Does Koza do it with dogs?

A gun aiming at a girl. A brunette in a red dress and slippers cocks her head flirtatiously and confesses: I was a rich man’s plaything

. The gun fires; a bubble comes out saying POP!

In 1947 in Paris Eduardo Polozzi used the cover of a glossy magazine to create the collage I was a Rich Man’s Plaything, combining a Coke advertisement with lurid titles: The Sinning Sister, The Street Walker, If it’s a sin…, I confess. The title of the original gutter magazine has been preserved. It reads: “Intimate Confessions”.

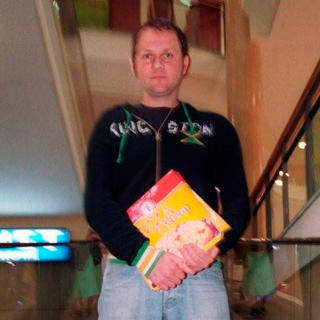

Sixty years later in a cafe in a big supermarket, I ask Janek Koza, who paints ketchup jars, makes paper models of hairspray cans and draws a cartoon entitled Erotic Confessions about pop-art. He washes his hands of it.

Post-polo-pop-art

Stole ten jars of ketchup from the store today

The week’s biggest loot and not a cent to pay

But the cops spotted him

Went at once after him

He hid the ketchup under his leather jacket

The cops will never track it.(from the poem Ten Jars of Ketchup by Janek Koza)

He doesn’t want to be the Wrocław Warhol. Even though, just like the king of pop-art in his youth, he works for an advertising agency (he moved to Warsaw three years ago) and, also like him, he is a young but popular graphic artist, illustrator and advertising specialist.

When asked about his sources of inspiration, Koza is not very eloquent. I finally manage to get this out of him:

‘You could say that Andy Warhol is, like, similar, because of the cans and stuff. But the thought behind my paintings is very different. I’m not saying he’s not good, although I rather prefer Jeff Koons’ (enormous dogs made of flowers, steel rabbits which look like inflatable toys, paintings and sculptures showing the artist having sex with his wife, the Italian porn star Ciocciolina – a mixture of kitsch, modernity and eroticism, very much to Koza’s taste.)

‘Well – I think that Warhol was thoughtless on principle’ Janek blurts out. ‘He avoided all thought, or you might say that the thought behind his paintings was thoughtlessness, whereas in mine there is reflection.’ At this point his confidence ebbs and he adds somewhat less briskly: ‘Well, that’s what I think, but I’m not an art critic or anything, just - in practice…’

‘Reflection?’ I press.

‘Yeah, sort of general.’

‘Reflecting that…?’

‘Well, as to that, I’d rather not say. I can’t, like, put it in a few words.’

Maybe the point is that when Koza paints four jars of ketchup he’s not only referring to Warhol’s cans of Campbell’s tomato soup; his painting is not just a comment on mass culture and the consumer society. When he paints the tomato on the label, he’s really interested in the tomato. When he paints a box with a cat on the lid, he’s interested in the cat. He is ironical – he makes witty references to art history: Sunny margarine is suggestive of Van Gogh, Positive and Negative bars of lard are a tribute to Mondrian. Tacky flowers, fruit and butterflies allude to the tradition of painting still life, and copies of mineral water labels – to landscape painting.

It comes as no surprize that sixty years after pop-art Koza wants to paint labels from foodstuffs. It is only now that Poland is experiencing real mass culture, rampant consumption, fully fledged commercials, a flood of talk-shows, in which Janek can find plenty of material for his erotic comics. If that’s not pop-art., I suggest the term post-polo-pop-art: Polish, post-modern, amusing.

When Koza paints Michael Jackson, he doesn’t just create an icon of a celebrity as Warhol did when painting Marilyn Monroe or Elvis; he juxtaposes Jackson’s portrait from the time when he was still black and one from the time when he was white with white sausage and black pudding. ‘It’s all a sort of a statement about, er… meat… and race…’ he explains haltingly.

Koza speaks little, but does a lot. He is a versatile artist, he can paint and draw and make a film and an installation too. He also writes beautiful poems about things and feelings.

Things and feelings

I bought you a plastic flower today, my love

It will last a thousand years

We will die

Then our children

Civilization will die too

Only waste will remain

But my flower will survive all

All storms and gales

For it’s a lasting value

Opposed to nature(1000 years by Janek Koza)

But it’s not for his paintings that Janek Koza is renowned. He owes his fame to erotic cartoons and films, in which he touches upon the delicate matter of feelings and desires, studies the economics of lust, listens in on our intimate erotic fantasies. The anatomy of love according to Janek Koza is a frightening science. It’s not without good cause that Paweł Jarodzki (painter, member of Luxus) warns on the back cover of the comic Erotic Confessions against the content, which can lead to nervous breakdown, disillusionment and frustration: ‘Leave this book! Save your innocent heart!’

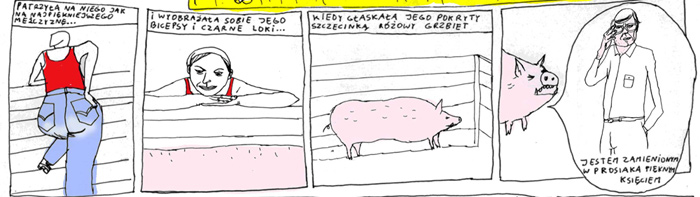

Inside, you will find complicated human relationships (and not only human, since it is possible to fall in love with a dog or a hog), bloody love scenarios, sad and cruel bedroom scenes, the world of dreams of low-level employees, with saggy breasts and big stomachs. Koza’s drawing emphasizes the pathetic quality of that world, where housewives dream of an affair with the plumber and girls of an ‘adventure’ with a disco-polo star.

Koza, as usual, is unhelpful as a source of information:

‘Where do you get those ideas from?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Do your friends have such fantasies?’

‘Dunno.’

‘Do you have any unusual erotic dreams?’

‘Oh, no. I’m very usual.’

‘Do you and your girlfriend bring bodybuilders home and use them as teddy bears, like in the cartoon?’

‘Well, as to that, we’ve got two dogs.’

‘Do they sleep with you?’

‘No, they’re not allowed to. We bring them up quite strictly.’

‘What kind of dogs are they?’

‘Mongrels. One’s big and white, the other small and black.’

‘Like the sausage and black pudding in your picture?’

‘Yeah, but that’s a coincidence.’

‘Janek, you’re not saying anything, how am I supposed to interview you?’

‘You can write something yourself and say I said it.’

One is tempted to roll out the heavy artillery of Julia Kristeva’s theory of ‘the abject’. One might study the content eliminated from the common consciousness, which Janek smuggles back on the pages of his cartoon and in his films. But it’s so much more fun to turn off the TV full of beautiful people, throw aside magazines featuring perfectly built women and read Erotic Confessions. What a relief.