On The Revolutions of Colours

Abstract art has been one of the most characteristic cultural phenomena of the twentieth century. Its beginnings - historically quite young - date back to the distant epoch when Europe was just at the threshold of grand cultural changes, war cataclysms and bloody dictatorships. Insubstantial painting, however different in comparison to earlier phenomena, stemmed from a fertile ground of the Old Continent’s culture, simultaneously showing the faith in new better future. After years of existing it has somehow become - in the viewers’ conscience - a kind of classics, which can still irritate some people and some remain indifferent to it. Nowadays performance arts, installations and new media have overtaken abstract art. New canons have appeared even in painting. They were constructed in opposition to abstraction just like abstraction had been in opposition to substantial painting before.

Is there a point then in resurrecting something that was a novelty almost ninety years ago and now remains as a phenomenon described in history of art’s academic textbooks?

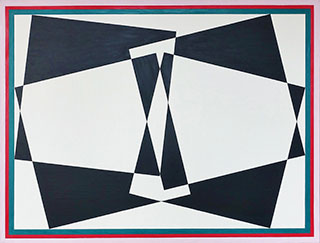

Małgorzata Jastrzębska attempts to do so. For two years she has been painting geometric abstracts based on precisely drawn composition and colour. The leading motifs of majority of her paintings are concentric circles composed of multicoloured segments, in which given hues overlap, and either contrast or harmonise with each other. The colours’ warmth defines the entire composition or a part of it. On the larger canvases there are combinations of circles, which colours overlap, interact with each other and cause an intriguing illusion of movement and dimension. In some of her works, the artist uses only chrome colouring of various tones, saturation and shades. She does not restrict herself to the palette of the visible light spectrum. Instead, she creates strong expressive combinations with black and white, which break through the chrome colouring and intensify the geometry of shapes, therefore making the composition more dynamic. On one of the canvases, the layout of black and white polygons constructs a running dimension, breached by divided composition and neighbouring intense colours. On the others, the tone and saturation of the colour or its warmth create a 3D show in front of the viewer’s eyes. Colour fields come together like an image in kaleidoscope (the painter admits her childhood fascination with this toy); however the chaos of scattered elements is soon overcome by a systematic central composition.

Jastrzębska’s works, regardless of their size, are oil on canvas. This conscious choice is dictated by her preference of technique. Instead of a title, each painting is given a sequential number (according to when it was created), which is logged in her study records. Every painting also has a start date, marking the beginning of the creative process. Time-consuming technique and complicated layouts require the work to be done in stages. The artist gets her inspiration from prior geometric sketches done both in her study and while travelling. There is no laborious copying of the study onto a canvas though; the sketches serve as inspiration helping the artist to create the final piece of art.

In the second decade of the twentieth century, multicoloured rotating circles appeared in the painting of abstractionists such as Robert Delauney, who based his work on Michel Eugène Chevreul’s theoretical research and establishment of the law of ‘simultaneous contrast’ of colours, i.e. the interaction of primary and complementary colours. Sonia Delaunay-Terk creatively approached the art represented by her husband and complemented the orphism canon (the name coined by Guillaume Apollinaire) with the cubic and fauvism experience. As an important figure in post war (WWII) art circles, she was co-creating Salon de Réalités Nouvelles. It promoted art that was developing the achievements of the interwar period. Małgorzata Jastrzębska conscientiously refers to Sonia Delaunay’s painting; nevertheless, she does not imitate her point-blank. She regards Cézanne, Mondrian, Strzemiński and Gierowski as her masters. Jastrzębska’s current works stem out from her love of abstract painting and the art of the first half of the twentieth century. Possibly, it results from her childhood and adolescence interests when mathematics (including geometry) and arts were her favourite subjects, or when a brief stint at the technical university enabled her to become acquainted with descriptive geometry. The artwork of this young artist is aware of the past but filtrated with modern sensitivity. Looking at the colourful shapes on the canvas, one can experience the pleasure of pure painting, which has always been the real power of abstraction.