The Art of Storytelling

“... but a foreigner, as soon as he arrives in an unknown city and casts a glimpse into that pine-cone of pagodas and lightshafts, and attics, tracing the zigzags of canals, vegetable gardens, rubbish heaps, will immediately distinguish ducal palaces, temples of great priests; he will recognize the inn, the prison, the thieves’ quarter. Thus, some will say, the hypothesis is confirmed that every man bears in his mind a city composed of differences only, a city without shape or figure, which is filled by particular cities.”

This passage comes from one of the fifty-five tales told to the Mongolian ruler of the world by Marco Polo in Italo Calvino’s book Invisible Cities. For many days the Venetian traveller tells, and the khan listens to, stories which ever again repeat the same plot, the same pattern, the same narrative structure. Yet the listener is not bored: tales - stories which are told, as opposed to those that are written down - are in fact innumerable variations of one tale “without shape or figure”, filled in by the particular story.

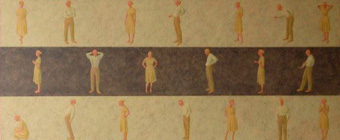

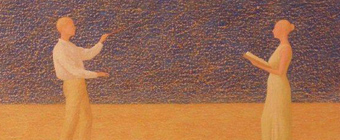

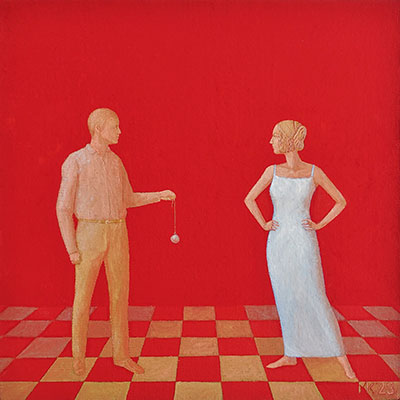

Mikolaj Kasprzyk’s paintings are notable for this kind of repetitive structure: two tiny humans with a Castle in the background, engaged in dialogue with each other and with the carpet of space in which they have been inscribed; several figures in expressive postures - stages of one activity broken up into single gestures; the silent dialogue of two figures standing facing each other and communicating through the position of their hands, arms and bodies, like dancers or mime artists. Throughout many paintings Kasprzyk continues his tale, a narrative not of a writer but of a storyteller. He does not appeal to the mode of artistic perception created by the literary culture of modern Europe, but to the pre-literary, oral tradition of storytelling, and this he translates into paintings. That is why his works have, for a contemporary audience, a pleasant flavour of something archaic, of a journey back to the sources, to a different understanding of art.

According to historians of culture, oral communication has certain very definite structural features. A tale transmitted by word of mouth is created by adding subsequent episodes; in contrast, a written story is organized from the start according to the pattern of “introduction - climax - denouement”. A tale does not have one climax, an the pleasure we derive from it does not rely on our curiosity being satisfied once, but on the possibility of endlessly adding new elements without risk of upsetting the structure. Is it not the same with Kasprzyk’s paintings? Doesn’t their attractiveness spring largely from lack of one centre of gravity? Even the Castles with their central structure sprout from a landscape overgrown with thousands of similar trees-episodes. And just as in a story each element added to the narrative has its beginning and its end, trees and people in Kasprzyk’s paintings are closed, clearly defined, independent forms, which can be added. Of course just like a good storyteller knows when to finish his tale, Kasprzyk controls the arrangement of episodes on his canvas.

The point of a tale lies in accumulating a large number of elements rather than in a detailed analysis of structures. Listening to a tale is a trance activity, based on participation, while a written and read story gives pleasure to an analytically minded observer. Repetitive, rhythmically and symmetrically arranged scenes-episodes favour such participating, “story-like” reception of Kasprzyk’s paintings.

Marco Polo, when telling Kublay-khan of distant - and maybe non-existent - cities, each time tried to create, for the listener’s benefit, something concrete, to give form to the “city without shape or figure”, fill it with described reality, describe its situation in space and time as well as in human desires and words. Marco Polo’s cities are no abstraction, even though it is not clear whether they exist beyond the imagined reality of the story. Similarly, Kasprzyk’s paintings rely on the specificity of form - clearly defined, recognizable and compact. The story does not aspire to abstract deliberations; the present, a situation, an incident are its domain. And that is its strength: creating convincing specific situations, linked by the hero’s person.

Mikolaj Kasprzyk can be seen as someone like an Oriental storyteller who changes the words of his story into pictures and thus attempts to create art which, while remaining faithful to its narrative character, is freed of the irritating ballast of literature. It is not Kasprzyk’s aim to reduce painting to its merely formal qualities, even though he appreciates their importance; he wants to preserve that which avant-garde movements have always questioned: the narrative. He does it by introducing the structure of pre-literary tales into his paintings - the structure well-known to anyone who has ever listened to another person’s confidences, to fairy tales or a friend’s reminiscences of an exotic holiday.