Early in the morning

Łowicz V, Vii, XIV, XVIII, from the pencil-drawing cycle ‘55 Auto-Stop’ [55 Hitch-Hiking], 31 x 49 cm, 1966.

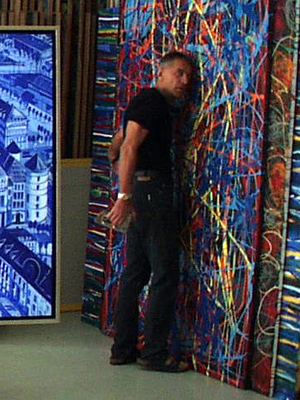

Early in the morning of June 4, 1966, Edward Dwurnik got off a train at the platform of the railway station at Łowicz. He was not wasting his time, as the first drawings were made after only thirty minutes. Tracing their numbering (Mr. Dwurnik is a careful archivist indeed) one may make a guessing that on that day, almost thirty works were created, lane by lane, sight by sight. On that same day, Dwurnik was drawing and drawing until it got dark, taking just one break to have a bun with a piece of sausage. He started taking any care about someplace where to put himself up for the night just when it was getting dark. At the town market, right above the ‘Łowiczanka’ restaurant, he found two ‘guest rooms’ available: one for men and the other for ladies, fifteen beds in each. Since the men’s room was occupied by drinking lorry drivers, the service staff sent the art student from Warsaw to the other one, as there was no-one at that moment. An hour later, four women entered the room, took off their clothes, and went to their beds. Dwurnik can well remember their pink slips and nylon bras. He actually spied on them from underneath his quilt before they switched off the lamp bulb. They got up early the next morning, to be on time at the local Corpus Christi celebration. As they were marching in a procession, he was on his way, hitch-hiking to reach, within a couple of hours, the town of Skierniewice, where he got down to drawing again. Having finished one piece he started walking again, but he could make only some twenty steps and then would stop and unfold his sketchbook – after all, he could then see something new again! Never imbued enough with images, always avaricious and jealous about any detail. The same happened over the next days, in Pabianice, and in Zgierz too, the places he reached by the then not-yet-existing longest cable-car route in the Eastern Europe. Łódź was the only place where he made no drawings at all. The enormous bourgeois tenement houses discouraged him; at the time, he was not yet ready to meet their challenge. This one of the many hitch-hiking journeys got to an end after a fortnight, in Paczków of Silesia. A night at a railway station. Having caught a cold, he was waiting for a morning train to Warsaw. And, he could spend his last pennies but on two teas with sugar.

The artistic means used in those early works boiled down to a minimum: only few sorts of a reasonably soft pencil against a quality paper sheet, expensive in terms of his being a poor student then. Taking a closer look, we can even count how many times he had to sharpen his pencil to finish up one piece. The whole cycle seems formally to be uniform only at the first glance. Taking a closer look still, a line may tell us more of a story, and sometimes, it can reveal everything: one’s being euphoric, exhaustion, impatience; it can show off satisfaction, disclose a haste. A line is whimsical when tasked with laborious ‘remaking’ of the cobblestones and shaky fences; it gets more serious as it climbs a church tower to crown it with a baroque helmet. The eye can do the job with even a most complex foreshortening. Who doesn’t know that in the land of Mazovia, the utmost challenge for any town landscape maker is Bednarska Street, in the Warsaw district of Mariensztat. Not only does it head acutely downwards but makes a curve at the end. Dwurnik has once made, on a routine basis, a version of the view, for the use of his friends, Architecture students. These paid him back – with sheets of rationed ‘Ingres’ paper, that luxury commodity onto which he then redrew Łowicz.

Dwurnik focuses on the town’s here-and-now, whereas through the humdrum of the Gomułka period (1956-1970), the times of historical splendour of the city pushed their way, with the Primates’ residences – a Polish Salzburg, as measured against our ‘unleavened’ national standard. The architecture persists, and triggers respect by virtue of its eternal existence. It is through the facades of these tenements that history of Europe speaks – at times, lofty, some other time, commonplace.

Ruskie radary. Przejazd do jednostki. Plac wolności. Śniadanie na kacu [Russian Radar. On the Way to the Military Unit. Liberty Square. Hangover Breakfast], from the pencil-drawing cycle ‘54 Kołobrzeg’, 34 x 49 cm, 1969.

The year 1969 came three years after. A summer again. Dwurnik goes for a week-long open-air session at a military unit in Kołobrzeg. Again, his hands appear abundant with drawings. The life in barracks, the life on holiday, the life of couples in love on the pedestrian precinct by the sea. Each piece contains some very telling details. The Piast-period eagle symbols [i.e. dating to the beginnings of Poland as a state] on the military caps, ramshackle trucks and obelisks whose shadows embraces young people of the big-beat generation, giving one another a hug. This time, the line is quieter, not so frantic as it used to occur three years before in Łowicz. Forms, closed up with a contour, represent quietness ensuing from self-assurance. Sometimes fine, almost too ‘beautiful’ against the genre of reportage-in-drawings. For the first time did Dwurnik show what is a means, as opposed to what it a target, in his art. He became a virtuoso of drawing not for the sake of a purposeless show, but in order to even more freely play with forms being drawn directly from the environment. Whenever he can feel he has seized control of a technique, he dares dive into the reality even more willingly. No matter he cannot, as Picasso could, make portraits of personages in the rank of Cocteau or Stravinsky. Cannot a sergeant of the People’s Polish Army act with equal success as a model? A line would not care, would it, about whether to be put across a wise forehead of a Mr. Stravinsky, or a bullish neck of a military officer. Whether we get delighted with either, is rooted only in a whim of History. The whole ‘Kołobrzeg’ cycle shows that this time, the Author didn’t quite have to haste to catch a train or a passing vehicle. Instead, he could devote his whole lazy afternoons to chiselling these drawings, as his students were released from the (otherwise obligatory) making of painted propaganda slogan boards. A familiar climate of the venue was contained in the odours: musty humidity of the corridors got mixed with waves coming during meal-serving hours from the canteen. Dwurnik excelled in his masterful study series of the barracks’ ‘machinery park’. His imagination was then geared at an engineer’s level, the hand transferring objects of the artist’s fascination onto the sheet: once, a howitzer thrown by a fence, then, a rusted bulldozer, and then again, a machine gun rack. The indifferent mode of Dwurnik’s pencil is absolute. It may rival the cold terseness of David as he was making his sketch of Queen Marie Antoinette.

Klimontów, from the cycle ‘1’, watercolour, 23.5 x 35 cm, 1965.

Let’s now travel back, into the year 1965. Despite the faded colours and destroyed paper sheet, the watercolour ‘Fara w Klimontowie’ [The Parish Church at Klimontów] is charming with its simplicity, straightforwardness, and chastity. We are now looking at a piece by a twenty-two-year-old man. And we are willing to discover one of the secrets of Art, the mystery of a style taking shape. How deep into the past are we allowed to dive, not crossing the barrier of intimacy? Even the greatest artists have, somewhere, a borderline which we should not be allowed to pass. But at twenty-two, Dwurnik was already well on his just way. Moments after an illumination whose shine has remained by this very day in this one paper scrap. It is there that the hasty rhythm of architectural forms appeared. What was so important about his meeting with Nikifor at the Warsaw Fine Arts Academy yard? Is the story realistic at all, or is it but a myth which Dwurnik has used as a disguise for his admiration of the old artist?

Wzdłuż ulicy jadą żołnierze [Soldiers Going Along the Street], from the cycle ‘Miasta’ [Cities], watercolour, 33.5 x 48 cm, 1968.

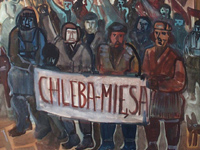

On March 8, 1968, Dwurnik, running away from police’s batons, run against a lamp post at Traugutta Street in Warsaw. The broken head got healed, whereas the street’s patron, Romuald Traugutt, became the character in several of the artist’s paintings. Militiamen (policemen of the time) were banned as art subject by the censorship, but quasi-operetta-style coarse soldiers riding their rocking horses aroused no suspicion. Those doll-like figures do not make one as frightened as a mug and a truncheon of a ZOMO [‘Mechanised Civil Militia Troops’] man, but that they have been introduced into the world of Polish small cities points out to a deeper anxiety with which Dwunik’s vision of the world and history is lined. Seemingly, the artist is particularly sensitive to a subcutaneous pulsation of anarchy. Over and over again, he shows minor or major eruptions of a revolt, various brawls, tumults, drunkards’ or sexual orgies. The omnipresence of violence, harm, and knocked-out teeth is a fact; one may not call it into question, nor turn his or her back on it. The only permitted action is self-protection against this madness. Matters just or unjust, random victims – owing their fate or not? Who on earth would dare resolve this question? Just in case, one would rather distance himself or herself from it, adding, to the demand slogan: ‘Give us bread!’, the phrase: ‘And meat!’ Apart from albums with Bernard Buffet painting, a trip to Paris may give you an opportunity to get yourself a Maoist uniform and cap.

When a fourteen-year-old Ed, a primary school student of Radzymin, prepared himself to entrance examination at a Visual Arts College, he practised drawing with a model for hours and hours at his home. The model was his own mother, Władysława Dwurnik. The boy must then have discovered for himself that being an artist is no joke: when doing this home exercise, the old woman happened to faint three times. Another of his models, and teachers too, Czesław Wdowiszewski, the famous painter, would fall asleep while made subject to similar trials on a regular basis. It was his wife Nina who, on presenting the aspiring young artists’ portfolios, was the first to shout out to the fourteen-year-old: ‘Ed, you did it!’ And so, Eddie took the drawings from his folders and deployed them on the representative stairs of the college. He started from the ground floor, disappeared on the first floor, passed by the second; past the third, there was an attic. The old ‘Warszawa’ automobile on which his father brought him from Radzymin for his examination, got its suspension spring broken on the way.