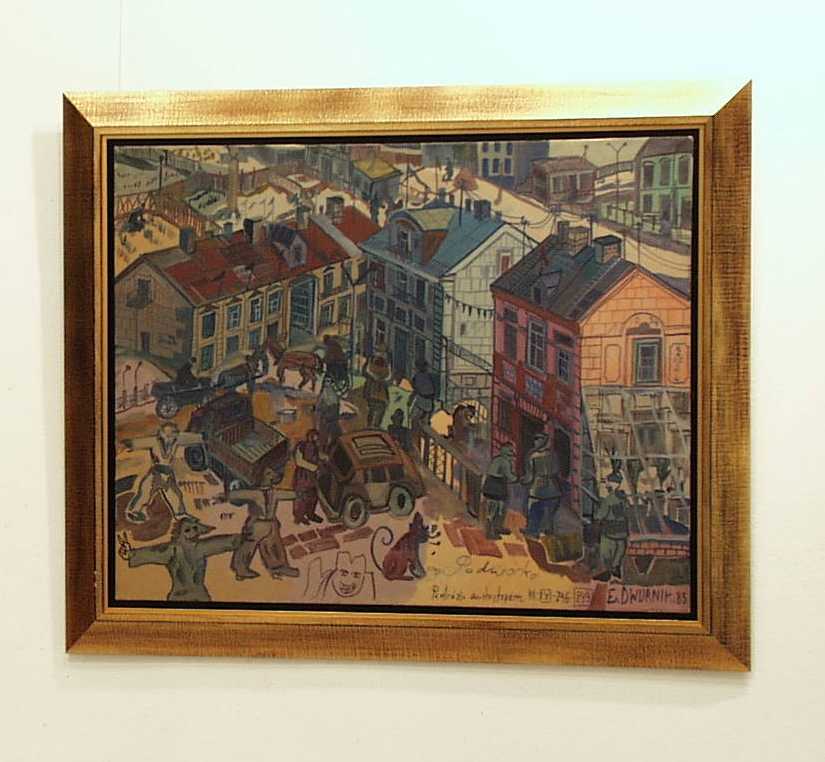

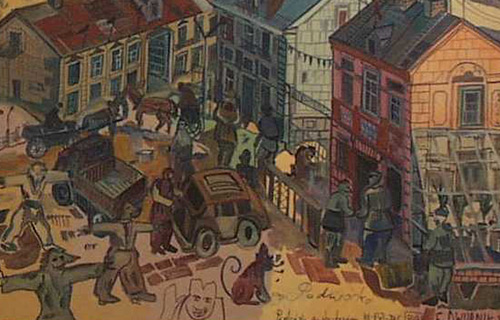

My Yard

Edward Dwurnik painted his Moje podwórko (My Yard) in 1994 as he was back from his yearly scholarship in Germany. After his stay in the West he could all the more painfully feel a contrast between the European level of life and the Eastern-European style. His family town of Radzymin was, according to his paintings, a symbol of all that Eastern-European anarchy, chaos, and mess.

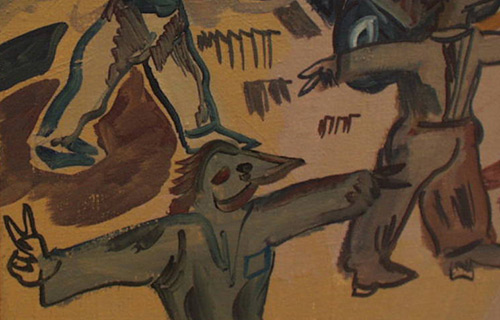

The said picture presents more animals than humans. Dwurnik has often painted humans in an animal disguise. These too are humans in the form of animals. A dog is betrayed, however, by the 'human' pipe he holds in his mouth. The animals wander through the yard from the left-hand side of the painting to the right, their movement stretching as if beyond the picture's frame. This is an eternal move, a migration.

The year 1984 was for Poland the sad time of the martial law, political repressive measures, and social torpor. Every once a while, people from Dwurnik's milieu emigrated one by one. Those 'better ones', speaking foreign languages, would obviously emigrate to America or Western Europe. Those 'worse ones', poor people, would move into another locality or perhaps, the capital town, to work in a factory. Also those who happened to die, did 'emigrate' as well.

This leads us to see the painting as showing a concrete place, a house in Mickiewicza Street in Radzymin where Dwurnik lived as a child, but also does it show Poland as a 'transit' place, not quite suitable to live in. Early in the eighties, everyone urged Dwurnik to leave Poland. And he had several opportunities indeed to do so. Yet he held out and stayed in his country, for it would all become even worse for him wherever else. Today, he stands out as the best-known Polish artist.

Moje podwórko is also an example of town-planning and architectural styles proving typical to the part of Europe we inhabit. Polish small towns are incessantly picturesque. We can always find there some nice architectural details, and a good deal of mess. Traces of some better times in the rich ornaments of architectural specimens coupled with those of our contemporary muddle. No-one cares about those houses, they belong to the state, their former owners have been dispossessed. No-one may renovate them, or celebrate living in them. It's just that people happen to live there; they live their simplest, natural lives, 'just for the time being'.