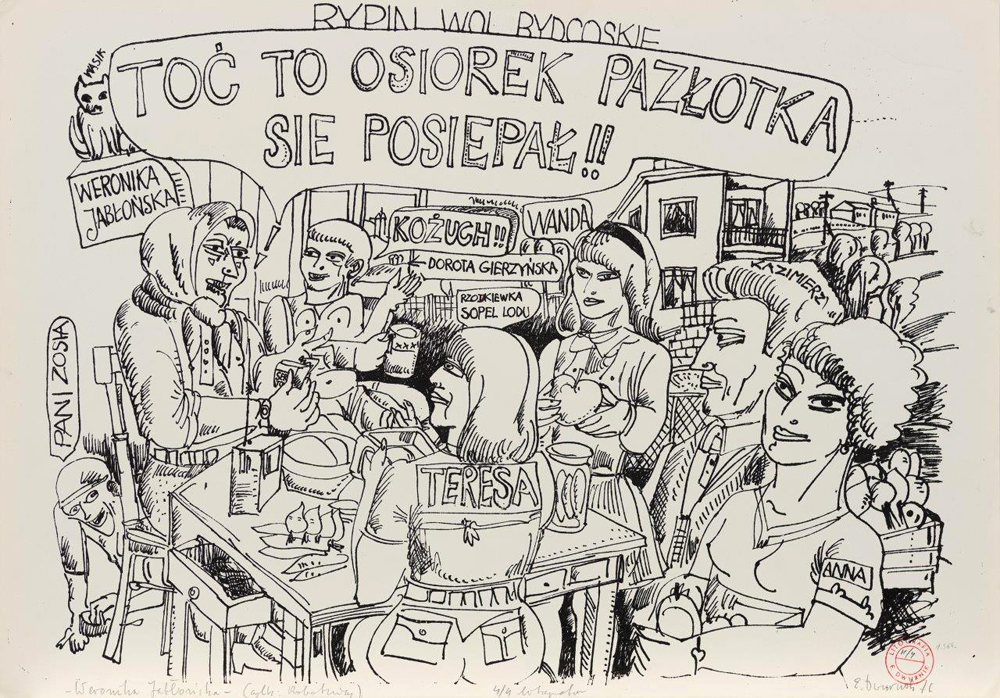

In this drawing Tereska Gierzyńska and myself are going for a walk in Rypin. It’s either towards the end of our engagement or early in our marriage. We’re all dressed up as we walk, but in front (…)

In this drawing Tereska Gierzyńska and myself are going for a walk in Rypin. It’s either towards the end of our engagement or early in our marriage. We’re all dressed up as we walk, but in front of us there’s a drunken man lying on the pavement - an obstacle, a hurdle.

I met Teresa at the Academy or, more precisely, at a party at Ewa Michalska’s, a college friend. Ewa’s parents had gone away on holiday and left her the run of the place. We danced to the songs of Salvatore Adamo and a lot went on that night, with any number of male-female connections and relations being started. Later I even told Professor Eugeniusz Eibisch that I’d met a nice girl and that I was going to marry her.

Teresa’s parents and her younger sisters lived in Rypin. Her father was a barrister. One summer they went to a sanatorium in Ciechocinek. Teresa let me know that she was home alone and invited me to visit her. My style at the time was modelled on Nikifor: I had a handlebar moustache, long hair, plus my father’s jacket. I caused a sensation. One day we were walking around Rypin and we met the local judge, who later asked Teresa’s father who the young man was who was hanging around his eldest daughter. And her father told him I was an artist, a friend from college. Everyone was very interested in us. One of the neighbours asked me what I was doing there. Teresa’s parents worried that people in Rypin would talk, but when it turned out we were going to get married, they calmed down. The wedding took place on the 20th of October 1968 at the registry office in ulica Mycielskiego in Grochów. The party was in my home in Międzylesie: the official reception downstairs at my parents’, and the second part, for our sculptor and painter friends, upstairs in my studio.

Silver paper

In 1976 I made a lithograph of a breakfast scene in the family home of my wife, Teresa Gierzyńska, in Rypin, Kujawy. For me it’s just an ordinary scene, a memory of a morning at my in-laws. We (…)

In 1976 I made a lithograph of a breakfast scene in the family home of my wife, Teresa Gierzyńska, in Rypin, Kujawy. For me it’s just an ordinary scene, a memory of a morning at my in-laws. We often visited them, at first in our first Beetle, then in the second. It was idyllic. The house was small – 110 square metres, in accordance with the regulations of Gomułka’s time – but it had a garden. And there was an orchard on a slope, with lots of gooseberries, which Pani Weronika, the family’s servant, made into delicious preserves. We ate those gooseberry jellies and jams non-stop. And now, searching in my memory for forgotten words, I’ve realised that I recorded one such word on the lithograph, a word that I think has gone out of use, at least I don’t hear it anymore, and I never use it myself. For me, that word is forever connected with Pani Weronika.

When I first met her she must have been around sixty, and she seemed old to me. She had a distinctive feature in her appearance – something she probably considered a flaw – the intense redness of her face, so-called ‘fire’. She ruled the house. She was a specialist in floormopping (in a concentration camp during the war that skill had reportedly gained her recognition from the Germans, plus extra portions of bread and margarine), in chopping off chicken’s heads (my father-in-law, a provincial barrister, and much in demand, kept receiving gifts of poultry from grateful clients), in stuffing the birds. Her cookery was to die for. There was just one thing Pani Weronika wasn’t good at, and that’s what this breakfast story is about.

There are several people at the table: my in-laws, Anna and Kazimierz, and the Three Graces, Teresa and her younger sisters Dorota and Wanda. The daughters of Mr Gierzyński the barrister were not only beautiful, but also talented. They all studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. So we’re sitting at the table, the cat Waśko keeps climbing onto our laps; there was always some cat or other there, and at that time it happened to be Waśko. It’s a pleasant morning, we’re talking about nothing in particular, although it could be that my father-in-law was trying to get me to discuss politics. He liked to talk politics; he enjoyed reminiscing about how in 1956 the whole town of Rypin shook as Russian tanks rolled down the main street. But the girls and I are waiting for the high point of the breakfast: Pani Weronika’s struggle with the cheese-spread wrapped in silver paper, or aluminum foil if you prefer. Pani Weronika would invariably squash the cheese, tug at the wrapping, rip it the wrong way; her fingers got sticky, the cheese spread got under her fingernails, and she’d always say: “T’ silver paper’s a right mither”. Every time she said it, without fail! Nobody wanted to eat the cheese spread anymore, but we laughed such a lot at that saying of hers, her cheese mantra.

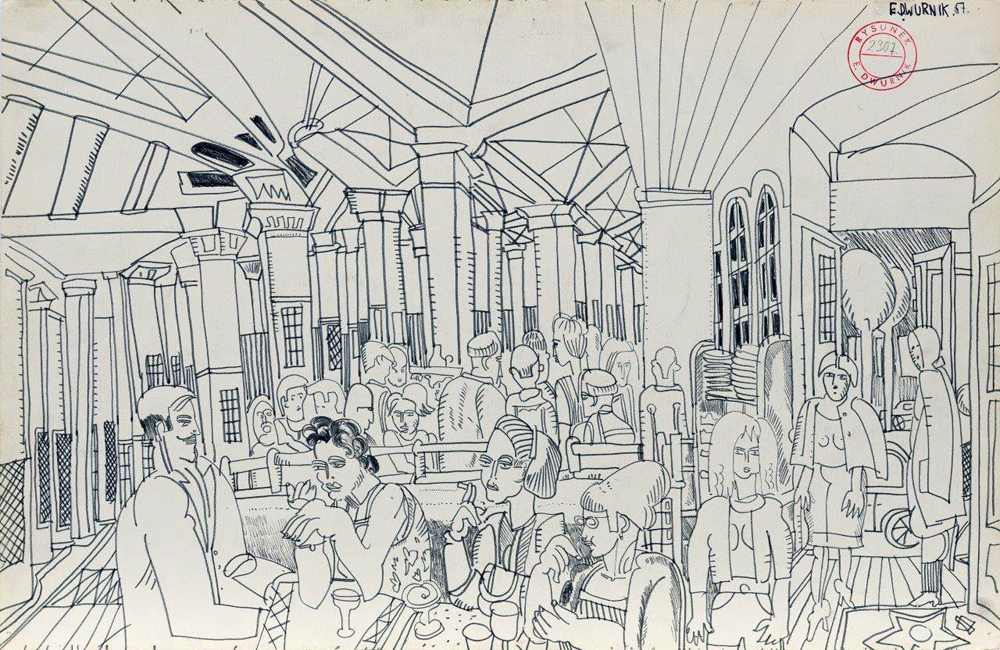

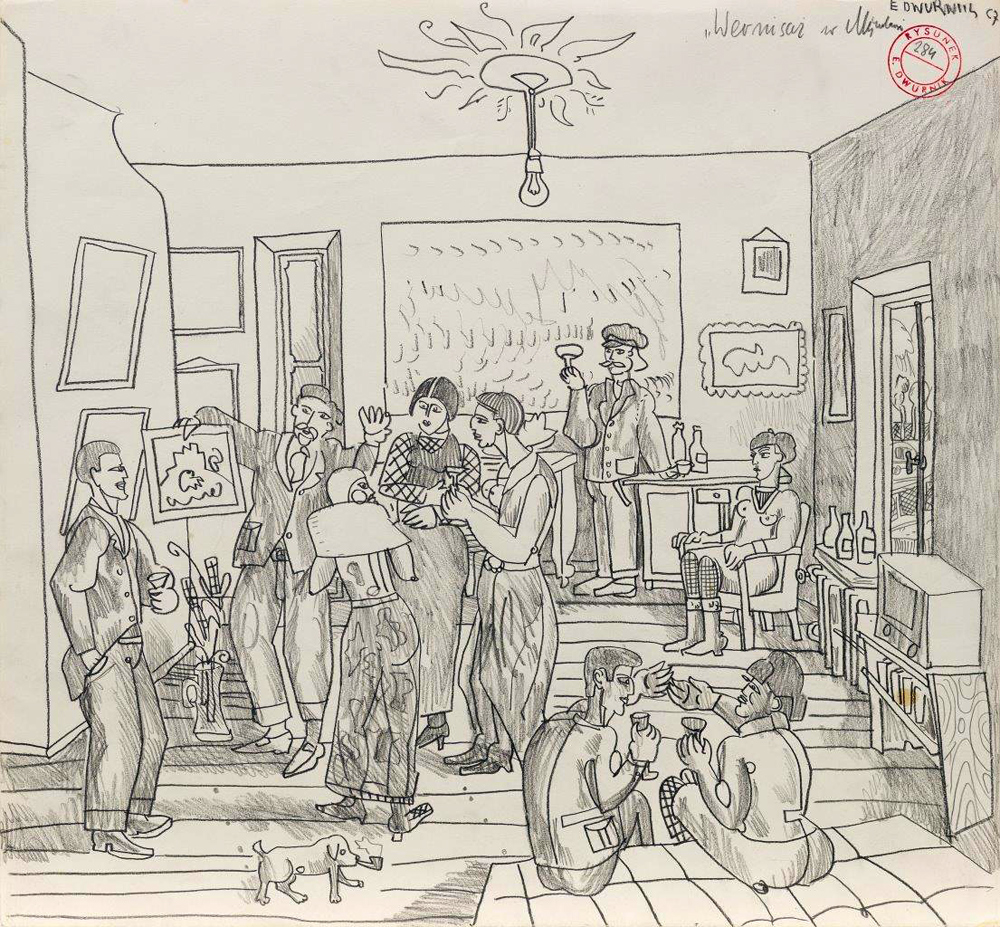

A lot of practice

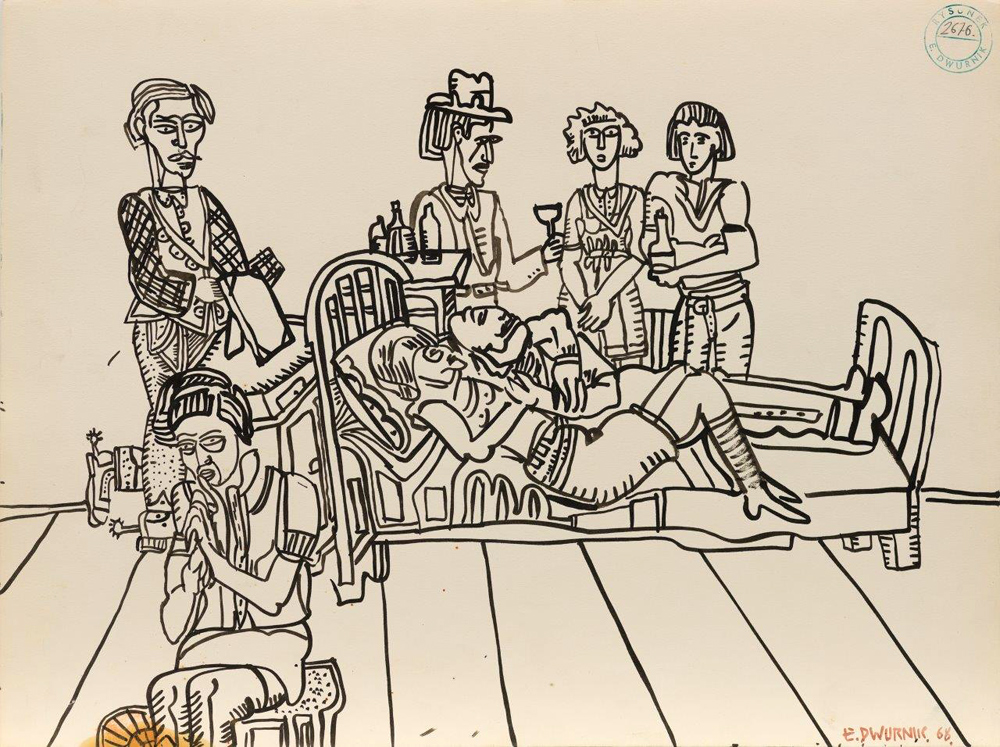

There were always parties at the Academy. There were the more civilised house parties, like the one at Ewa Michalska’s where I met Teresa, as well as other, more primitive ones in Dziekanka, where (…)

There were always parties at the Academy. There were the more civilised house parties, like the one at Ewa Michalska’s where I met Teresa, as well as other, more primitive ones in Dziekanka, where Myjak and Frąckiewicz used to organise total piss-ups. Everyone would sit on beds and swill beer straight from the bottle. Boozing is a normal part of student life. My friend Przemek Kwiek really celebrated such situations. We’d both had a lot of practice at the secondary school for adults in Otwock. We would go out with a bucket to get more beer, or we’d buy vodka, bread and fresh ham; it was still possible to get ham in those days. I remember how once we got stinking drunk and emerged from the basement, where the lithography studio was, into the courtyard. Other students were basking in the last rays of the sun. One of them was the sculptor Paweł Jocz, and he shouted to us: ‘Go get some lemon, that’ll sober you up.’ At other times we would go to Fukier to drink wine, or off for a quick shot of vodka in Pani Stasia’s dive.

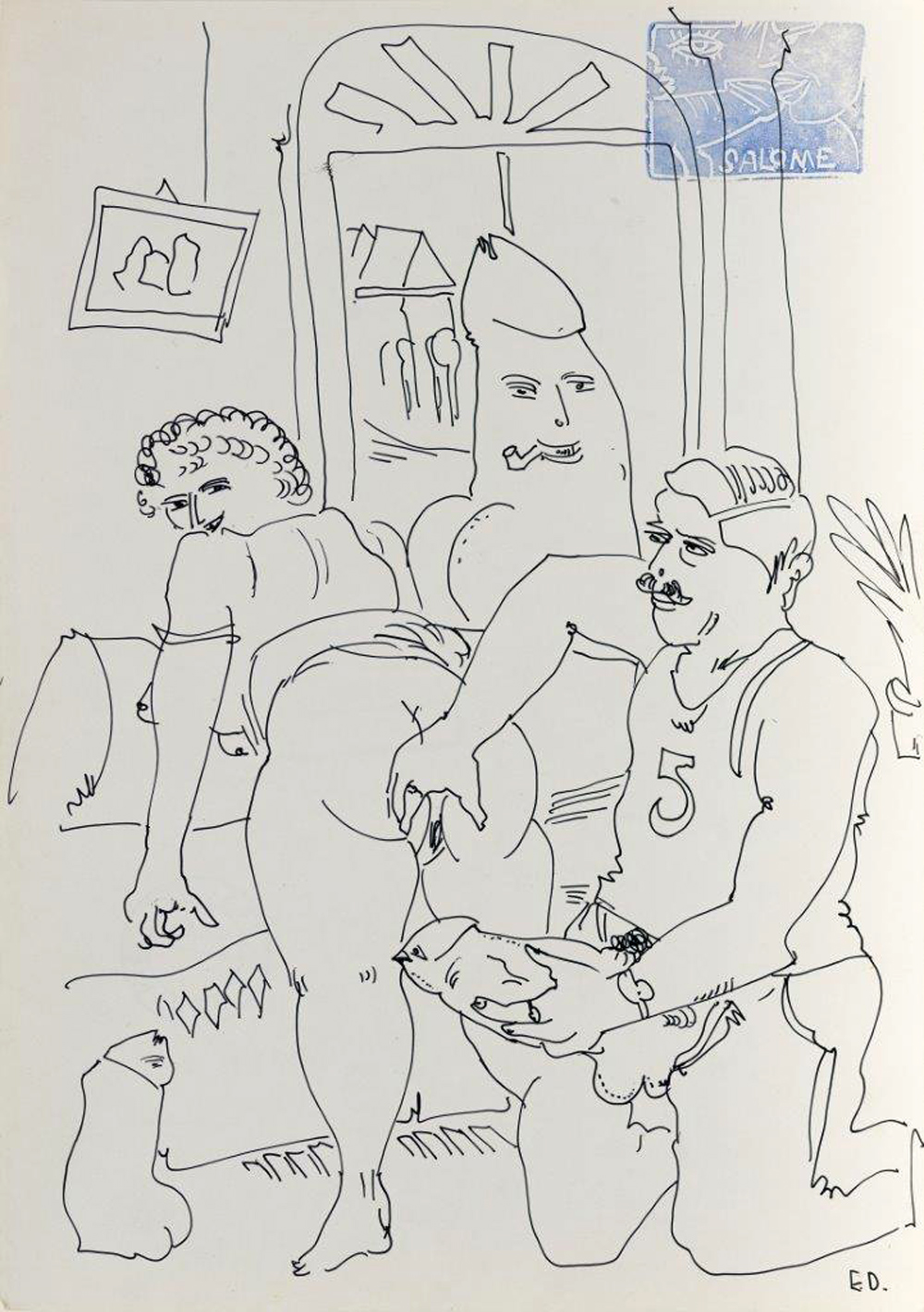

Saved

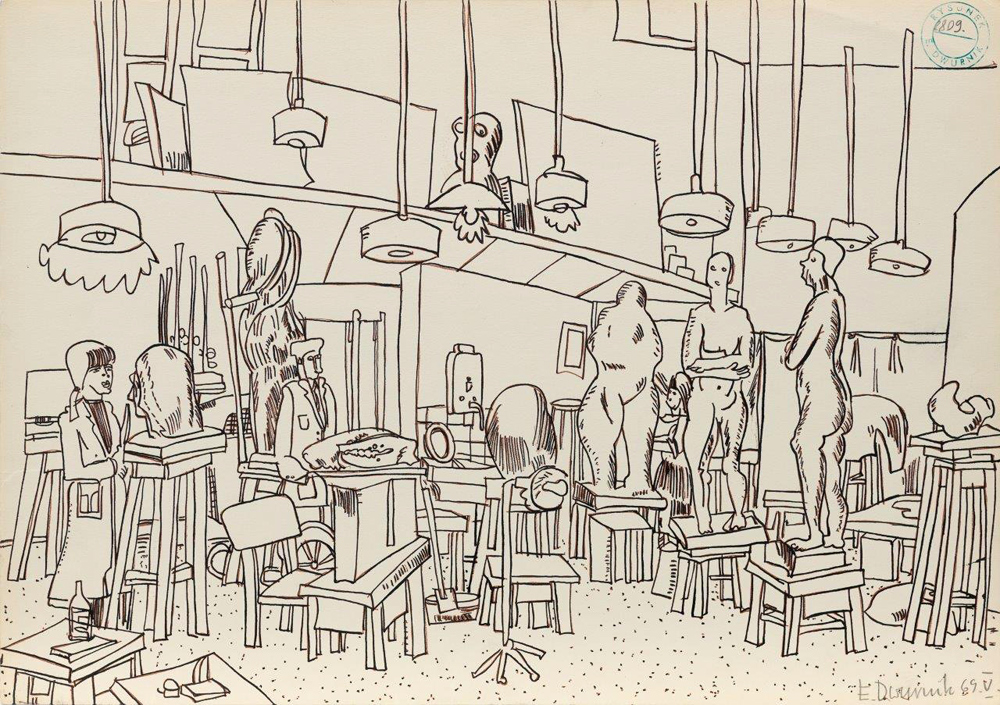

This is a story of my stupidity and the magnanimity of Teresa, my future wife. It looks like an innocent scene in a sculpture class, but I’m immediately reminded of a dreadful incident which almost (…)

This is a story of my stupidity and the magnanimity of Teresa, my future wife. It looks like an innocent scene in a sculpture class, but I’m immediately reminded of a dreadful incident which almost got me expelled from the Academy. My mates and I got terribly drunk once before going to our sculpture class in Jesion’s studio. There were wet sculptures standing there, nudes, wrapped in cloth so they wouldn’t dry out. And we, stupid drunks that we were, pushed them over. Jesion asked Tereska to identify the perpetrators, but she didn’t. If I’d been expelled then, things would have been really bad for me. In a word, she saved my life.

The soda cart

During my time at the Academy there was a model there whom everyone knew. His name was Ignac. Thin, bespectacled. Take any Academy publication and you’re sure to find a photo of Ignac, or a (…)

During my time at the Academy there was a model there whom everyone knew. His name was Ignac. Thin, bespectacled. Take any Academy publication and you’re sure to find a photo of Ignac, or a sculpture for which he posed, or a painting. In the summer, when he had a break from posing, he used to hire a soda cart and stand with it by the entrance to the Tenth Anniversary Stadium, where he sold soda with syrup. The glasses were attached to the machine with a chain. They were popularly called ‘TB glasses’, as they weren’t properly washed. But somehow no one was especially bothered about hygiene.

This drawing was made on Bristol paper bought in Reszel. Sometimes you could come across good materials in small-town shops. My friend Przemek Kwiek and I once got a job in Reszel: we were painting the walls in the local church, and I was also doing some frescoes. We went to a chemist’s there, and they had a ream of fantastic Bristol board. I bought all they had. It was heavy as hell, and I had no car at the time, so we had to take it on the bus; Kwiek was cursing to high heaven. Later I cut it all into smaller sheets and made drawings, which I’ve kept to this day. It was beautiful paper, although it did yellow a little with time.

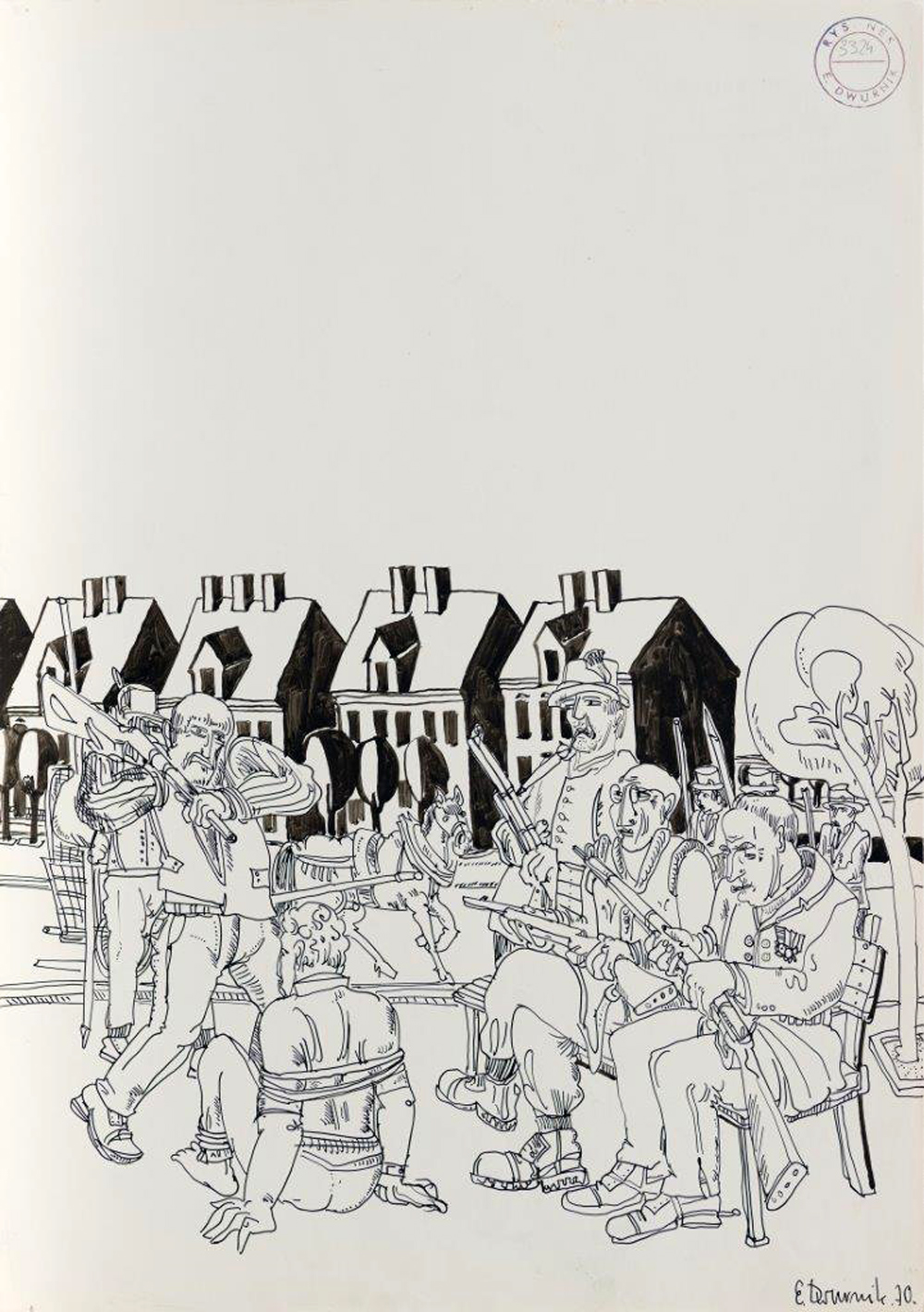

No room for the sky

I’ve always fed on crowds, and that’s plain from these pictures. There was a stage I went through when there was no sky in my pictures, because I grudged the room for it. I filled every bit of (…)

I’ve always fed on crowds, and that’s plain from these pictures. There was a stage I went through when there was no sky in my pictures, because I grudged the room for it. I filled every bit of paper with densely-packed little humans. I drew a dense crowd, but I always tried to make the figures different. A human in space is like a little blot, right? But I would adorn each one of them: give them hairstyles, costumes, a sword, spurs, a hat with a feather, and all at once each little human would gain individuality. Later, when I painted Hitchhikers and Athletes, where such characters might be met in different situations on the same canvas, they also became adorned in various ways, with a tight belt around the waist, or holding wheels of some sort, or they might be knights. I did the same thing as in the drawings. It was an escape from realism.

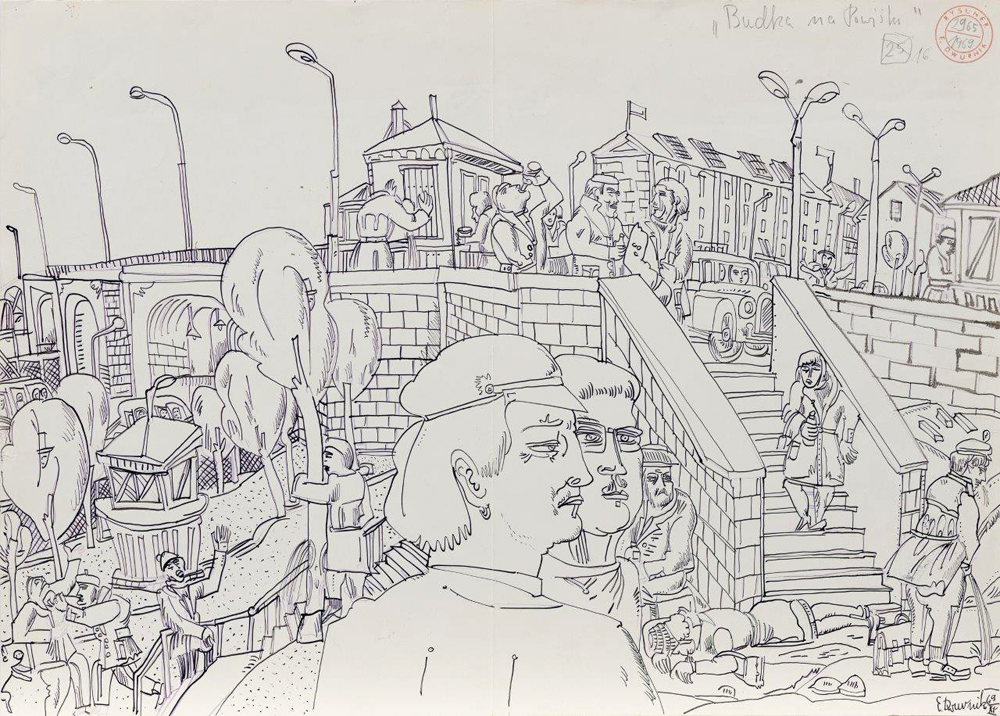

Style

The guy in the foreground of this drawing is me. I’m wearing a cap with a shiny peak. I had several of them, all bought from the well-known hatter Modzelewski in Aleje Jerozolimskie. I even made a (…)

The guy in the foreground of this drawing is me. I’m wearing a cap with a shiny peak. I had several of them, all bought from the well-known hatter Modzelewski in Aleje Jerozolimskie. I even made a stamp showing my profile in this cap, and it appears in many of my works. As for other objects of desire from the time of my youth, there were the fashionable striped shirts that you could only buy in small private shops in Praga; then there were jeans, preferably Lee’s - I had a pair with checked lining. Later, white non-iron shirts came in, as well as navy blue raincoats. There was also the Stopa cooperative – they had a shop in Nowy Świat where they sold suede shoes. Everybody was crazy about those shoes.

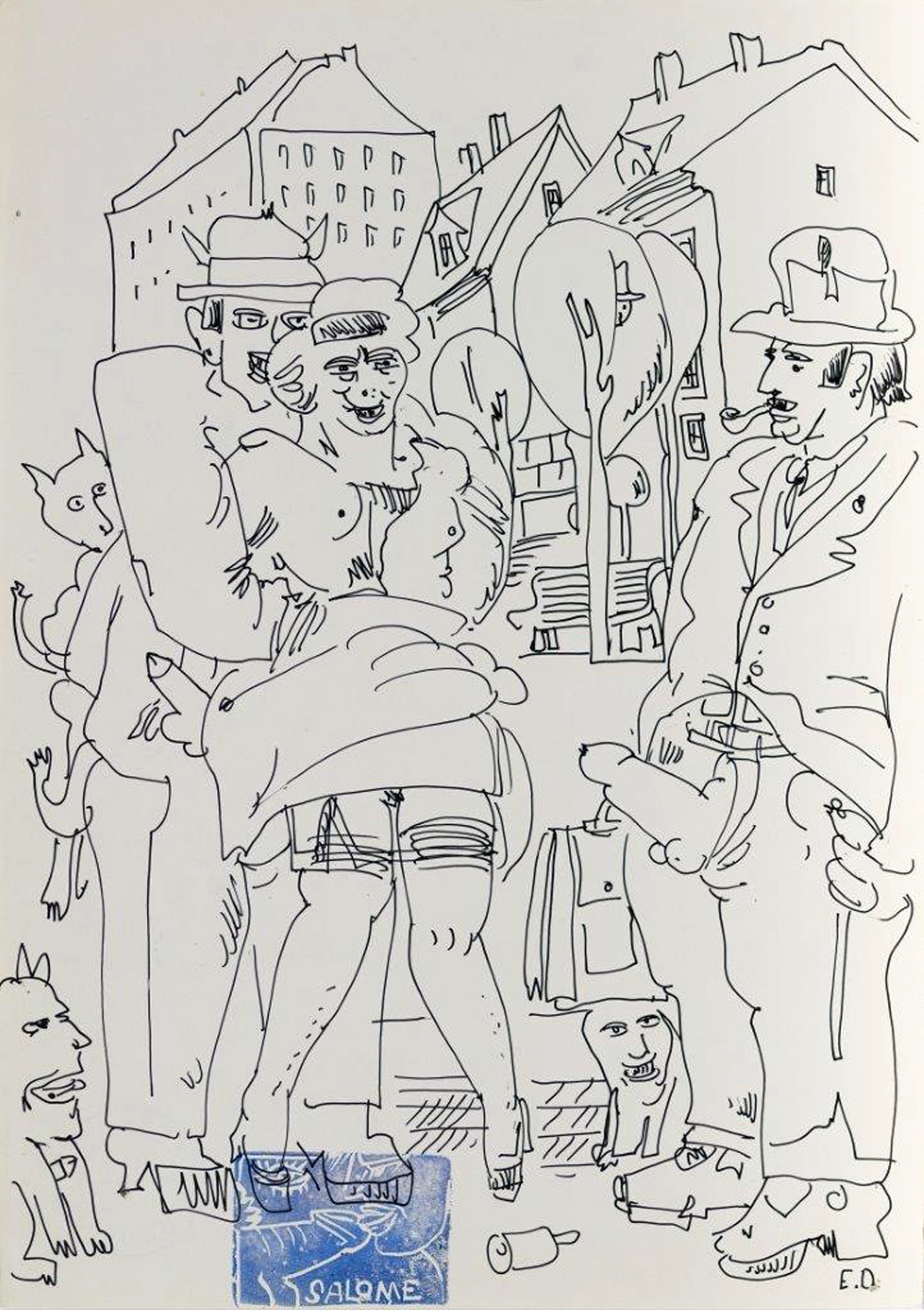

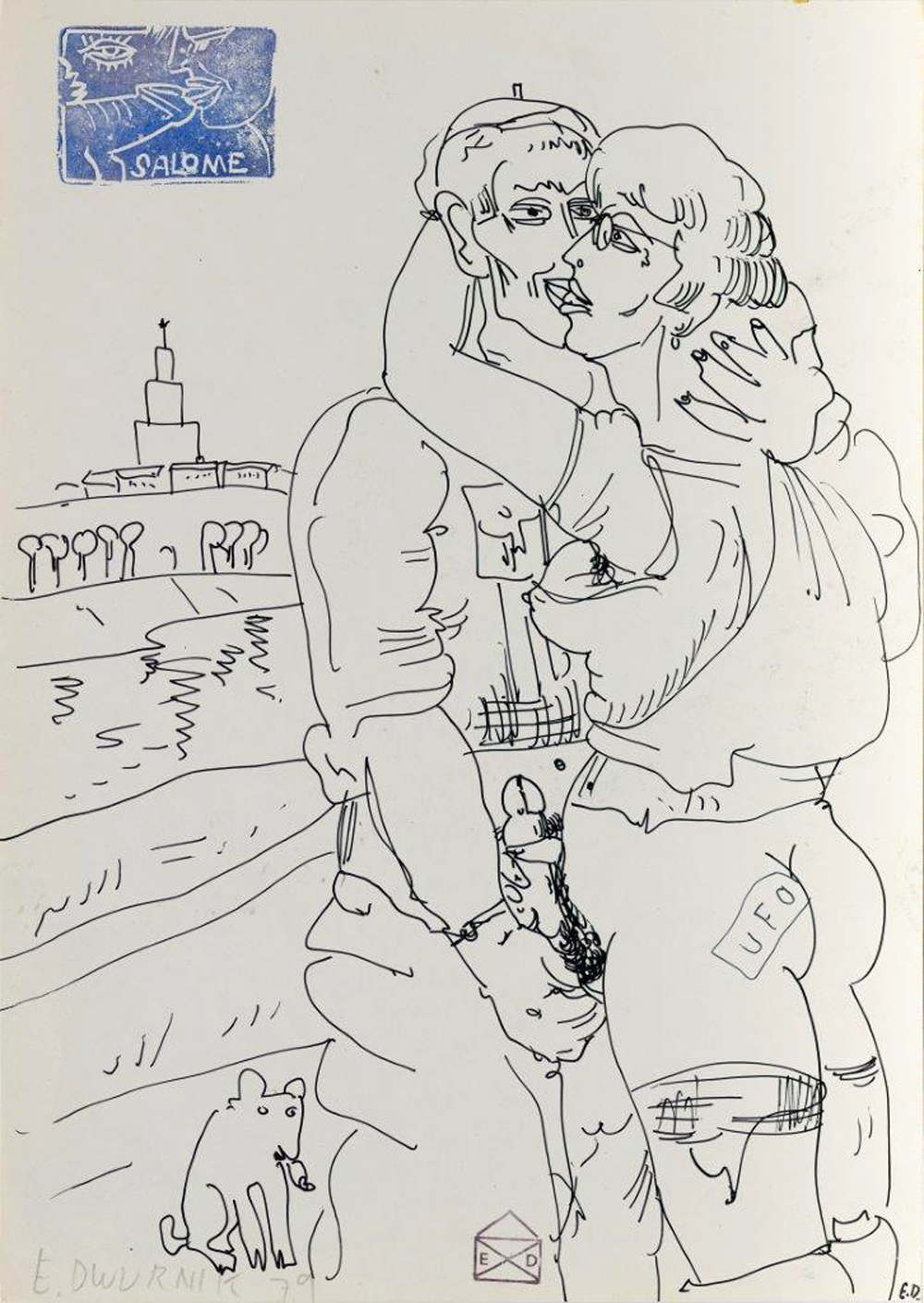

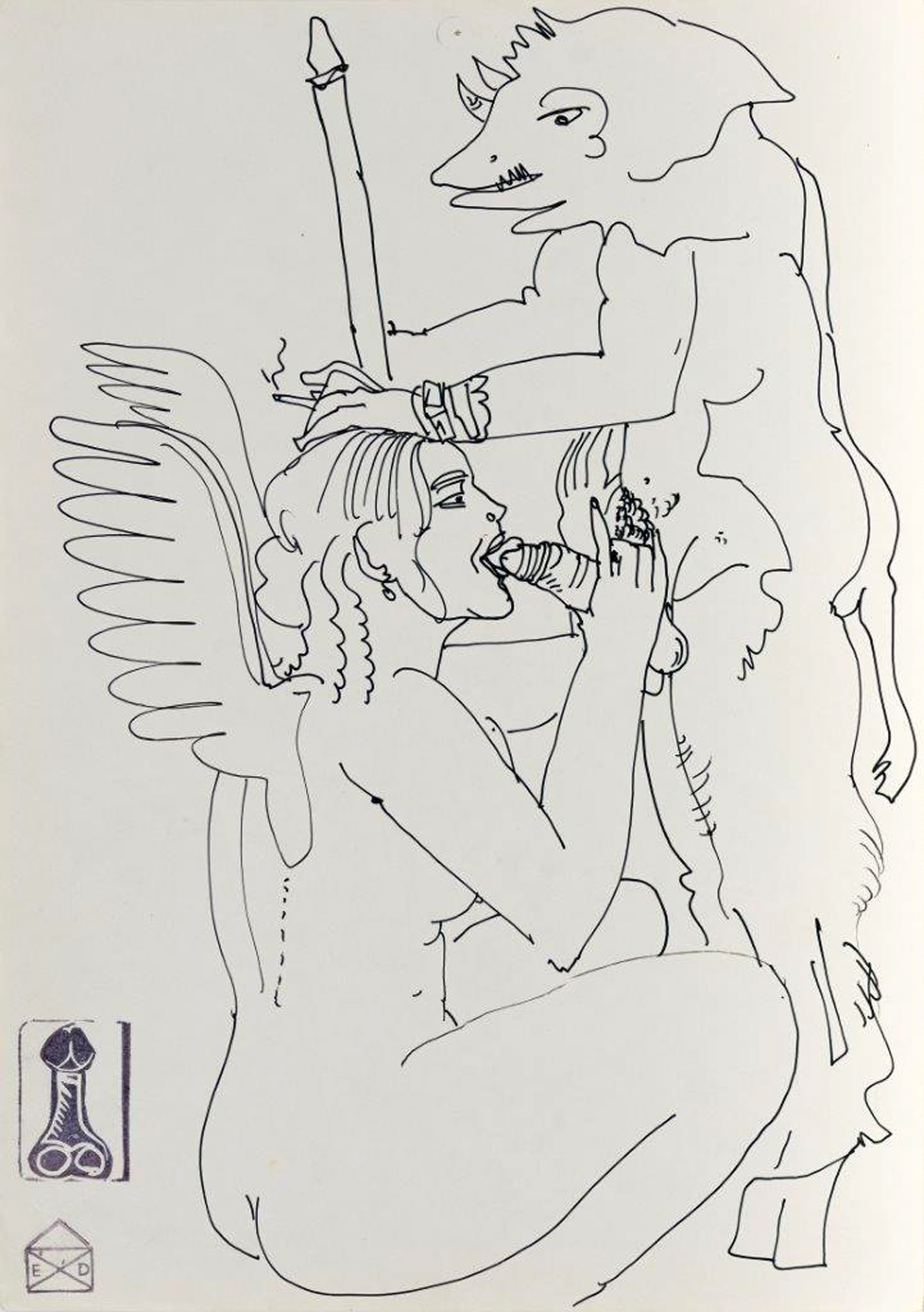

Erotica

There’s not much to explain; you can see it all. Phalluses everywhere. They say money rules the world, but so does the phallus. I didn’t mean to draw pure pornography, although I’ve produced a (…)

There’s not much to explain; you can see it all. Phalluses everywhere. They say money rules the world, but so does the phallus. I didn’t mean to draw pure pornography, although I’ve produced a lot of erotica, especially when I was young, and of course there is a certain pleasure and excitement in that. But there’s also a substantial element of comedy in these drawings. As big as a huge prick.

Bare arses appear in many of my works, even in those that are not about sex. People’s trousers are always falling down. It’s a simple trick: say you’ve got a picture of the queen of Britain in a suit, OK. But if I draw her knickers, it’s more fun and more interesting. And if those knickers fall down, that’s even better.

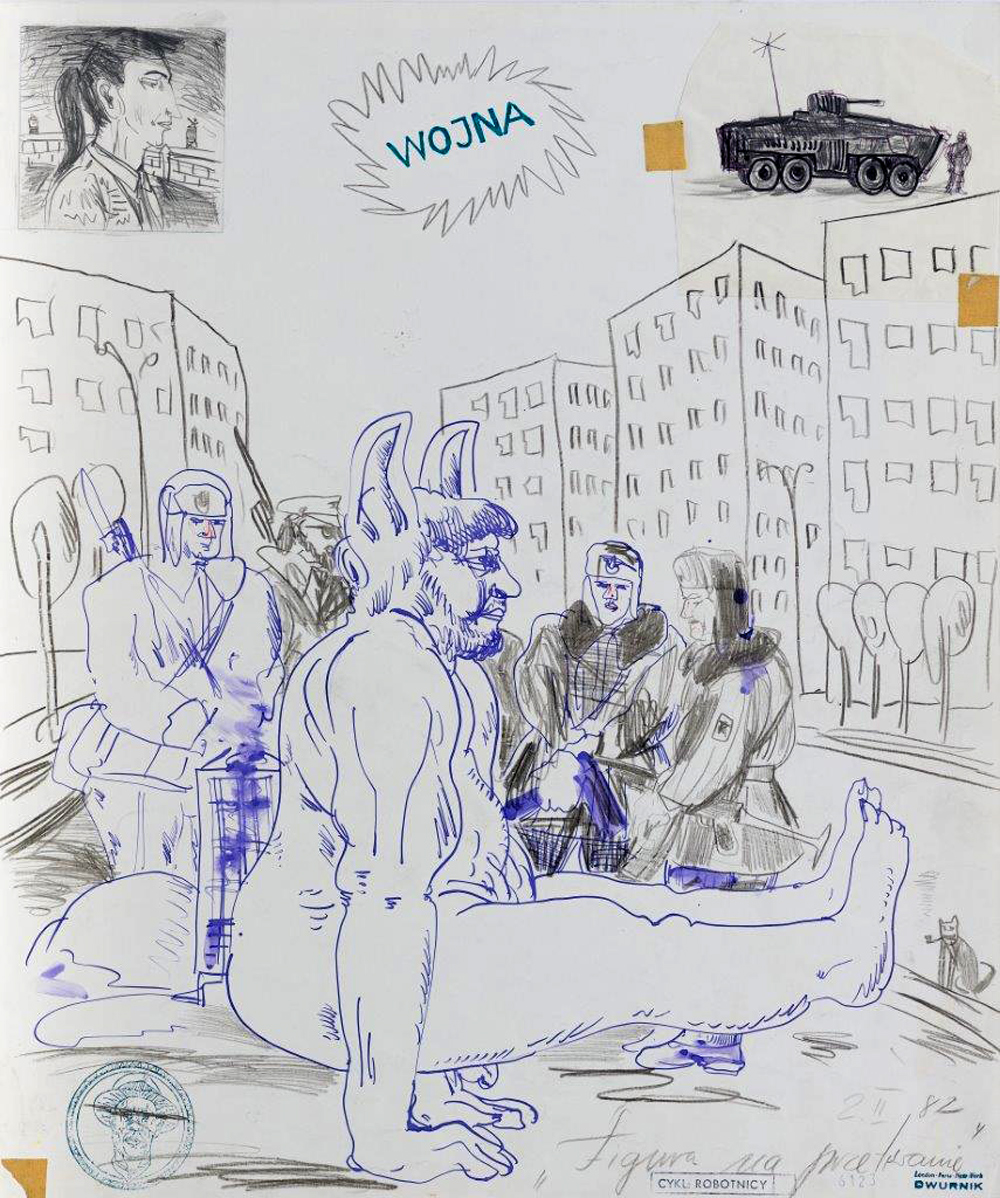

The survival figure

You mustn’t imagine that the motif I call the ‘survival figure’, which appeared in my work in the 1980s, had anything to do with the political situation then. It’s a neutral idea. I have my (…)

You mustn’t imagine that the motif I call the ‘survival figure’, which appeared in my work in the 1980s, had anything to do with the political situation then. It’s a neutral idea. I have my own private jokes: a severed head, a dog with a pipe, a cat with a pipe, copulating dogs and many others. A survival figure is a guy supported on his hands, with his legs extended horizontally. It’s a difficult position to hold; I’ve often attempted it myself and couldn’t manage it. When I was doing boxing in the 1960s, I had stronger arms. I liked the ‘survival figure’, so I put it in various drawings and prints. I still have about a dozen works in drypoint in my drawers, showing a police patrol standing by a coke-burning rocket stove made from a bucket, and in the foreground there’s a dog-man with a dangling prick who’s supported on his hands. But people started to imagine a symbolic meaning behind my ‘survival figure’. That’s what happened at my large exhibition in the Kunstverein in Stuttgart, in 1994. I showed some drawings there, three cycles from my debut exhibition in Bogucki’s studio: the Plaster PleinAir, Various Blues and The Road, as well as lots of paintings: the Athletes, the Workers. The curator was the director of the Kunstverein, Martin Henschel. The Germans made a beautiful book of this exhibition, and it opens with a reproduction of the ‘survival figure’, as if that was somehow the key to understanding my art.