An I who is Another

In the West, a mirror is a totally narcissistic object: one thinks about it as a thing one is reflected in; in the East, though, a mirror seems empty; it is a symbol of the emptiness of symbols. A mirror only reflects other mirrors, and that endless reflection is emptiness (which, as we know, form is as well).

Roland Barthes1

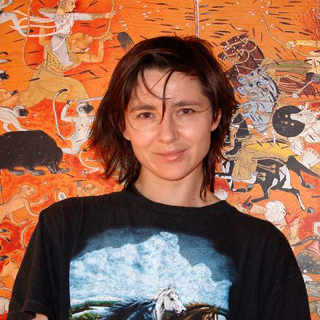

Photographs of a studio: paintings on the floor; small sizes arranged carelessly, supported against freshly grounded canvas or standing on the edge of a large stretcher with the canvas turned to the wall. Reverse and obverse, emptiness and meaning. Hasty stock-taking - is that not the purpose of photographing a studio? - reveals a certain repetitiveness of motifs: a galloping horse, two horses - usually red on a red background - nibbling grass or copulating... But, as Taro Amano says2, If we expect value in a photograph, we must look for it only in the relation between the photographer and the object. Perception includes also what consciousness pays no attention to. This refers to details both of the object itself and of its background, which escaped the photographer’s notice, but were seen by the camera - they also have a story to tell.

For example, red flip-flops on the floor, a fragment of a drawing - clipped by the edge of the photo - showing a sleeping figure, or the sun shining through the window onto the largest painting.

The photo also shows a young woman drawing busily. In accordance with the tradition of representing a painter’s studio, we tend to believe she is the artist. But her slanting eyes suggest that we are the victims of a deceptive and useless habit, caught in a net of delusion. In another photo another female figure (the same? different?) turns away from us to stare into a blazing sun in a painting and thus conceals her face. It is more a portrait of a painting than of a woman. We’re only allowed to see a contour of her face, the eyebrows, the eyelashes. A detail.

A supposed diary by the same artist, and author of the photos, Agnieszka Brzeżanska, published in a catalogue of her exhibition in 1997, was a similar fabrication. My friends are beginning to recognize my self-portraits. Only it’s themselves they recognize in them! I have painted myself again, and again someone else identified themselves.3 Let’s take a closer look at this sentence: it describes despair, the inability to construct identity, a face as emptiness. A self-portrait seen as a portrait of the Other. The individual refusing to be the universal. The myth of the Androgyne? No, rather a woman’s fear described by a man pretending to be a woman. An I who is Another.

A Japanese man imitating a woman remains within the boundaries of art and convention sanctioned by many centuries of long tradition. It began over a thousand years ago with diaries and short poems narrated in a feminine first person by men “imagining a woman’s feelings” in order to identify with the so-called “woman’s hand” and write using the more decorative kana characters, traditionally used by women. In the tradition of painting, which combines image and writing, the “feminine hand” was the equivalent of “feminine thinking.” A “masculine hand” also existed, which was used for writing Chinese characters and was strictly reserved for men. Like writers, they could also assume a feminine style. The division masculine-feminine was clearly discernible in painting subjects: Chinese (Kara-e) represented the external, the public and the masculine; Japanese (Yamato-e) - the private and feminine.4

In the earliest self-portrait - a pencil drawing - she is easy to recognize, leaning out from behind the edge of the paper. Her neck in the tight band of a polo neck - accident or stylization? women’s robes were finished like that in the nineteenth century. Tied hair, covered forehead, lips pressed tightly together, and eyes fixed on her own reflection. The stiff, upright posture and pursed lips may be signs of rebellion or refusal. In the mirror Agnieszka Brzezanska, who is yet to become a painter, sees a woman. “Men act,” writes John Berger5, women reveal themselves. Men look at women. Women look at themselves being looked at.

Further, he adds: A woman’s observer within herself is masculine, the observed - feminine. Thus a woman transforms herself into an object, particularly an object of seeing.

Faces. Obsession with faces. In the fictional diary from 1997 she wrote: I can’t feel them looking at me all the time yet... there’s something wrong with the eyes in all the portraits... they all have unseeing eyes, they seem to be looking inwards. Refusal to be present, for eyes betray an onlooker and a painter. In January: The end. Once I didn’t know how to paint eyes that could see. In January she recognized herself in a painting. One might hypothesise that those early self-portraits are ambiguous, revealing the painter to be caught between the opposing notions of being an artist and a woman, and constantly hesitating between the reluctance to be looked at and total submission to “being an object”. Her early linocut nudes resemble the works of artists from the beginning of the twentieth century, when images of a woman’s body functioned in art as signs of male sexuality and avant-garde affiliation

6. Lynda Nead, summarizing Carol Duncan’s views, states that “the submission of a woman’s body to stylistic deformation and formal abstraction in modernist art is a manifestation of women’s subordination in culture. They are treated as powerless, helpless beings, who can only be endowed with meaning by a masculine avant-gardist’s creative power and potency.”7

The female figure in the linocut “Dreamy Pink” seeks eye contact with us and submits to our gaze. The one in “Cowering” closes her body to us, immersed in thought, distant, not unlike the woman (another self-portrait?) from the later drawing “Follow your dreams”: she covers her eyes, separating herself from our gaze, and is literally lifted in her dreams. Fragmented human figures in “inventory pictures” - someone’s eyes, ears, hands (“Them”), profiles (“Left (and right”), mouth (“Dwoje” / “Two of Them”) shunning our desire for the whole. Incomplete, separate, though together.

When walking through a city it is easy to notice that the camera - the simplest, disposable type - has become an everyday object, a essential accessory of high-school girls. All kinds of automatic photo booths are popular in Japan; girls use them to have their pictures taken, which are immediately developed and printed on easily separated stickers.8

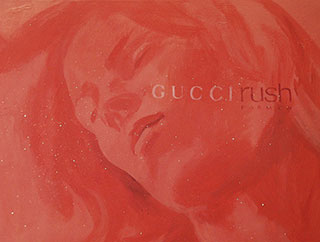

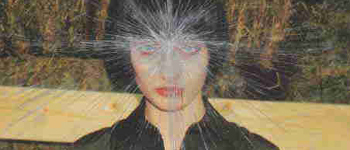

The photos of the studio were taken in Japan, where Agnieszka Brzeżanska has been living since 1997. She emigrated, as she says, in order not to waste time on habits. Not to stand in front of a mirror. In Japan she discovered photography. Usually she photographs herself. In pictures taken by others she disappears. Being a twofold object of observation - as a woman and as a stranger - she controls the extent of her visibility, scratching off the spots were she recognizes herself; the scraped enamel gleams. A similar scraping-off procedure, she says, is applied in Japan to pictures of pubic hair or women’s genitals in pornographic magazines. An invisible, and hence non-existent spot is the sign of a taboo.

The same trick is used with advertising photos. Adding (although she actually subtracts, removing the print) haloes around models’ heads she exposes the double meaning of the representations, their overtly sexual connotations within the iconographic schemes of religious painting (“Maiden with a lamb”, “Adoration”). In the most recent works, such as a brochure advertising a spring fashion collection, haloes around the models’ heads show the shots to be styled on Victorian Pre-Raphaelite paintings and reveal the model of femininity produced by mass culture.9

Her most recent self-portraits, done in Polaroid (their creation certainly accompanied by a fear of her own face dissolving in a sea of other signs, of losing her identity) can by interpreted in the context of mass culture as well: in casual, spontaneous snapshots she seems to be trying on various female identities: dreamer; sad; sleepy - she communicates a desire for the observing and the observed to be of feminine gender: women and women artists. Sometimes a single paper flower , a rose or a narcissus, blossoms from a photo to which it is pasted (flowers as metaphors of the female body in Nabuyoshi Araki’s photos are different). When there are more, she becomes unrecognizable. The symbolism of flowers is traditionally associated with femininity. A flower is a vulva, a woman’s love, but also passive submission the principle of passivity. In the artist’s photographic self-portraits they are the external, which reveals itself, but also a veil screening her from our eyes.

In Agnieszka Brzeżanska’s latest drawings, inspired by photos from Wong Kar Wai’s films, He and She appear, locked in a loving embrace. Beside them, on a sheet of paper, a Hindu flower ornament bursts into blossom - the same which women in India draw on their hands, and West European girls imitate using decalcomania. In Hindu tradition a flower symbolizes blessing: when Buddha spoke, flowers rained from heaven.

A horse - the archetypal symbol of male sexuality, a phallic symbol - painted by a woman, becomes her signature, the Red Mare, Saranyu, who - as in the latest picture Follow your dreams literally, not just in the imagination, reaches dreams and leaps at full gallop from one continent to another.

Notes and references

- 1. Roland Barthes, Imeprium znaków (The Emipre of Signs), Warsaw 1999

- 2. Taro Amano, Fotografia (Photography), in: Gendai. Wspólczesna sztuka Japonii. Pomiedzy cialem i przstrzenia. - exhibition catalogue, Warsaw 2000; p. 120

- 3. Tomasz Lipko in: Agnieszka Brzezanska, Wydrap mi oczy (Scratch Out My Eyes), exhibition catalogue, Poznan 1997; p. 151 All quotations form the artists “diary” come from that catalogue.

- 4. Maria Brewinska, Gendai: Wspólczesna sztuka Japonii. Pomiedzy cialem i przestrzenia, p. 55

- 5. John Berger, Ways of Seeing, Poznan 1997; p. 151

- 6. Lynda Nead, The female nude. Art, obscenity and sexuality; p. 82

- 7. ibidem

- 8. Taro Amano, op. cit., p.120

- 9. On the sources of the popularity of Pre-Raphaelite painting in mass culture see also Griselda Pollock, Woman as a sign: psychoanalytic readings, in: Vision & Difference. Feminity, Feminism and the Histories of Art; London/ New York 1994 (first edition ??)