An irrational joy of painting

Oh, so the world does exist after all. There is the market square in Lowicz and the parish church in Klimontów. Dabrówka exists, and even Warsaw, although I couldn’t imagine until now, exists too. And I thought everything had disappeared, I thought that we were back in the time before Creation, that there was no Krakowskie Przedmiescie, only an infinite black lake with chaos bubbling in it like tar. That only Big Brother’s house, an enormous tele-computer, was jutting out over the sea of emptiness, surrounded by millions of eyeless bodies. That we had all become an emanation of liquid crystal displays of the latest generation. That we’d sat down in front of computers and cancelled everything that was not a reflection, illusion, television.

As I think belief in the existence of the world is becoming increasingly rare, even among artists, who have also become hostages to computer-generated images, the slaves of artificial worlds duplicating themselves for a living - I can not resist the charm of Dwurnik’s drawings from the 1960s, showing little panoramas of Polish cities, towns and villages, and his watercolours, ageing slowly, like paper.

A pale computer screen in front of me. A TV set, the little pass to new-style salvation in the room next door. New eternity, new immortality. A remote control on a bedside table, like a headache or cough medicine in older days, ready to use. On the chair next to it a cellular phone is recharging. When it buzzes, I’ll run to the office to grind the unreality into which we have changed the world in newspapers, sacrificing so many innocent trees to illusion. The real pine tree will now be less real than the illusory, made-up fashion model on the cover. We have edited the whole world into a text, an what are we left with now? The affectation of looking, the pretence of an image.

It is only painters who look, see and believe the world exists in reality, not on a screen - such men as Nikifor or Dwurnik - that can save us now.

About a month ago on bus 106, which stops near the gallery, just past the Kultura cinema, I saw a girl. With her eyes fixed on a screen, leaning forward in her seat as if about to dive, she was clutching a blue mobile phone in both hands and pressing the buttons with the same devotion and determination with which her grandmother in a similar situation fingered the beads of a rosary. Detail: nails varnished light blue, doubtless to match the handset.

On Good Friday of 2001 a young boy traversed the market square in Lowicz, where I was waiting for my wife; earphones in his ears, sunglasses covering his eyes, who was he to himself? The hero of Matrix, the immortal Freddie Mercury? I think (and I wish I was wrong) that to him Lowicz, which Dwurnik had drawn with such attention to detail, did not exist. He was (we were there together) inside Tomb Raider, on a raid with the artificially beautiful Lara Croft. When he returns home, maybe to one of those lovely old tenement houses with windows overlooking the market square, he will plunge into a liquid crystal screen as into a modern paradise, and the market square will vanish. There will be no Lowicz, no Warsaw, no uneven pavements and paved streets ending suddenly in front of the frog-like bulk of the cathedral, which, albeit clumsily, does point beyond the horizon of your eyes.

All that will dissolve, and the waters of primaeval chaos will cover the little square in front of the cathedral; we’ll be back in the time before Creation, a miserable time. If you can not see heaven, you’re in hell. In the screen-hell you made for yourself.

This is the freedom of the immortal mind, perfectly replaceable bodies: Lara Croft shoots a guy, but in the next game he will come alive again to provide more cheerful cannon fodder. What the mind has forgotten, though, is the body it lives in. And that body really dies.

Instead of being God’s eyes, we have attempted to replace God. We have accelerated electrons so that they can generate images, and we have become, in a sense, self-sufficient. We have created everything anew in our image and after our likeness. Another pretence of escape from death, which exists, although the mind pretends it does not.

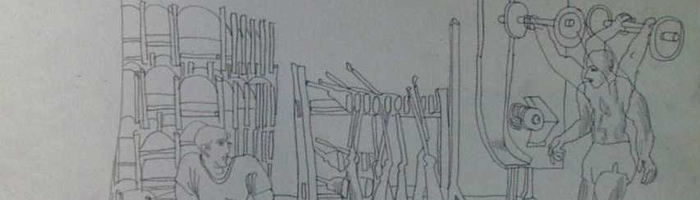

Differently from Dwurnik, who tried to see what is: the world we have already become estranged from. Hitch-hiking to Zloty Stok. Teresa at Kwiek’s. The Army gym in Kolobrzeg - grey, oppressive reality, simply seen and described. Admirable humility and a nearly forgotten kind of mastery: being an extension of what exists, of what was not created by us alone.

And, since I am becoming increasingly convinced that a painter’s only real calling is to be God’s eyes in this time when God has decided to retreat and hide, and to keep the world in existence for Him, I will repeat one more time that I like Dwurnik’s drawings. I like that passion: travelling from town to town, many hours spent over a sheet of paper repeating the same movements, almost meditation. I like that painting of anything on anything, without calculation or pose. When the hand is so tired that it forgets itself, it is led by the Something which is greater than us and which best testifies to its own existence.

There is pure looking without naming, without expectations, fears and hopes, on the edge where the painter ends and that which surpasses him begins (to paraphrase Czeslaw Milosz’s words). That which simply is. Dwurnik’s master, the great Nikifor, was such a God’s animal, sheer instinct, pure joy of looking and painting.

But, someone may argue, in Dwurnik’s watercolours, such as for example “Give us work, give us bread”, we do have that unnecessary naming, there is a placard, the devilry of politics and economy, and the colours are dun like fumes. It’s a corrupted world, not a divinely purified one. Such a world was the painters main subject for many years. We used to call it totalitarian, not fully understanding yet that reality is almost always blemished. Freedom has come, but has it freed anyone? Yet the market square in Lowicz still exists, and so does the joyous parish church in Klimontów.

Evil. What is a painter supposed to do with reality (political, economic, any kind), which, constantly and regardless of the system, either is hell or is slipping towards it? That corrupted reality touches Dwurnik and has always touched him, much more than it did Nikifor. After all Dwurnik is a painter who has been in the Centre for many years (and that, contrary to appearances, does not help), not God’s simpleton, a holy idiot, God’s animal.

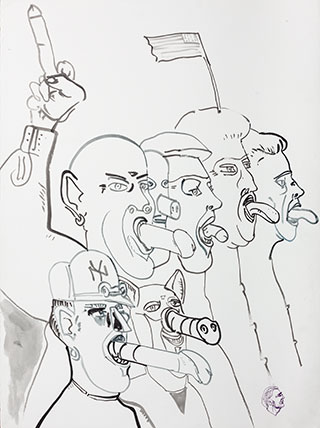

But if corruption exists, can we close our eyes to it and be satisfied with the purer tones, with pure harmony? Is there any other way than to see and paint that corruption? The only important thing is, to my mind, that the source from which the painting springs should remain pure. Dwurnik’s art is like that. His grotesque (lead or already plastic?) toy soldiers, although they radiate all the horror of the world, have so much naive, joyous childishness about them that one would like to play with them. And one notices, that Dwurnik also did that: he played. A child-painter, is that not the ultimate compliment?

We see the cheerful, irrational, improbable colouring of a prison. They are, obviously and possibly, also the colours of fear and insanity, but don’t they radiate some primaeval happiness? An irrational joy of painting, as in Van Gogh?

In this exhibition Dwurnik’s painter’s soul is faithful to the periphery; faithful to painting. And let it stay like that. For I believe that, contrary to all signs on earth, portending its disappearance, the future belongs to looking. To looking at the world, and not at its reflections in innumerable screens.