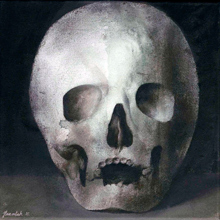

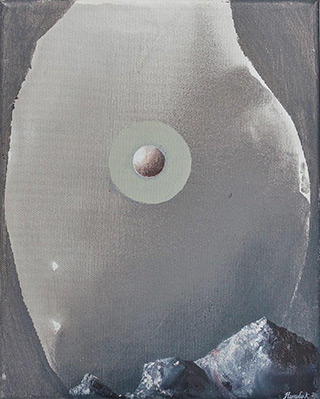

Greyness in the tone of Vanitas

In the meanwhile, there is no more radical a change than death. There is a reason why death is the most sublime refinement, the loftiest dignity, the most exquisite nobleness. Even a contemptible man after death is ennobled and should be spoken about with respect. It is not a coincidence that death is the teacher of aestheticism.

Alberto Savinio New Encyclopaedia

(translated by K. Brzozowski)

We wear it under our skin, which is plausibly the most fascinating phenomenon in these circumstances: we are a constant and continuously recurring, live symbol of our own transience, the closest and handiest exemplum of the situation. We never part with it, and if we eventually do, it means we cease to exist… Thus, as long as it is possible, we are better off not abandoning this most common symbol of our temporary transience. As long as we have it inside, we are not transient…

Skull motifs and skeletons did appear in Antiquity, though rarely – and initially as marginalia, as they do in modern art. There have been two points in the history of art that were their moments of sheer triumph. Never before or since has the skull been nestled and spread in art to such an extent as in the Middle Ages and the Baroque.

Most importantly, the skull lay at the foot of the cross on which Christ was killed. And since nothing happens by accident, it was there because, according to the divine plan, the location where the cross was erected by the Romans turned out to be, at the same time, the burial place of the first man/sinner – Adam, whose mortal sin Christ came to defeat. Therefore, the skull, present in so many medieval representations of the crucifixion at the foot of the cross, was the skull of Adam, whose mortality was defeated through the martyrdom of Christ, on the top of the hill called Golgotha, which means ‘the skull-pan of a head’.

Later, as the crowning of the skeleton, it decorated numerous dances of death, both written and painted, and most commonly carved in wooden blocks, immensely copied and duplicated, causing terror and despair among the living, to whom she was a constant reminder.

To this didacticism we owe another, exceptionally fascinating artistic phenomenon in Europe: cadaver tombs known as transi, which mainly took a sculptural form in the period of 200 years between mid 14th and 16th centuries. A man in transit, between life and death. To cut a long story short, it is a double-layer installation, combining what’s on the top of the tombstone: the deceased in his splendour, with his social status faithfully represented, with what’s hidden beneath: the earthly remains of the noble dead, consumed by decay and rot. Cadavers with remnants of skin, whose outflowing internal organs are eaten by snakes, lizards, frogs and toads, must have made an extremely unpleasant impression, since today it is not very different.

With time, the skull became more independent and prevailed in numerous representations, among which an important example of its expansion is the private 1485 triptych by Hans Memling, exhibited in the museum in Strasburg. The skull first appears next to the grave, left empty by a recently deceased man, only to become an independent theme on the other side of the triptych, proudly filling its space. It looks similar in the 1517 work by Jan Gossaert Mabuse, where it sits in the stone recess, with expressively broken jaw that emphatically emphasises impermanence. Soon afterwards, it appears in the 1521 drawing by Lucas van Leyden, portraying Saint Jerome, taking the whole foreground so unceremoniously and persistently that its presence is indisputable. Regardless of the settings in which the author of the first translation of the Bible into Latin is painted – in the deserts or in his study – the skull is usually present at the hand of this hermit and the greatest Biblicist of Christianity.

The skull is an equally common motif in the Italian Renaissance, both in painting and on medallions and reliefs. It is when it becomes an evident symbol of transience and impermanence of the world, a prop of old male and female hermits but, at the same time, it loses a greater part of its severity to the benefit of elegance. It is a regular companion of Mary Magdalene, where the allure of the naked female body is contrasted with the nakedness of the bone.

However, it was at the height of the Baroque when skulls became a popular theme of representations called vanitative, still-lifes of immense variety and currency, depicting musical and floral motifs, books, art and food; skulls could be found literally everywhere. One of the most recognised and typical representation is the work by Philip de Champaigne, the painter blending Jansenistic restraint with courtly splendour. The great portraitist and subtle colourist did not stop short of showing visible directness in the aforementioned still-life: he placed the polished skull on the stone table-top, between a small vase with a tulip and a sandglass. Thus, there is very little dilemma there – a choice between the quick trickling of sand and the slightly slower withering. In both cases, it is not difficult to predict the end, as it is always the same – the choice you make does not really matter…

The most ‘deadly’, however, were the paintings created in 17th century Spain, where artists seemed to have had no illusions whatsoever. The skulls by Antonio de Pereda, or the skeletons by Juan de Valdes Leal, could not positively predispose the audience to the predicted future: not only are we bound to pass away, but also life after death is very unlikely to bring us any joy – only suffering in Purgatory. The purpose of their works was to make sure the audience had no doubt about the pessimistic perspectives, and Iberian art gained this kind of bad reputation.

At that time, another painting strongly influenced the imagination of numerous painters, poets and writers, taking its place in the European culture. Under the influence of ancient writers, Guercino created a truly exceptional work of art: ‘Et in Arcadia ego’, where a group of shepherds find a skull in the middle of an idyllic landscape. The skull, however, is not what we are accustomed to seeing in other paintings – it is by no means elegant, sterile and picturesque – it is just hideous. You can still see traces of skin and hair, and a large menagerie, a fly, a mouse and a lizard, in its vicinity, hoping for a feast. It is not a symbol, not even a cemetery prop, but – on the contrary – a fresh finding, earthly and stinking in its nature.

The 18th century was not as interested in eternity as it was in fleeting moments. Vanitative contents in paintings did not disappear, but skulls were noticeably less frequent. At the end of the 19th century, it was Cézanne who returned to them and they also fascinated James Ensor, while in the 20th century the motif was present, on numerous occasions, in the works by Picasso and most recently in Gerhard Richter’s. A whole series was also created by Andy Warhol, who – apparently – considered them as saleable a product as any others.

Today, skulls are made of virtually everything: colourful beads, pills, crayon shavings, wax, sugar, chocolate, cigarette paper, glass, plastic, and – naturally – diamonds, just like the priceless jewel, the most famous skull of our times, the work by Damien Hirst. We find them on jumpers and in Swarovski’s jewellery. The pop cultural career of the skull and its trivialisation is a peculiar symbol of our times: deprived of mystery and its vanitative message, it has become part of unrefined decorative motifs. Certainly, this is not its ‘last word’, its final presence in art. Last year, during the Venice Biennale, the exquisite painter Marlene Dumas presented a series of skulls. The motif also appears in the melancholic cycles by Victor Man. And now they are joined by Łukasz Huculak, with a series of skulls so numerous and various as if he wanted to show that not only is the theme old and noble, but also inexhaustible. Or perhaps that the issue to which it refers is a kind of cultural obsession. The more it is hidden in the collective race for successful earthly existence, the more it can be heard in the individual subconscious.